Kingdom of Alba

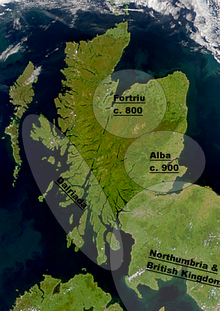

Alba included Dalriada, but initially excluded large parts of the present-day Scottish Lowlands, which were then divided between Strathclyde and Northumbria as far north as the Firth of Forth.

This differs markedly from the period of the House of Stuart, beginning in 1371, in which the ruling classes of the kingdom mostly spoke Middle English, which later evolved into and came to be called Lowland Scots.

English-speaking scholars adapted the Gaelic name for Scotland to apply to a particular political period in Scottish history, during the High Middle Ages.

[2] Some of the offices were Gaelic in origin, such as the Hostarius (later Usher or "Doorward"), the man in charge of the royal bodyguard, and the rannaire, the Gaelic-speaking member of the court whose job was to divide the food.

Constantine is credited in later tradition as the man who, with Bishop Ceallach of St. Andrews, brought the Catholic Church in Scotland into conformity with that of the larger Gaelic world, although it is not known exactly what this means.

Some time in the reign of King Indulf (Idulb mac Causantín) (954–62), the Scots captured the fortress called oppidum Eden, i.e. almost certainly Edinburgh.

King Kenneth II (Cionaodh Mac Maol Chaluim) (971–95) began his reign by invading Britannia (possibly Strathclyde), perhaps as an early assertion of his authority, and perhaps also as a traditional Gaelic crechríghe (lit.

In some respects, the reign of King Malcolm III (Maol Caluim Mac Donnchaidh) prefigured the changes which took place in the reigns of the French-speaking kings David I and William I, although native reaction to the manner of Duncan II's (Donnchad mac Máel Coluim) accession perhaps put these changes back somewhat.

Duncan had only been related to previous rulers through his mother Bethoc, daughter of Malcolm II, who had married Crínán, the lay abbot of Dunkeld (and probably Mormaer of Atholl too).

At a location called Bothganowan (or Bothgowan, Bothgofnane, Bothgofuane, meaning "Blacksmith's Hut" in old Gaelic,[9] today Pitgaveny near Elgin), the Mormaer of Moray, Macbeth defeated and killed Duncan, and took the kingship for himself.

It was Malcolm III who acquired the nickname (as did his successors) "Canmore" (Ceann Mór, "Great Chief"), and not his father Duncan, who did more to create the successful dynasty which ruled Scotland for the following two centuries.

The invasion got as far as Falkirk, on the boundary between Scotland-proper and Lothian, and Malcolm submitted to the authority of the king, giving his oldest son Duncan as a hostage.

In the ensuing conflict, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that: Donnchadh went to Scotland with what aid he could get of the English and French, and deprived his kinsman Domhnall of the Kingdom, and was received as King.

Anglo-Norman policy worked, because thereafter all kings of Scotland succeeded, not without opposition of course, under a system very closely corresponding with the primogeniture that operated in the French-speaking world.

The former's most notable act was to send a camel (or perhaps an elephant) to his fellow Gael Muircheartach Ua Briain, High King of Ireland.

The important changes which did occur include the extensive establishment of burghs (see section), in many respects Scotland's first urban institutions; the feudalisation, or more accurately, the Francization of aristocratic martial, social and inheritance customs; the de-Scotticisation of ecclesiastical institutions; the imposition of royal authority over most of modern Scotland; and the drastic drift at the top level from traditional Gaelic culture, so that after David I, the Kingship of the Scots resembled more closely the kingship of the French and English, than it did the lordship of any large-scale Gaelic kingdom in Ireland.

For when they learned of the King's capture the barbarians at first were stunned, and desisted from spoil; and presently, as if driven by furies, the sword which they had taken up against their enemy and which was now drunken with innocent blood they turned against their own army.

On the occasion therefore of this opportunity the Scots declared their hatred against them, innate, though masked through fear of the king; and as many as they fell upon they slew, the rest who could escape fleeing back to the royal castles.Walter Bower, writing a few centuries later albeit, wrote about the same event: At that time after the capture of their king, the Scots together with the Galwegians, in the mutual slaughter that took place, killed their English and French compatriots without mercy or pity, making frequent attacks on them.

[citation needed] The latter claimed descent from king Donnchadh II, through his son William, and rebelled for no less a reason than the Scottish throne itself.

This was how the Lanercost Chronicle relates the fate of this last MacWilliam: The same Mac-William's daughter, who had not long left her mother's womb, innocent as she was, was put to death, in the burgh of Forfar, in view of the market place, after a proclamation by the public crier.

[16]Many of these resistors collaborated, and drew support not just in the peripheral Gaelic regions of Galloway, Moray, Ross and Argyll, but also from eastern "Scotland-proper", Ireland and Mann.

The Scottish king was able to draw on the support of Alan, Lord of Galloway, the master of the Irish Sea region, and was able to make use of the Galwegian ruler's enormous fleet of ships.

Cumulatively, by the reign of Alexander III, the Scots were in a strong position to annexe the remainder of the western seaboard, which they did in 1266, with the Treaty of Perth.

The conquest of the west, the creation of the Mormaerdom of Carrick in 1186 and the absorption of the Lordship of Galloway after the Galwegian revolt of 1135 meant that the number and proportion of Gaelic speakers under the rule of the Scottish king actually increased, and perhaps even doubled, in the so-called Norman period.