Kinetic art

Canvas paintings that extend the viewer's perspective of the artwork and incorporate multidimensional movement are the earliest examples of kinetic art.

[1] More pertinently speaking, kinetic art is a term that today most often refers to three-dimensional sculptures and figures such as mobiles that move naturally or are machine operated (see e.g. videos on this page of works of George Rickey and Uli Aschenborn).

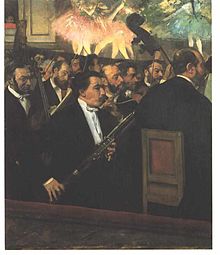

[4] During the late 19th century artists such as Degas felt the need to challenge the movement toward photography with vivid, cadenced landscapes and portraits.

Naum Gabo, one of the two artists attributed to naming this style, wrote frequently about his work as examples of "kinetic rhythm".

The strides made by artists to "lift the figures and scenery off the page and prove undeniably that art is not rigid" (Calder, 1954)[4] took significant innovations and changes in compositional style.

Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, and Claude Monet were the three artists of the 19th century that initiated those changes in the Impressionist movement.

In the same period, Auguste Rodin was an artist whose early works spoke in support of the developing kinetic movement in art.

However, Auguste Rodin's later criticisms of the movement indirectly challenged the abilities of Manet, Degas, and Monet, claiming that it is impossible to exactly capture a moment in time and give it the vitality that is seen in real life.

The lack of spacing is Manet's method of creating snapshot, near-invasive movement similar to his blurring of the foreground objects in Le Ballet Espagnol.

Degas' subjects are the epitome of the impressionist era; he finds great inspiration in images of ballet dancers and horse races.

In his 1860 piece Jeunes Spartiates s'exerçant à la lutte, he capitalizes on the classic impressionist nudes but expands on the overall concept.

In the 1870s, Degas continues this trend through his love of one-shot motion horse races in such works as Voiture aux Courses (1872).

Degas and Monet's style was very similar in one way: both of them based their artistic interpretation on a direct "retinal impression"[1] to create the feeling of variation and movement in their art.

He claimed that Monet and Degas' work created the illusion "that art captures life through good modeling and movement".

Sculpting put Rodin into a predicament that he felt no philosopher nor anyone could ever solve; how can artists impart movement and dramatic motions from works so solid as sculptures?

After this conundrum occurred to him, he published new articles that didn't attack men such as Manet, Monet, and Degas intentionally, but propagated his own theories that Impressionism is not about communicating movement but presenting it in static form.

Artists went beyond solely painting landscapes or historical events, and felt the need to delve into the mundane and the extreme to interpret new styles.

He wanted paintings, sculptures, and even the flat works of mid-19th-century artists to show how figures could impart on the viewer that there was great movement contained in a certain space.

When Jackson Pollock created many of his famous works, the United States was already at the forefront of the kinetic and popular art movements.

[citation needed] The novel styles and methods he used to create his most famous pieces earned him the spot in the 1950s as the unchallenged leader of kinetic painters, his work was associated with Action painting coined by art critic Harold Rosenberg in the 1950s.

[citation needed] In his Construction with Suspended Cube (1935–1936) he created a mobile sculpture that generally appears to have perfect symmetry, but once the viewer glances at it from a different angle, there are aspects of asymmetry.

For instance, kinetic-influenced mosaic pieces often use clear distinctions between bright and dark tiles, with three-dimensional shape, to create apparent shadows and movement.

It was a rhythm, much similar to the rhythmic styles of Pollock, that relied on the mathematical interlocking of planes that created a work freely suspended in air.

[citation needed] Tatlin's Tower or the project for the 'Monument to the Third International' (1919–20), was a design for a monumental kinetic architecture building that was never built.

[citation needed] Russian artist Alexander Rodchenko, Tatlin's friend and peer who insisted his work was complete, continued the study of suspended mobiles and created what he deemed to be "non-objectivism".

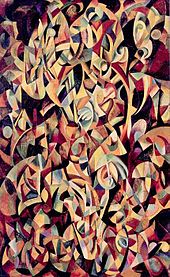

One of his canvas works titled Dance, an Objectless Composition (1915) embodies that desire to place items and shapes of different textures and materials together to create an image that drew in the viewer's focus.

[15][16] In 1955, for the exhibition Mouvements at the Denise René gallery in Paris, Victor Vasarely and Pontus Hulten promoted in their "Yellow manifesto" some new kinetic expressions based on optical and luminous phenomenon as well as painting illusionism.

The expression "kinetic art" in this modern form first appeared at the Museum für Gestaltung of Zürich in 1960, and found its major developments in the 1960s.

In November 2013, the MIT Museum opened 5000 Moving Parts, an exhibition of kinetic art, featuring the work of Arthur Ganson, Anne Lilly, Rafael Lozano-Hemmer, John Douglas Powers, and Takis.

[18] Changi Airport, Singapore has a curated collection of artworks including large-scale kinetic installations by international artists ART+COM and Christian Moeller.