Kinetoscope

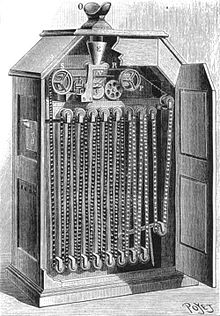

The Kinetoscope was not a movie projector, but it introduced the basic approach that would become the standard for all cinematic projection before the advent of video: it created the illusion of movement by conveying a strip of perforated film bearing sequential images over a light source with a high-speed shutter.

Dickson and his team at the Edison lab in New Jersey also devised the Kinetograph, an innovative motion picture camera with rapid intermittent, or stop-and-go, film movement, to photograph movies for in-house experiments and, eventually, commercial Kinetoscope presentations.

The completed version was publicly unveiled in Brooklyn two years later, and on April 14, 1894, the first commercial exhibition of motion pictures in history took place in New York City, using ten Kinetoscopes.

Instrumental to the birth of American movie culture, the Kinetoscope also had a major impact in Europe; its influence abroad was magnified by Edison's decision not to seek international patents on the device, facilitating numerous imitations of and improvements on the technology.

On February 25, 1888, in Orange, New Jersey, Muybridge gave a lecture amid a tour in which he demonstrated his zoopraxiscope, a device that projected sequential images drawn around the edge of a glass disc, producing the illusion of motion.

Around June 1889, the lab began working with sensitized celluloid sheets, supplied by John Carbutt, that could be wrapped around the cylinder, providing a far superior base for the recording of photographs.

[9] During his two months abroad, Edison visited with scientist-photographer Étienne-Jules Marey, who had devised a "chronophotographic gun"—the first portable motion picture camera—which used a strip of flexible film designed to capture sequential images at 12 frames per second.

[10] Upon his return to the United States, Edison filed another patent caveat, on November 2, which described a Kinetoscope based not just on a flexible filmstrip, but one in which the film was perforated to allow for its engagement by sprockets, making its mechanical conveyance much more smooth and reliable.

Its crucial innovation was to take advantage of the persistence of vision theory by using an intermittent light source to momentarily "freeze" the projection of each image; the goal was to facilitate the viewer's retention of many minutely different stages of a photographed activity, thus producing a highly effective illusion of constant motion.

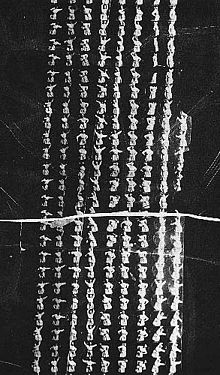

[15] As described by historian Marta Braun, Eastman's product was sufficiently strong, thin, and pliable to permit the intermittent movement of the film strip behind [a camera] lens at considerable speed and under great tension without tearing ... stimulat[ing] the almost immediate solution of the essential problems of cinematic invention.

"[26] Indeed, according to the Library of Congress archive, based on data from a study by historian Charles Musser, Dickson Greeting and at least two other films made with the Kinetograph in 1891 were shot at 30 frames per second or even slower.

[34] Evidently, that major redesign took place, as Robinson's description is confirmed by photographs of multiple Kinetoscope interiors, two among the holdings of The Henry Ford and one that appears in Hendricks's own book.

[42] Robinson, in contrast, argues that such "speculation" is "conclusively dismissed by an 1894 leaflet issued for the launching of the invention in London," which states, "the Kinetoscope was not perfected in time for the great Fair.

"[44] Noting that the fair featured up to two dozen Anschütz Schnellsehers—some or all of a peephole, not projection, variety—film historian Deac Rossell asserts that their presence "is the reason that so many historical sources were confused for so long.... [A]nyone who made a clear claim to see the Kinetoscope undoubtedly saw the Schnellseher under its deliberately deceptive name of The Electrical Wonder.

During the first week of January 1894, a five-second film starring an Edison technician was shot at the Black Maria; Fred Ott's Sneeze, as it is now widely known, was made expressly to produce a sequence of images for an article in Harper's magazine.

For the same amount, one could purchase a ticket to a major vaudeville theater; when America's first amusement park opened in Coney Island the following year, a 25-cent entrance fee covered admission to three rides, a performing sea lion show, and a dance hall.

[58] Even at the slowest of these rates, the running time would not have been enough to accommodate a satisfactory exchange of fisticuffs; 16 fps, as well, might have been thought to give too herky-jerky a visual effect for enjoyment of the sport.

[62] For a planned series of follow-up fights (of which the outcome of at least the first was fixed), the Lathams signed famous heavyweight James J. Corbett, stipulating that his image could not be recorded by any other Kinetoscope company—the first movie star contract.

According to one description of her live act, she "communicated an intense sexuality across the footlights that led male reporters to write long, exuberant columns about her performance"—articles that would later be reproduced in the Edison film catalog.

Along with the stir created by the Kinetoscope itself, this was one of the primary inspirations for the Lumière brothers, Antoine's sons, who would go on to develop not only improved motion picture cameras and film stock but also the first commercially successful movie projection system.

[75] An alternative view, however, used to be popular: The 1971 edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, for instance, claims that Edison "apparently thought so little of his invention that he failed to pay the $150 that would have granted him an international copyright [sic].

"[77] Given that Edison, as much a businessman as an inventor, spent approximately $24,000 on the system's development and went so far as to build a facility expressly for moviemaking before his U.S. patent was awarded, Rausch's interpretation is not widely shared by present-day scholars.

The October 1893 Scientific American report on the Chicago World's Fair suggests that a Kinetograph camera accompanied by a cylinder phonograph was presented there as a demonstration of the potential to simultaneously record image and sound.

"[84] While the surviving Dickson test involves live-recorded sound, certainly most, and probably all, of the films marketed for the Kinetophone were shot as silents, predominantly march or dance subjects; exhibitors could then choose from a variety of musical cylinders offering a rhythmic match.

[98] The Vitascope premiered in New York in April and met with swift success, but was just as quickly surpassed by the Cinématographe of the Lumières, which arrived in June with the backing of Benjamin F. Keith and his circuit of vaudeville theaters.

[100] In September 1896, the Mutoscope Company's projector, the Biograph, was released; better funded than its competitors and with superior image quality, by the end of the year it was allied with Keith and soon dominated the North American projection market.

[105] As far back as some of the early Eidoloscope screenings, exhibitors had occasionally shown films accompanied by phonographs playing appropriate, though very roughly timed, sound effects; in the style of the Kinetophone described above, rhythmically matching recordings were also made available for march and dance subjects.

Edison patented a synchronization system connecting a projector and a phonograph, located behind the screen, via an assembly of three rigid shafts—a vertical one descending from each device, joined by a third running horizontally the entire length of the theater, beneath the floor.

[109] It met with early acclaim, but poorly trained operators had trouble keeping picture in synchronization with sound and, like other sound-film systems of the era, the Kinetophone had not solved the issues of insufficient amplification and unpleasant audio quality.

Its drawing power as a novelty soon faded and when a fire at Edison's West Orange complex in December 1914 destroyed all of the company's Kinetophone image and sound masters, the system was abandoned.