Kingdom of Tungning

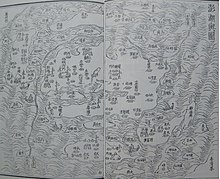

Under Zheng rule, Taiwan underwent a process of sinicization in an effort to consolidate the last stronghold of Han Chinese resistance against the invading Manchus.

In 1664, his son and successor Zheng Jing renamed it Tungning (Chinese: 東寧; pinyin: Dōngníng; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Tang-lêng, literally "Eastern Pacification").

Chenggong spent the first seven years of his life in Japan with his mother, Tagawa Matsu, and then went to school in Fujian, obtaining a county-level licentiate at the age of 15.

[16] After Beijing fell in 1644 to rebels, Chenggong and his followers declared their loyalty to the Ming dynasty and he was bestowed the title Guoxingye, or Lord of the Imperial surname, pronounced "Kok seng ia" in southern Fujianese, from which Koxinga is derived.

Qing reinforcements arrived and broke Chenggong's army, forcing them to retreat to Xiamen with many of the veterans and thousands of soldiers killed or captured.

To raise funds for his war effort, Zheng had increased foreign trade by sending junks to Japan, Tonkin, Cambodia, Palembang, and Malaka.

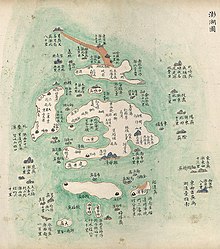

On 23 March 1661, Zheng's forces set sail from Kinmen (Quemoy) with a large fleet of 400 ships carrying around 25,000 soldiers and sailors aboard.

[22] Three Dutch ships attacked the Chinese junks and destroyed several until their main warship, the Hector, exploded due to a cannon firing near its gunpowder supply.

[27][28] In January 1662, a German sergeant named Hans Jurgen Radis defected and informed the Zheng forces of a weakness in the fort's defenses.

Zheng declared his intention to conquer the Philippines in retaliation for the Spanish mistreatment of the Chinese settlers there, which was also the reason he used for attacking Dutch Taiwan.

One version of events say he died in a fit of madness when his officers refused his orders to execute his son, Zheng Jing, who had an affair with his wet nurse and conceived a child with her.

[44] Realizing that defeating the Qing would not happen in the short term, Zheng Chenggong began transforming Taiwan into a temporary but practical seat of power for the Southern Ming loyalist movement.

[57] Aside from agricultural development, Zheng Jing advised commoners to replace their grass huts with houses made of wood and baked tiles.

[63] To address the food shortage, Zheng Chenggong instituted a tuntian (military farm) policy in which soldiers worked as farmers when not assigned to active duty in a guard battalion.

[64] Lands held by the Dutch were immediately reclaimed and ownership distributed amongst Zheng's trusted staff and relatives to be rented out to peasant farmers, whilst properly developing other farmlands in the south.

[64] According to Xing Hang, Zheng Jing dispatched teachers to various indigenous tribes to provide them with animals, tools, and know how on advanced and intensive farming techniques - severely punishing those that refused.

[66] Extensive farming spread Han Chinese settlements to the southern tip of the island and as far north as modern Hsinchu, often at the expense of aboriginal tribes.

[69] Chen Yonghua is credited with the introduction of new agricultural techniques such as water-storage for annual dry periods, the deliberate cultivation of sugarcane as a cash crop for trade with the Europeans, and the cooperative unit machinery for mass refining of sugar.

Zheng Taiwan held a monopoly on certain commodities such as sugarcane and deer skin, extracted from the aboriginals through a quota tribute system, which sold at a high price in Japan.

[70][45] Unlike the VOC, under which almost 90 percent of levies were related to commercial activities, there was greater emphasis on the rapid production of grains such as rice and yam to meet basic subsistence needs.

However the Zheng economy achieved greater economic diversification than the profit-driven Dutch colony and cultivated more types of grain, vegetables, fruits, and seafood.

In 1663, the writer Xia Lin who lived in Xiamen testified that the Zhengs were short on supplies and the people suffered tremendous hardship due to the Qing sea ban (haijin) policy.

[74] Due to the sea ban policy, which saw the relocation of all southern coastal towns and ports that had been subject to Zheng raids, migration occurred from these areas to Taiwan.

[45] From June to August 1663, Duke Huang Wu of Haicheng and commander Shi Lang of Tongan urged the Qing court to take Xiamen, and made plans for an attack in October.

[77][78] However, English trade with Taiwan was limited due to the Zheng monopoly on sugarcane and deer hides as well as the inability of the EIC to match the price of East Asian goods for resale.

Zheng emphasized that Taiwan had never been part of China and that he wished to establish relations with the Qing based on a model similar to a foreign country.

[80][45] After the military conflict with Zheng during the Three Feudatories revolt, the Kangxi Emperor made clear that he considered all the southern Fujianese living in Taiwan to be Chinese, unlike the Koreans, and that they must shave their heads.

[89] Shi Lang was instructed to arrange the necessary ships, escorts, and provisions for a peace mission to Taiwan, but he did not believe Zheng Jing would accept the Qing's terms.

Following an exchange of gunfire, the Qing were forced to retreat with two Zheng naval commanders, Qiu Hui and Jiang Sheng, in pursuit.

[103] Zheng Keshuang was taken to Beijing, where he was ennobled by the Qing emperor as Duke of Hanjun (漢軍公); together with his family and leading officers, he was also inducted into the Eight Banners military system.