Kinkaid Act

§ 224) is a U.S. statute that amended the 1862 Homestead Act so that one section (1 mi2, 2.6 km2, 640 acres) of public domain land could be acquired free of charge, apart from a modest filing fee.

[1] The act was introduced by Moses Kinkaid, Nebraska's 6th congressional district representative, was signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt on April 28, 1904 and went into effect on June 28 of that year.

[5] Only non-irrigable lands were eligible to be claimed under the provisions of the Kinkaid Act; those that were deemed to be practicably irrigable by the Secretary of the Interior were excluded.

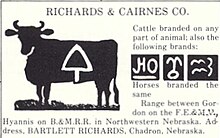

[8] The economy of the Nebraska Sandhills region in the late 19th century was dominated by the cattle ranching industry.

Large ranches dotted the landscape, utilizing largely-unclaimed lands in the public domain.

[9] Ranchers would file claims on lands with water access, and use the surrounding public pastures for grazing.

Large stockmen sometimes used fraudulent homestead filings from employees and other individuals in order to gain title to surrounding land.

[11] Due to the immense land holdings required for large cattle operations, the population of the Sandhills region decreased by 10% between 1890 and 1900, and millions of acres remained in the public domain.

[12] To address this issue, William Neville, a populist congressman from North Platte, Nebraska, introduced legislation in 1902 that would amend the Homestead Law to allow an individual to take a homestead of 1,280 acres in the arid and nonirrigable lands west of the 100th meridian.

In his 1902 address to congress, President Theodore Roosevelt made it a priority to settle the "public land problem."

The committee felt that 640 acres would be a good initial experiment size for dry-land farming, and the act could be amended in the future if more land were needed.

[14] It was a bill meant for "the disposition of sandy and arid lands in western Nebraska," which were too difficult to irrigate.

[19] The North Platte Telegraph reported in 1906 that merchants had been having their most profitable months ever due to the influx of new residents.

[20] In her book Old Jules, a memoir about living in the Sandhills region at the turn of the century, Mari Sandoz describes the scene as land was initially opened for settlement: Two weeks before opening, covered wagons, horsebackers, men afoot, toiled into Alliance, got information at the land office, and vanished eastward over the level prairie.

Others kept on, through this protective border, into the broad valley region, with high hills reaching towards the whitish sky.

[21]Population rapidly increased in the 37 counties where the law was applicable:[17] Nearly all of the public lands in the region were claimed by 1912.

But, many of these statements were made by established cattle ranchers and industry representatives who were originally opposed to the Kinkaid Act.

[22] In congressional testimony from 1914, Moses Kinkaid reported that the sentiment of settlers in the region was that most of the claims remained in the hands of individual families.

[23] He reported that the region's communities held many small festivals each year, where Kinkaid homesteaders would meet and display their agricultural products.

[24] He described the average Kinkaid homesteader as a small family farmer: They get cows, so far as they are able, and they go into dairying – those that are able to buy cattle enough to go into the stock business do so.

They raise cane a good deal for feeding, and in some places alfalfa.He estimated that the average Kinkaid homesteader had 15 to 40 head of cattle on 640 acres.

[25] Kinkaid's observations were supported by a 1915 report compiled by the Agricultural Experiment Station at the University of Nebraska.

It found the following results:[27] The report showed that a majority of the land was in the hands of small holders, and approximately half the acreage was still owned by the original claimants.

Because of the difficulties in dry-land farming on such small plots, many Kinkaid homesteaders eventually failed in their attempts to raise crops, and usually sold out to large ranchers.

[29] The Kinkaid Act did convert land to private ownership from the public domain, but its goal of populating the region with small family farms had mixed results.