King Arthur

[7] The legendary Arthur developed as a figure of international interest largely through the popularity of Geoffrey of Monmouth's fanciful and imaginative 12th-century Historia Regum Britanniae (History of the Kings of Britain).

The 12th-century French writer Chrétien de Troyes, who added Lancelot and the Holy Grail to the story, began the genre of Arthurian romance that became a significant strand of medieval literature.

[a] Andrew Breeze argues that Arthur was a historical character who fought other Britons in the area of the future border between England and Scotland, and claims to have identified the locations of his battles as well as the place and date of his death (in the context of the extreme weather events of 535–536),[27] but his conclusions are disputed.

[30] Several historical figures have been proposed as the basis for Arthur, ranging from Lucius Artorius Castus, a Roman officer who served in Britain in the 2nd or 3rd century,[31] to sub-Roman British rulers such as Riotamus,[32] Ambrosius Aurelianus,[33] and the Welsh kings Owain Ddantgwyn,[34] Enniaun Girt,[35] and Athrwys ap Meurig.

[39] Linguist Stephan Zimmer suggests Artorius possibly had a Celtic origin, being a Latinization of a hypothetical name *Artorījos, in turn derived from an older patronym *Arto-rīg-ios, meaning "son of the bear/warrior-king".

[41] Another commonly proposed derivation of Arthur from Welsh arth "bear" + (g)wr "man" (earlier *Arto-uiros in Brittonic) is not accepted by modern scholars for phonological and orthographic reasons.

[42] An alternative theory, which has gained only limited acceptance among professional scholars, derives the name Arthur from Arcturus, the brightest star in the constellation Boötes, near Ursa Major or the Great Bear.

[43] Classical Latin Arcturus would also have become Art(h)ur when borrowed into Welsh, and its brightness and position in the sky led people to regard it as the "guardian of the bear" (which is the meaning of the name in Ancient Greek) and the "leader" of the other stars in Boötes.

"[49] The "Miracles of St. Mary of Laon" (De miraculis sanctae Mariae Laudunensis), written by a French cleric and chronicler named Hériman of Tournai about 1145, but referring to events occurring in 1113, mentions the Breton and Cornish belief that Arthur still lived.

Whereas numerous scholars have argued that this could have been due to the Abbey wanting to stand out with an illustrious tomb,[51] or to a desire of the Plantagenet regime to put an end to a legendary rival figure who inspired tenacious Celtic opposition to their rule,[52] it may also have been motivated by how the Arthurian expectations were highly problematic to contemporary Christianity.

[55] After the 1191 discovery of his alleged tomb, Arthur became more of a figure of folk legends, found sleeping in various remove caves all over Britain and some other places, and at times, roaming the night as a spectre, like in the Wild Hunt.

[79] Finally, Geoffrey borrowed many of the names for Arthur's possessions, close family, and companions from the pre-Galfridian Welsh tradition, including Kaius (Cei), Beduerus (Bedwyr), Guenhuuara (Gwenhwyfar), Uther (Uthyr) and perhaps also Caliburnus (Caledfwlch), the latter becoming Excalibur in subsequent Arthurian tales.

[87] The Welsh prose tale Culhwch and Olwen (latter half of the 12th century[88]), included in the modern Mabinogion collection, has a much longer list of more than 200 of Arthur's men, though Cei and Bedwyr again take a central place.

The story as a whole tells of Arthur helping his kinsman Culhwch win the hand of Olwen, daughter of Ysbaddaden Chief-Giant, by completing a series of apparently impossible tasks, including the hunt for the great semi-divine boar Twrch Trwyth.

[90] While it is not clear from the Historia Brittonum and the Annales Cambriae that Arthur was even considered a king, by the time Culhwch and Olwen and the Triads were written he had become Penteyrnedd yr Ynys hon, "Chief of the Lords of this Island", the overlord of Wales, Cornwall and the North.

In both the earliest materials and Geoffrey he is a great and ferocious warrior, who laughs as he personally slaughters witches and giants and takes a leading role in all military campaigns,[97] whereas in the continental romances he becomes the roi fainéant, the "do-nothing king", whose "inactivity and acquiescence constituted a central flaw in his otherwise ideal society".

So, he simply turns pale and silent when he learns of Lancelot's affair with Guinevere in the Mort Artu, whilst in Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, he is unable to stay awake after a feast and has to retire for a nap.

Perceval, although unfinished, was particularly popular: four separate continuations of the poem appeared over the next half century, with the notion of the Grail and its quest being developed by other writers such as Robert de Boron, a fact that helped accelerate the decline of Arthur in continental romance.

[112] This series of texts was quickly followed by the Post-Vulgate Cycle (c. 1230–40), of which the Suite du Merlin is a part, which greatly reduced the importance of Lancelot's affair with Guinevere but continued to sideline Arthur, and to focus more on the Grail quest.

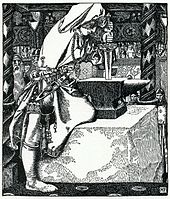

[113] The development of the medieval Arthurian cycle and the character of the "Arthur of romance" culminated in Le Morte d'Arthur, Thomas Malory's retelling of the entire legend in a single work in English in the late 15th century.

Malory based his book—originally titled The Whole Book of King Arthur and of His Noble Knights of the Round Table—on the various previous romance versions, in particular the Vulgate Cycle, and appears to have aimed at creating a comprehensive and authoritative collection of Arthurian stories.

So, for example, the 16th-century humanist scholar Polydore Vergil famously rejected the claim that Arthur was the ruler of a post-Roman empire, found throughout the post-Galfridian medieval "chronicle tradition", to the horror of Welsh and English antiquarians.

[116] Social changes associated with the end of the medieval period and the Renaissance also conspired to rob the character of Arthur and his associated legend of some of their power to enthrall audiences, with the result that 1634 saw the last printing of Malory's Le Morte d'Arthur for nearly 200 years.

[124] Tennyson's works prompted a large number of imitators, generated considerable public interest in the legends of Arthur and the character himself, and brought Malory's tales to a wider audience.

While Tom maintained his small stature and remained a figure of comic relief, his story now included more elements from the medieval Arthurian romances and Arthur is treated more seriously and historically in these new versions.

By the end of the 19th century, it was confined mainly to Pre-Raphaelite imitators,[131] and it could not avoid being affected by World War I, which damaged the reputation of chivalry and thus interest in its medieval manifestations and Arthur as chivalric role model.

[137] In John Cowper Powys's Porius: A Romance of the Dark Ages (1951), set in Wales in 499, just prior to the Saxon invasion, Arthur, the Emperor of Britain, is only a minor character, whereas Myrddin (Merlin) and Nineue, Tennyson's Vivien, are major figures.

The romance tradition of Arthur is particularly evident and in critically respected films like Robert Bresson's Lancelot du Lac (1974), Éric Rohmer's Perceval le Gallois (1978) and John Boorman's Excalibur (1981); it is also the main source of the material used in the Arthurian spoof Monty Python and the Holy Grail (1975).

As Taylor and Brewer have noted, this return to the medieval "chronicle tradition" of Geoffrey of Monmouth and the Historia Brittonum is a recent trend which became dominant in Arthurian literature in the years following the outbreak of the Second World War, when Arthur's legendary resistance to Germanic enemies struck a chord in Britain.

Lacy has observed, "The popular notion of Arthur appears to be limited, not surprisingly, to a few motifs and names, but there can be no doubt of the extent to which a legend born many centuries ago is profoundly embedded in modern culture at every level.