Knight's tour

Creating a program to find a knight's tour is a common problem given to computer science students.

[3] Variations of the knight's tour problem involve chessboards of different sizes than the usual 8 × 8, as well as irregular (non-rectangular) boards.

[4] The earliest known reference to the knight's tour problem dates back to the 9th century AD.

In Rudrata's Kavyalankara[5] (5.15), a Sanskrit work on Poetics, the pattern of a knight's tour on a half-board has been presented as an elaborate poetic figure (citra-alaṅkāra) called the turagapadabandha or 'arrangement in the steps of a horse'.

The same verse in four lines of eight syllables each can be read from left to right or by following the path of the knight on tour.

Since the Indic writing systems used for Sanskrit are syllabic, each syllable can be thought of as representing a square on a chessboard.

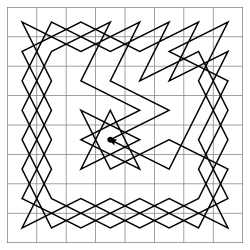

The Sri Vaishnava poet and philosopher Vedanta Desika, during the 14th century, in his 1,008-verse magnum opus praising the deity Ranganatha's divine sandals of Srirangam, Paduka Sahasram (in chapter 30: Chitra Paddhati) has composed two consecutive Sanskrit verses containing 32 letters each (in Anushtubh meter) where the second verse can be derived from the first verse by performing a Knight's tour on a 4 × 8 board, starting from the top-left corner.

[6] The transliterated 19th verse is as follows: (1) (30) (9) (20) (3) (24) (11) (26) (16) (19) (2) (29) (10) (27) (4) (23) (31) (8) (17) (14) (21) (6) (25) (12) (18) (15) (32) (7) (28) (13) (22) (5) The 20th verse that can be obtained by performing Knight's tour on the above verse is as follows: sThi thA sa ma ya rA ja thpA ga tha rA mA dha kE ga vi | dhu ran ha sAm sa nna thA dhA sA dhyA thA pa ka rA sa rA || It is believed that Desika composed all 1,008 verses (including the special Chaturanga Turanga Padabandham mentioned above) in a single night as a challenge.

The most notable example is the 10 × 10 knight's tour which sets the order of the chapters in Georges Perec's novel Life a User's Manual.

Schwenk[10] proved that for any m × n board with m ≤ n, a closed knight's tour is always possible unless one or more of these three conditions are met: Cull et al. and Conrad et al. proved that on any rectangular board whose smaller dimension is at least 5, there is a (possibly open) knight's tour.

A brute-force search for a knight's tour is impractical on all but the smallest boards.

It is possible to have two or more choices for which the number of onward moves is equal; there are various methods for breaking such ties, including one devised by Pohl[20] and another by Squirrel and Cull.

[22] Although the Hamiltonian path problem is NP-hard in general, on many graphs that occur in practice this heuristic is able to successfully locate a solution in linear time.

[23] The heuristic was first described in "Des Rösselsprungs einfachste und allgemeinste Lösung" by H. C. von Warnsdorf in 1823.

[23] A computer program that finds a knight's tour for any starting position using Warnsdorf's rule was written by Gordon Horsington and published in 1984 in the book Century/Acorn User Book of Computer Puzzles.

[24] The knight's tour problem also lends itself to being solved by a neural network implementation.

Although divergent cases are possible, the network should eventually converge, which occurs when no neuron changes its state from time