Kildin Sami

From a strictly geographical point of view, only Kildin and Ter, spoken on the Peninsula, could be regarded as Kola Sámi.

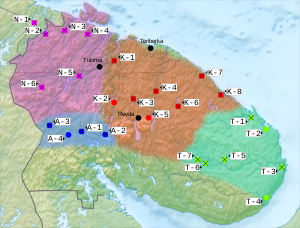

Originally, Kildin Sámi was spoken in clustered areas of the mainland and coastal parts of the Kola Peninsula.

[3] Nowadays, Kildin Sámi speakers can be found in rural and urban areas, including the administrative center of the oblast.

[4][2] Lovozero is known as the main place where the language is still spoken by 700–800 ethnic Sámi amongst a total village population of approximately 3,000.

[3] As a result of relocation, migration, and forced movement of the group, the community has really fragmented and become divided over other areas in Murmansk Region, thus leading to an inability for the revival and sustenance of their language, traditions, customs, and beliefs.

[6] In the Russian empire, the Kildin Sámi had no authority, rights or privileges, or liberties of autonomy and independence to control their affairs and to educate and teach their language through schools.

[8] His oppressive agricultural, economic, and cultural policies also led to the arrest of those who resisted collectivization, including many who lived in the Kola tundras.

[7] As Russia entered World War II, Kildin Sámi youth were drafted to serve in the Red Army, which lessened hardships and prejudices they faced for a temporary period.

[7] Although the repression ended after the death of Stalin in 1953, Russification policies continued and the work with the Sámi languages started again only in the beginning of the 1980s when new teaching materials and dictionaries were published.

[8] A majority of children remain ignorant of their traditional languages, customs and beliefs, and have had no formal or informal teaching which may give them a base of knowledge from which to work from.

[8] Although authorities and some government officials express a desire and willingness to resuscitate and revitalize the language, the community is not using that to their advantage, either because they do not know how to do so or whom to reach out to.

[8] Below is one analysis of the consonants in Kildin Sámi as given by The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages:[12] The Oxford Guide to the Uralic Languages gives the following inventory of monophthongs: Rimma Kuruch's dictionary presents a slightly different set of monophthongs: Kildin Sámi has been written in an extended version of Cyrillic since the 1980s.

The Sammallahti/Khvorostukhina dictionary (1991) uses Ҋ and ʼ (apostrophe); Antonova et al. (1985) uses Ј and Һ; a third orthographic variant, used by Kert (1986), has neither of these letters.

It was translated with the help of native speaker consultants, in Cyrillic orthography by the Finnish linguist Arvid Genetz, and printed at the expense of the British and Foreign Bible Society.