Knoxville riot of 1919

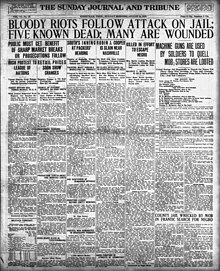

The riot began when a lynch mob stormed the county jail in search of Maurice Mays, a biracial man who had been accused of murdering a white woman.

Unable to find Mays, the rioters looted the jail and fought a pitched gun battle with the residents of a predominantly black neighborhood.

[6] After the riot, many black residents left Knoxville, and racial violence continued to flare up sporadically in subsequent years.

[1] In the decades following the Civil War, Knoxville was considered by both black and white residents to be one of the few racially tolerant cities in the South.

[1] In 1918, Charles W. Cansler (1871–1953), one of the city's leading African-American citizens, wrote to the governor of Tennessee, "In no place in the world can there be found better relations existing between the races than here in our own county of Knox.

[1] Furthermore, in the summer of 1919, a prowler known as "Pants," described by victims as a light-skinned Negro, had been burglarizing homes and attacking white women, though he had attracted little attention from Knoxville police.

[1] Patrolman White suggested they question Maurice Mays, a prominent mulatto who operated the Stroller's Cafe on East Jackson.

[1] By noon, news of the murder had spread, and a crowd of curious onlookers had gathered at the county jail, thinking Mays was being held there.

[7] Two platoons of the Tennessee National Guard's 4th Infantry, led by Adjutant General Edward Sweeney, arrived, but they were unable to halt the chaos.

[1] After looting the jail and Sheriff Cate's house, the mob returned to Market Square, where they dispatched five truckloads of rioters to Chattanooga to find Mays.

Meanwhile, many of the city's black residents, aware of the race riots that had occurred across the country that summer, had armed themselves, and had barricaded the intersection of Vine and Central to defend their businesses.

One guardsman, 24-year-old Lieutenant James William Payne, was shot and wounded by a sniper, and as he staggered into the street, he was cut to pieces by friendly fire from the machine guns.

Among those killed was a black shopkeeper and Spanish–American War veteran named Joe Etter, who was shot when he attempted single-handedly to capture one of the machine guns.

[1] Some of Knoxville's newspapers placed the death toll at just two white people (Etter and Payne), though eyewitness accounts say it was much higher.

[1] A list of people hospitalized with wounds was published in the Chattanooga Daily Times on September 1:[11] A Covington, Tennessee newspaper stated that the dead were Payne, a private by the last name of Henderson, Jim Henson and two "unidentified negroes" and among the wounded were:[12] In the weeks following the riot, many of the city's African-American leaders argued that the rioters did not represent the typical attitude of Knoxville's white citizens,[1] though hundreds of black residents nevertheless left the city for good.

The Knoxville Journal denied a race riot had occurred, insisting the entire incident was nothing more than the city's "rabble" running amok.

[1] According to Tennessee attorney general R.A. Mynatt in 1920, one person involved in the riots was sent to the penitentiary for one to five years, another was convicted but appealed to the Supreme Court, a third "leader of the mob is still sought.

[8] Shortly after 6:00 am on the morning of March 15, 1922, Maurice Mays was led from his cell and strapped to the electric chair at Tennessee State Prison in Nashville.