Mechanical Turk

Kempelen was inspired to build the Turk following his attendance at the court of Maria Theresa of Austria at Schönbrunn Palace, where François Pelletier was performing an illusion act.

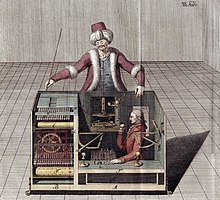

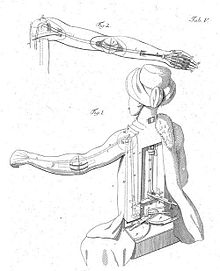

The machine consisted of a life-sized model of a human head and torso, with a black beard and grey eyes,[6] and dressed in Ottoman robes and a turban—"the traditional costume", according to journalist and author Tom Standage, "of an oriental sorcerer".

"[5] The interior also contained a pegboard chess board connected to a pantograph-style series of levers that controlled the model's left arm.

Along with other challengers that day, he was quickly defeated, with observers of the match stating that the machine played aggressively, and typically beat its opponents within thirty minutes.

Von Windisch wrote at one point that Kempelen "refused the entreaties of his friends, and a crowd of curious persons from all countries, the satisfaction of seeing this far-famed machine".

[26] Kempelen was quoted as referring to the invention as a "mere bagatelle", as he was not pleased with its popularity and would rather continue work on steam engines and machines that replicated human speech.

[27] In 1781, Kempelen was ordered by Emperor Joseph II to reconstruct the Turk and deliver it to Vienna for a state visit from Grand Duke Paul of Russia and his wife.

The appearance was so successful that Grand Duke Paul suggested a tour of Europe for the Turk, a request to which Kempelen reluctantly agreed.

Upon arrival in Paris in May 1783, it was displayed to the public and played a variety of opponents, including a lawyer named Mr. Bernard who was a second rank in chess ability.

[30] Moving to the Café de la Régence, the machine played many of the most skilled players, often losing (e.g. against Bernard and Verdoni),[31] until securing a match with Philidor at the Académie des Sciences.

Franklin reportedly enjoyed the game with the Turk and was interested in the machine for the rest of his life, keeping a copy of Philip Thicknesse's book The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player, Exposed and Detected in his personal library.

According to an eyewitness report, Mälzel took responsibility for the construction of the machine while preparing the game, and the Turk (Johann Baptist Allgaier) saluted Napoleon before the start of the match.

Napoleon was reportedly amused, and then played a real game with the machine, completing nineteen moves before tipping over his king in surrender.

[c] Following the repurchase, Mälzel brought the Turk back to Paris, where he made acquaintances of many of the leading chess players at Café de la Régence.

In 1826, he opened an exhibition in New York City that slowly grew in popularity, giving rise to many newspaper stories and anonymous threats of exposure of the secret.

Following Philadelphia, the Turk moved to Baltimore, where it played for a number of months, including losing a match against Charles Carroll, a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

As the Turk was lost to fire at the time of this publication, Silas Mitchell felt that there were "no longer any reasons for concealing from the amateurs of chess, the solution to this ancient enigma".

[63] The most important biographical history about the Chess-player and Mälzel was presented in The Book of the First American Chess Congress, published by Daniel Willard Fiske in 1857.

[68] Later in 1859, an uncredited article appeared in Littell's Living Age that purported to be the story of the Turk from French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin.

This was rife with errors ranging from dates of events to a story of a Polish officer whose legs were amputated, but ended up being rescued by Kempelen and smuggled back to Russia inside the machine.

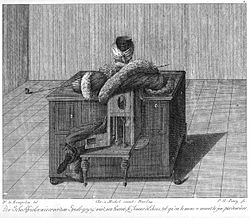

Another article written in 1960 for American Heritage by Ernest Wittenberg provided new diagrams describing how the operator sat inside the cabinet.

[76] El Ajedrecista was built in 1912 by Leonardo Torres Quevedo as a chess-playing automaton and made its public debut during the Paris World Fair of 1914.

[79] Raymond Bernard's silent feature film The Chess Player (1927) weaves elements from the real story of the Turk into an adventure tale set in the aftermath of the first of the Partitions of Poland in 1772.

[81] Ambrose Bierce's short story "Moxon's Master", published in 1909, is a morbid tale about a chess-playing automaton that resembles the Turk.

[83] Gene Wolfe's 1977 science fiction short story "The Marvellous Brass Chessplaying Automaton" also features a device very similar to the Turk.

[85] Jingetsu Isomi's 2013 manga series Chrono Monochrome is about a 21st-century Japanese child chess prodigy who travels back in time and becomes the Turk's original operator.

In 2023, the story "Alone Together" from the Tales from the Pizzaplex book series, itself a part of the Five Nights at Freddy's franchise, features a Mechanical Turk as a school project.

Walter Benjamin alludes to the Mechanical Turk in the first thesis of his Theses on the Philosophy of History (Über den Begriff der Geschichte), written in 1940.

[86] The Mechanical Turk appears as part of a ritual for the Stranger, an entity that manifests via the uncanny valley, in episode 116, "The Show Must Go On", of the British horror podcast The Magnus Archives.

In the sci-fi TV series Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles an artificial intelligence chess-playing computer called "The Turk" is an important part of the plot.