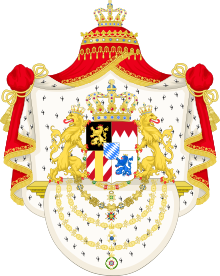

Ludwig III of Bavaria

As a result of this revolution, the Bavarian throne was abolished along with the other monarchies of the German states, ending the House of Wittelsbach's 738-year reign over Bavaria.

Ludwig was born in Munich, the eldest son of Luitpold, Prince Regent of Bavaria and of his wife, Archduchess Auguste Ferdinande of Austria (daughter of Leopold II, Grand Duke of Tuscany).

In 1861 at the age of sixteen, Ludwig began his military career when his uncle, King Maximilian II of Bavaria, gave him a commission as a lieutenant in the 6th Jägerbattalion.

In June 1867, Ludwig visited Vienna to attend the funeral of his cousin, Archduchess Mathilda of Austria (daughter of his father's sister Princess Hildegard of Bavaria).

He required that as part of the marriage agreement Ludwig renounce his rights to the throne of Greece, and so ensure that his children would be raised Roman Catholic.

Consequently, Ludwig's younger brother Leopold technically succeeded upon their father's death to the rights of the deposed Otto I, King of Greece.

They had a happy and devoted marriage which resulted in 13 children: On the death of her uncle Francis in 1875, Maria Theresa inherited his Jacobite claim to the thrones of England, Ireland and Scotland, and is called either Queen Mary IV and III or Queen Mary III by Jacobites.

As a prince of the royal house he was automatically a member of the Senate of the Bavarian legislature; there he was a great supporter of the direct right to vote.

The constitutional amendment of 1913 brought a determining break in the continuity of the king's rule in the opinion of historians, particularly as this change had been granted by the Landtag as a House of Representatives.

Later Ludwig even claimed annexations for Bavaria (Alsace and the city of Antwerp in Belgium, to receive an access to the sea).

A spurious story holds that, a day or two after Germany's declaration of war,[1] Ludwig received a petition from a 25-year-old Austrian, asking for permission to join the Bavarian Army.

Historian Ian Kershaw holds that Hitler's story is simply not credible on its face, due to the remarkable bureaucratic effort it would have required to attend to this minor matter during days of extreme crisis.

Already discussed since September 1917, on 2 November 1918, an extensive constitutional reform was established by an agreement between the royal government and all parliamentary groups, which, among other things, envisaged the introduction of proportional representation.

For the first time on 3 November 1918, initiated by the USPD, a thousand people gathered to protest on the Theresienwiese for peace and demanded the release of detained leaders.

On 7 November 1918, Ludwig fled from the Residenz Palace in Munich with his family and took up residence in Schloss Anif, near Salzburg, for what he hoped would be a temporary stay.

On 12 November 1918, a day after the Armistice, Prime Minister Dandl went to Schloss Anif to see the king in hopes of persuading him to abdicate.

The declaration was published by the newly formed republican government of Kurt Eisner when Dandl returned to Munich the next day.

Although the word "abdication" never appeared in the document, Eisner's government interpreted it as such and added a statement that Ludwig and his family were welcome to return to Bavaria as private citizens as long as they did not act against the "people's state."

In February 1919, Eisner was assassinated; fearing that he might be the victim of a counter-assassination, Ludwig fled to Hungary, later moving on to Liechtenstein and Switzerland.

In spite of fears a state funeral might spark a move to restore the monarchy, the pair were honored with one in front of the royal family, Bavarian government, military personnel, and an estimated 100,000 spectators.

Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber, Archbishop of Munich, in his funeral speech, made a clear commitment to the monarchy while Rupprecht only declared that he had stepped into his birthright.