War of the currents

In the spring of 1888, a media furor arose over electrical fatalities caused by pole-mounted high-voltage AC lines, attributed to the greed and callousness of the arc lighting companies that operated them.

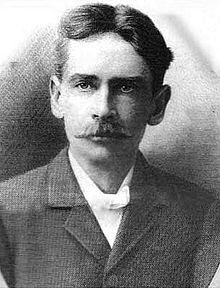

In June of that year Harold P. Brown, a New York electrical engineer, claimed the AC-based lighting companies were putting the public at risk using high-voltage systems installed in a slipshod manner.

In 1884 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania inventor and entrepreneur George Westinghouse entered the electric lighting business when he started to develop a DC system and hired William Stanley, Jr. to work on it.

To make matters worse for Edison, the Thomson-Houston Electric Company of Lynn, Massachusetts (another competitor offering AC- and DC-based systems) had built 22 power stations.

He also thought the idea of using AC lighting in residential homes was too dangerous and had the company hold back on that type of installation until a safer transformer could be developed.

[citation needed] As arc lighting systems spread, so did stories of how the high voltages involved were killing people, usually unwary linemen, a strange new phenomenon that seemed to instantaneously strike a victim dead.

[35] One such story in 1881 of a drunken dock worker dying after he grabbed a large electric dynamo led Buffalo, New York dentist Alfred P. Southwick to seek some application for the curious phenomenon.

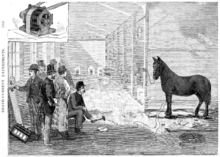

[36] He worked with local physician George E. Fell and the Buffalo ASPCA, electrocuting hundreds of stray dogs, to come up with a method to euthanize animals via electricity.

[24][45] At this point an electrical engineer named Harold P. Brown, who at that time seemed to have no connection to the Edison company,[47] sent a June 5, 1888 letter to the editor of the New York Post claiming the root of the problem was the alternating current (AC) system being used.

[58] In April 1888 Westinghouse engineer Oliver B. Shallenberger developed an induction meter that used a rotating magnetic field for measuring alternating current, giving the company a way to calculate how much electricity a customer used.

[62] The difficulties of obtaining funding for such a capital intensive business was becoming a serious problem for the company and 1890 saw the first of several attempts by investor J. P. Morgan to take over Westinghouse Electric.

The claims that AC was more deadly than DC and was the best current to use was questioned, with some committee members pointing out that Brown's experiments were not scientifically carried out and were on animals smaller than a human being.

[71] In order to more conclusively prove to the committee that AC was more deadly than DC, Brown contacted Edison Electric Light treasurer Francis S. Hastings to arrange the use of the West Orange laboratory.

[72] Based on these results the Medico-Legal Society's December meeting recommended the use of 1,000–1,500 volts of alternating current for executions and newspapers noted the AC used was half the voltage used in the power lines over the streets of American cities.

In March 1889 when members of the Medico-Legal Society embarked on another series of tests to work out the details of electrode composition and placement they turned to Brown for technical assistance.

[76] That spring Brown published "The Comparative Danger to Life of the Alternating and Continuous Electrical Current" detailing the animal experiments done at Edison's lab and claiming they showed AC was far deadlier than DC.

[77] This 61-page professionally printed booklet (possibly paid for by the Edison company) was sent to government officials, newspapers, and businessmen in towns with populations greater than 5,000 inhabitants.

[80] During fact-finding hearings held around the state beginning on July 9 in New York City, Cockran used his considerable skills as a cross-examiner and orator to attack Brown, Edison, and their supporters.

His strategy was to show that Brown had falsified his test on the killing power of AC and to prove that electricity would not cause certain death and simply lead to torturing the condemned.

[82] Newspapers noted the often contradictory testimony was raising public doubts about the electrocution law but after Edison took the stand many accepted assurances from the "wizard of Menlo Park" that 1,000 volts of AC would easily kill any man.

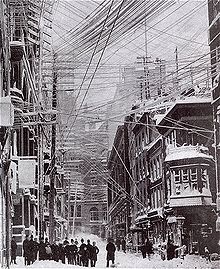

[24] On October 11, 1889, John Feeks, a Western Union lineman, was high up in the tangle of overhead electrical wires working on what were supposed to be low-voltage telegraph lines in a busy Manhattan district.

Feeks was killed almost instantly, his body falling into the tangle of wire, sparking, burning, and smoldering for the better part of an hour while a horrified crowd of thousands gathered below.

[89] Newspapers joined into the public outcry following Feeks' death, pointing out men's lives "were cheaper to this monopoly than insulated wires" and calling for the executives of AC companies to be charged with manslaughter.

"[90] Harold Brown's reputation was rehabilitated almost overnight with newspapers and magazines seeking his opinion and reporters following him around New York City where he measured how much current was leaking from AC power lines.

[93] The electric companies involved obtained an injunction preventing their lines from being cut down immediately but shut down most of their lighting until the situation was settled, plunging many New York streets into darkness.

[3][95] Edison hated the idea and tried to hold it off, but Villard thought his company, now winning its incandescent light patent lawsuits in the courts, was in a position to dictate the terms of any merger.

[97] Edison put on a brave face, noting to the media how his stock had gained value in the deal, but privately he was bitter that his company and all of his patents had been turned over to the competition.

New York City's electric utility company, Consolidated Edison, continued to supply direct current to customers who had adopted it early in the twentieth century, mainly for elevators.

New York City's Broadway theaters continued to use DC services until 1975, requiring the use of outmoded manual resistance dimmer boards operated by several stagehands.

[103] This practice ended when the musical A Chorus Line introduced computerized lighting control and thyristor (SCR) dimmers to Broadway, and New York theaters were finally converted to AC.