Knanaya

[11] A translation of the epithet in reference to the community is found as “Parcialidad de Thome Cananeo” or “Thomas Canaanite Party” in Archbishop Franciso Ros' text MS. ADD.

A prominent example of this is seen during the "Chandam Charthal" or grooms beautification ceremony, in which the barber petitions the assembly three times with the following request: "I ask the gentlemen here who have superiority over 17 castes, may I shave the bridegroom?".

Connected with the IV century colonization is the origin of those called the Southists"[26] - Dr. Placid J Podipara (1971)Directional divisions within communities are common in Kerala, including among Hindu groups.

[44] Dr. Jacob Kollaparambil notes specifically that the Jewish-Christians of southern Mesopotamia (modern day Iraq) were the most vehement in maintaining their Jewish ethnicity, even after conversion to Syriac Christianity.

Winkworth produced the following citation presented at the International Congress of Orientalist (Oxford): "My Lord Christ, have mercy upon Afras son of Chahar-bukht, the Syrian who cut this"[51]The first written evidence of a Knanaya individual dates to the year 1301, with the writings of Zacharias the deacon of St. Kuriakose Church, Cranganore.

The historical Knanaya folk song "Alappan Adiyil" written on palm-leaf manuscript records the reconstruction of Kaduthuruthy Church and includes the colophon date 1456.

[8] In 1525, Mar Jacob, a Chaldean bishop in India, recorded a battle the year before between the Kingdom of Cochin and the Zamorin of Calicut that destroyed Cranganore and many Knanaya homes and churches.

[60][61][62] After the death of their king, soldiers of the Kingdom of Vadakkumkur formed themselves into chaver (suicide) squads and sought revenge against the Syrian Christians in the region who they viewed as co-religionist of the Portuguese.

[65] De Gouvea states that the loss of the plates had angered the Knanaya who had no other written record of their history and rights to defend themselves from local kings who by this point were infringing on their position.

9853, 1604) Ros further notes that discord arose between the Knanaya and Northist St. Thomas Christians to the point where it became necessary to build separate churches in the regions of Carturte (Kaduthuruthy) and Cotete (Kottayam).

9853, 1604) In 1611, chronicler and historian of Portuguese India Diogo de Couto mentions the tradition that a contingent of families had accompanied Thomas of Cana and notes that these Christians are "without doubt Armenians by caste; and their sons too the same, because they had brought their wives".

[69][35] Do Couto's account: "From the people who had come with him proceed the Christians of Diamper, Kottayam and Kaduthuruthy, who without doubt are Armenians by caste, and their sons too the same, because they had brought their wives; and afterwards those who descended from them married in the land, and in the course of time they all became Malabarians.

Decada XII, 1611) Other Portuguese authors who wrote of the Southist-Northist divide, generally referencing versions of the Thomas of Cana’s arrival, include Franciscan friar Paulo da Trinidade (1630–1636),[70] and Bishop Giuseppe Maria Sebastiani (1657).

[35][71] Sebastiani notes that in demographics the Knanaya numbered no more than 5000 persons in the 17th century and out of the 85 parishes of the Malabar Christians are only found in Udiamperoor, Kottayam, Thodupuzha (Chunkom), and Kaduthuruthy.

[71] After the death of Mar Abraham in 1599 (the last East Syriac bishop of Kerala), the Portuguese began to aggressively impose their dominion over the church and community of the St. Thomas Christians.

[76] In mass rebellion against the Portuguese clergy and in particular Archbishop Francisco Garcia Mendes, the St. Thomas Christians met on 3 January 1653 at Our Lady of Mattenchery Church to convoke the Coonan Cross Oath.

[76] After the oath, scholar Stephen Neill notes that the Knanaya priest Anjilimoottil Itty Thommen Kathanar of Kallissery played a major role in the eventual schism of the St. Thomas Christians from the Roman Catholic Church.

Being a skilled Syriac writer, it is believed that Itty Thommen forged two letters supposedly from Mor Ahatallah one of which stated that in the absence of a bishop, twelve priests could lay hands on Archdeacon Thomas and consecrate him as their new patriarch, an old oriental Christian tradition.

Archbishop and successor of Fransico Garcia, Giuseppe Maria Sebastiani noted that the Knanaya greatly supported Parambil Chandy even though he was a Northist St. Thomas Christian.

To welcome this offer in his presence I warmly recommended him and his Christians and Churches to the Monsignor of Megara (Mar Alexander Parambil), who said that he was acknowledging their zeal and fervor, and that he would always protect, help and conserve them with his very life, much more than the others called Vadakumbhagam" - Bishop Giuseppe Maria Sebastiani, 1663 (Published in Seconda Speditione All' Indie Orientale in 1672)Parambil Chandy would be ordained as the Catholic bishop of the St. Thomas Christians in 1663 at Kaduthuruthy Knanaya Church.

[84] When the migrants arrived in the year 345, they were met by the Native St. Thomas Christians and later approached the King of Malabar from whom they received land and privileges in the form of copper plates.

[86] The tension between the Native Clergy and Roman Church met a breaking point when the Latin hierarchy had imprisoned and starved to death Northist Cathanar (Syriac priest) Chacko of Edappalli in 1774, who was wrongfully accused of stealing a monstrance.

[87] After this, the Malabar General Church Assembly had joined in the venture of sending a delegation to Rome in order to meet the pope and have their grievances addressed as well as petition for the ordination of a native Syrian Catholic hierarch.

The similarities become significant when the Knanites claim a Jewish origin"[97]A cultural difference between the Knanaya and other St. Thomas Christians was noted by Dr. Joseph Cariattil, the ecclesial head of the Syrian Catholics of Kerala.

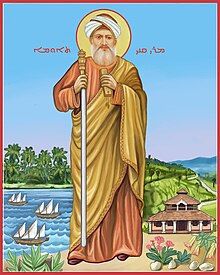

The contents of the story revolves around a mission bestowed to Tiruvaranka by Thomas of Cana in which he is to travel to Ezhathunadu (Sri Lanka) and implore four castes, namely carpenters, blacksmiths, goldsmiths, and molders, to return to Cranganore which they had left due to an infringement on their social traditions.

The four castes are initially hesitant to return to Cranganore but are persuaded by Tiruvaranka when he shows them the golden staff of Thomas of Cana which he was granted to take on his journey as a sign of goodwill.

At the end of the marriage ceremony, the priests and congregation sing the "Bar Mariam" ("Son of Mary"), a "paraliturgical" Syriac chant referencing events from Jesus' life.

[117] Special seats called manarcolam (marriage venue) are prepared for the couple by spreading sheets of wool and white linen, representing the hardships and blessings of married life.

Catholic and Orthodox Knanaya dining together would eat from the left and right side of the leaf to show that despite their different religious affiliations, they were still part of a united ethnic community.

The mundu is a long white cloth worn from the waist down, and includes 15 to 21 pleats covering the back thigh in a fan shape representing a palm leaf.