Kisaeng

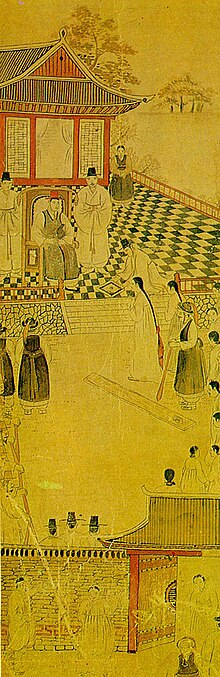

They were carefully trained and frequently accomplished in the fine arts, poetry, and prose, and although they were of low social class, they were respected as educated artists.

[10] Though they were of low social class, the kisaeng held a unique role in ancient Korea's society, and were respected for their career as educated artists and writers.

For this reason, they were sometimes spoken of as "possessing the body of the lower class but the mind of the aristocrat"[11] and as having a "paradoxical identity as a socially despised yet popularly (unofficially) acclaimed artist".

[3] Numerous accounts report individual kisaeng as specializing specifically in arts, music, poetry, and conversation skills.

On occasion, even women from the yangban aristocracy were made kisaeng, usually because they had violated the strict sexual mores of the Joseon period.

[citation needed] In the three-tiered system of later Joseon, more specialized training schools were established for kisaeng of the first tier.

[33] They were laid out to create a welcoming effect; in many cases, a location was chosen with a fine view,[34] and the area around the house would be landscaped with ornamental pools and plantings.

It was through information supplied by kisaeng that the rebel army of Hong Gyeong-nae was able to easily take the fortress of Jongju in the early 19th century.

[38] Many of these worked for the court, and helped to fill the vast number of trained entertainers needed for grand festivals.

[14] The kisaeng of Pyeongyang were also known for their ability to recite the gwan san yung ma, a song by the 18th-century composer Shin Gwangsu.

For instance, in the time of Sejong the Great in the 15th century, there were some sixty kisaeng attached to the army base at Yongbyon.

[43] Those of the Honam region in the southwest were trained in pansori,[40] while those of the seonbi city Andong could recite the Great Learning (Daxue; Daehak) by heart.

For example, the Royal Protocols, or Ǔigwe (의궤; 儀軌), records names of those who worked to prepare for important court rituals, and some kisaeng are listed as needleworkers.

[46] Yet references to kisaeng are quite widespread in the yadam or "anecdotal histories" of later Joseon and Silhak thinkers such as Yi Ik and Jeong Yakyong, known as Dasan, who gave some thought to their role and station in society.

[citation needed] Many others trace their origins to the early years of Goryeo, when many people were displaced following the end of the Later Three Kingdoms period in 936.

During the Joseon dynasty, the kisaeng system continued to flourish and develop, despite the government's deeply ambivalent attitude toward it.

[citation needed] Joseon was founded on Korean Confucianism, and these scholars of the time took a very dim view of professional women and of the kisaeng class in particular.

There were many calls for the abolition of the kisaeng, or for their exclusion from court, but these were not successful—perhaps because of the influence of the women themselves, or perhaps because of fear that officials would take to stealing the wives of other men.

[31] One such proposal was made during the reign of Sejong the Great, but when an advisor of the court suggested that the abolition of the class would lead to government officials committing grave crimes, the king chose to preserve the kisaeng.

Yeonsan-gun treated women as primarily objects of pleasure, and made even the medicinal kisaeng (yakbang gisaeng) into entertainers.

[55] Yeonsan-gun brought 1,000 women and girls from the provinces to serve as palace kisaeng; many of them were paid from the public treasury.

Their role did not, by law, include sexual service to the officeholder; in fact, government officials could be punished severely for consorting with a kisaeng.

[citation needed] The kisaeng were considered to be the lowest of the caste system in the Neo-Confucian way of living that had developed in Korea.

[61] The economic depression that Korea faced at the time of the Japanese occupation led to an impoverished female population being exposed to the labor market.

As the overtaking of Korea by Japan continued, the kisaeng profession responded to social and economic shifts in fashion, schools, and brothel management.

[63][64][65] Most of the kisaeng of this time performed in restaurants or entertainment houses to earn a living, and they were often seen as a tourist attraction for the Japanese in Korea, especially Seoul.

This transition allowed the Japanese police to have control over female bodies through the prostitution licensing system that Japan employed.

However, after the start of the Japanese occupation, the kisaeng had to actively navigate a restructured sex market in colonial Korea.

Chang Han also discussed how the kisaeng of the time were able to interweave femininity with the arts, to create a more cultured approach that allowed them to compete with the licensed prostitutes.

[citation needed] In North Korea, all kisaeng descendants were labelled as members of the 'hostile class' and are considered to have 'bad songbun', i.e. "tainted blood".