Kishinev pogrom

[8] When a Ukrainian boy, Mikhail Rybachenko, was found murdered in the town of Dubăsari, about 40 km (25 mi) north of Kishinev, and a girl who committed suicide by poisoning herself was declared dead in a Jewish hospital, the Bessarabetz paper insinuated that both children had been murdered by the Jewish community for the purpose of using their blood in the preparation of matzo for Passover.

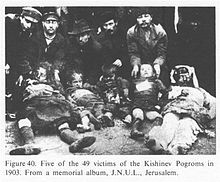

In two days of rioting, 47 (some put the figure at 49) Jews were killed, 92 were severely wounded and 500 were slightly injured, 700 houses were destroyed, and 600 stores were pillaged.

[7][10] The Times published a forged dispatch by Vyacheslav von Plehve, the Minister of Interior, to the governor of Bessarabia, which supposedly gave orders not to stop the rioters.

[7][12] On 28 April, The New York Times reprinted a Yiddish Daily News report that was smuggled out of Russia:[4] The mob was led by priests, and the general cry, "Kill the Jews", was taken-up all over the city.

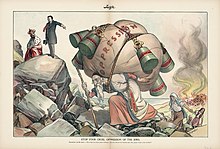

[13] The Kishinev pogrom of 1903 captured the attention of the international public and was mentioned in the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine as an example of the type of human rights abuse which would justify United States involvement in Latin America.

[17] American media mogul William Randolph Hearst "adopt[ed] Kishinev as little less than a crusade", according to Stanford historian Steven Zipperstein.

After interviewing survivors of the Kishinev pogrom, the Hebrew poet Hayim Nahman Bialik (1873–1934) wrote "In the City of Slaughter," about the perceived passivity of the Jews in the face of the mobs.

[22][23] In the 1908 play by Israel Zangwill titled The Melting Pot, the Jewish hero emigrates to America in the wake of the Kishinev pogrom, eventually confronting the Russian officer who led the rioters.

[24] More recently, Joann Sfar's series of graphic novels titled Klezmer depicts life in Odessa, Ukraine, at this time; in the final volume (number 5), Kishinev-des-fous, the first pogrom affects the characters.

[27] In Brazil, the Jewish writer Moacyr Scliar wrote the fiction and social satire book "O Exército De Um Homem Só" (1986), about Mayer Guinzburg, a Brazilian-Jew and Communist activist whose family are refugees from the Kishinev pogrom.

[29] He covered the events and later published a book detailing his findings, which included a list of the victims' names, ages, and, in some instances, their occupations.

[31] The organization JewishGen cross-referenced a wide range of sources and compiled a list of 47 names, though they caution that errors may still exist, suggesting that further research is required to complete the record.