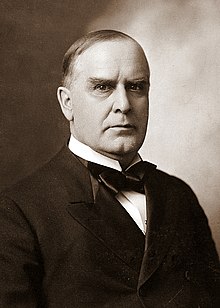

William McKinley

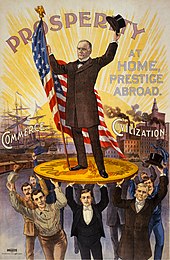

He secured the Republican nomination for president in 1896 amid a deep economic depression and defeated his Democratic rival William Jennings Bryan after a front porch campaign in which he advocated "sound money" (the gold standard unless altered by international agreement) and promised that high tariffs would restore prosperity.

Crook's corps was attached to Major General David Hunter's Army of the Shenandoah and soon back in contact with Confederate forces, capturing Lexington, Virginia, on June 11.

[32] They fended off a Confederate assault at Berryville, where McKinley had a horse shot out from under him, and advanced to Opequon Creek, where they broke the enemy lines and pursued them farther south.

[35] Crook's capture added to the confusion as the army was reorganized for the spring campaign, and McKinley served on the staffs of four different generals over the next fifteen days—Crook, John D. Stevenson, Samuel S. Carroll, and Winfield S.

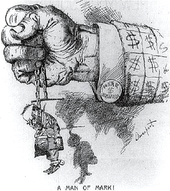

[47] Lynch, McKinley's opponent in the 1871 election, and his partner, William R. Day, were the opposing counsel, and the mine owners included Mark Hanna, a Cleveland businessman.

The primary intention of such imposts was not to raise revenue, but to allow American manufacturing to develop by giving it a price advantage in the domestic market over foreign competitors.

McKinley biographer Margaret Leech noted that Canton had become prosperous as a center for the manufacture of farm equipment because of protection, and that this may have helped form his political views.

[67] McKinley tirelessly stumped his new district, reaching out to its 40,000 voters to explain that his tariff: was framed for the people ... as a defense to their industries, as a protection to the labor of their hands, as a safeguard to the happy homes of American workingmen, and as a security to their education, their wages, and their investments ...

[75] He procured legislation that set up an arbitration board to settle work disputes and obtained passage of a law that fined employers who fired workers for belonging to a union.

Fearing that the Ohio governor would emerge as a candidate, Harrison's managers arranged for McKinley to be permanent chairman of the convention in Minneapolis, requiring him to play a public, neutral role.

Both William and Ida McKinley placed their property in the hands of the fund's trustees (who included Hanna and Kohlsaat), and the supporters raised and contributed a substantial sum of money.

According to historian Stanley Jones in his study of the 1896 election: Another feature common to the Reed and Allison campaigns was their failure to make headway against the tide which was running toward McKinley.

[87] Many of their early efforts were focused on the South; Hanna obtained a vacation home in southern Georgia where McKinley visited and met with Republican politicians from the region.

[90] Wyoming Senator Francis Warren wrote, "The politicians are making a hard fight against him, but if the masses could speak, McKinley is the choice of at least 75% of the entire [body of] Republican voters in the Union".

When Ohio was reached in the roll call of states, its votes gave McKinley the nomination, which he celebrated by hugging his wife and mother as his friends fled the house, anticipating the first of many crowds that gathered at the Republican candidate's home.

In the final days before the convention, McKinley decided, after hearing from politicians and businessmen, that the platform should endorse the gold standard, though it should allow for bimetallism through coordination with other nations.

[100][102][103] Most Democratic newspapers refused to support Bryan, the major exception being the New York Journal, controlled by William Randolph Hearst, whose fortune was based on silver mines.

Dawes eventually became Comptroller of the Currency; he recorded in his published diary that he had strongly urged McKinley to appoint as secretary the successful candidate, Lyman J. Gage, president of the First National Bank of Chicago and a Gold Democrat.

[120] Although McKinley was initially inclined to allow Long to choose his own assistant, there was considerable pressure on the President-elect to appoint Theodore Roosevelt, head of the New York City Police Commission and a published naval historian.

[129][130] In January 1898, Spain promised some concessions to the rebels, but when American consul Fitzhugh Lee reported riots in Havana, McKinley agreed to send the battleship USS Maine.

[137] The expansion of the telegraph and the development of the telephone gave McKinley greater control over the day-to-day management of the war than previous presidents had enjoyed, and he used the new technologies to direct the army's and navy's movements as far as he was able.

[142] The next month, McKinley increased the number of troops sent to the Philippines and granted the force's commander, Major General Wesley Merritt, the power to set up legal systems and raise taxes—necessities for a long occupation.

[154] McKinley proposed to open negotiations with Spain on the basis of Cuban liberation and Puerto Rican annexation, with the final status of the Philippines subject to further discussion.

[160] Foreseeing difficulty in getting two-thirds of the Senate to approve a treaty of annexation, McKinley instead supported the effort of Democratic Representative Francis G. Newlands of Nevada to accomplish the result by joint resolution of both houses of Congress.

[170] Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and his government showed some interest in the idea and told American envoy Edward O. Wolcott that he would be amenable to reopening the mints in India to silver coinage if the Viceroy's Executive Council there agreed.

[200] However, the first lady fell ill in California, causing her husband to limit his public events and cancel a series of speeches he had planned to give urging trade reciprocity.

In that case, he would almost certainly die, since drugs to control infection did not exist ... [Prominent New York City physician] Dr. McBurney was by far the worst offender in showering sanguine assurances on the correspondents.

"[216] Beginning in the 1950s, McKinley received more favorable evaluations; nevertheless, in surveys ranking American presidents, he has generally been placed near the middle, often trailing contemporaries such as Hayes and Cleveland.

[231] Historian Daniel P. Klinghard argued that McKinley's personal control of the 1896 campaign gave him the opportunity to reshape the presidency—rather than simply follow the party platform—by representing himself as the voice of the people.

Historian Michael J. Korzi argued in 2005 that while it is tempting to see McKinley as the key figure in the transition from congressional domination of government to the modern, powerful president, this change was an incremental process through the late 19th and early 20th centuries.