Wilmington massacre

[13] With the end of the war in 1865, freedmen who lived in many states left plantations and rural areas and moved to towns and cities to seek work, but also to gain safety by creating black communities without white supervision.

[14] However, conservative white Democrats, who had previously dominated politics in the state, greatly resented this "radical" change, which they deemed as being brought about by black residents, Unionist "carpetbaggers", and race traitors referred to as "scalawags".

[16] However, in that region, poor white cotton farmers were often more fed up with the tactics of big banks and railroad companies, who charged high freight rates and used laissez-faire economics that worked against the already impoverished South.

[18] By 1898, Wilmington's key political power was in the hands of "The Big Four", who were representative of the Fusion ticket: the mayor Dr. Silas P. Wright; the acting sheriff of New Hanover County, George Zadoc French; the postmaster, W. H. Chadbourn; and businessman, Flaviel W. Fosters, who wielded substantial support and influence with black voters.

Defeated at the polls and in the courtroom, the Democrats, desperate to avoid another loss, became aware of discord between the Fusion alliance of black Republicans and white Populists, although it appeared that the Fusionists would sweep the upcoming elections of 1898, if voters voted on the following issues.

[32] These men, the "Secret Nine" —Hugh MacRae, J. Allan Taylor, Hardy L. Fennell, W. A. Johnson, L. B. Sasser, William Gilchrist, P. B. Manning, E. S. Lathrop, and Walter L. Parsley—banded together and began conspiring to re-take control of the city government.

He later admitted he had remembered what Populist Senator Marion Butler had written the previous year in his newspaper, The Caucasian: There is but one chance and but one hope for the railroads to capture the net [sic] legislature, and that is for the nigger to be made the issue.

With the aid of Daniels, who would distribute racist propaganda that he later acknowledged helped fuel a "reign of terror" (i.e., disparaging cartoons of blacks) before speeches, Waddell, and the other orators, began appealing to white men to join their cause.

[17][74] Four days later, 50 of Wilmington's most prominent white men, such as Robert Glenn, Thomas Jarvis, Cameron Morrison and Charles Aycock, who was now the pre-eminent orator of the campaign, packed the Thalian Hall opera house.

He deemed blacks to be "ignorant" and railed that "the greatest crime that has ever been perpetrated against modern civilization was the investment of the negro with the right of suffrage", and he advocated punishment for race-traitors for enabling it, cementing his call with a blistering closing:[17][18][76] We will never surrender to a ragged raffle of Negroes, even if we have to choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses.Waddell's closing became a rallying cry, for white men and women alike: This I do not believe for a moment that they will submit any longer it is time for the oft quoted shotgun to play a part, and an active one, in the elections ... We applaud to the echo your determination that our old historic river should be choked with the bodies of our enemies, white and black, but what his state shall be redeemed.

They destroyed property, ambushed citizens with weapon fire, and kidnapped people from their homes and whipped them at night, with the goal of terrorizing them to the point where Republican sympathizers would be too afraid to vote, or even register to do so.

Several Populists began trying to fight back in the court of public opinion, like Oliver Dockery, who was attacked by John Bellamy at the white supremacy convention:[41][53] You may abuse me, if you like, but I want to tell you that you will never make a duck ...

Wherein is negro domination responsible for the Democratic judges who have sat on the bench in recent years in a state of beastly intoxication and sentenced innocent men to the penitentiary and allowed rogues and murders to go free?

They told the business community of this outcome: ... [the election] threatens to provoke a war between the black and white races ... [that] will precipitate a conflict which may cost hundreds, and perhaps thousands, of lives, and the partial or entire destruction of the city.

The city might have been preparing for a siege instead of an election ... All shades of political beliefs were represented: but in the presence of what they believed to be an overwhelming crisis, they brushed aside the great principles that divide parties and individuals, and stood together as one man.

When I emphasize the fact, that every block in every ward was thus organized, and that the precautionary meetings were attended by ministers, lawyers, doctors, merchants, railroad officials, cotton exporters, and, indeed, by the reputable, taxpaying, substantial men of the city, the extent and significance of this armed movement can, perhaps, be realized.

It was not the wild and freakish organization of irresponsible men, but the deliberate action of determined citizens ... Military preparations, so extensive as to suggest assault from some foreign foe, must have had unusual inspiration and definite purpose.

From their churches and from their lodges had come reports of incendiary speeches, of impassioned appeals to the blacks to use the bullet that had no respect for color, and the kerosene and torch that would play havoc with the white man's cotton in bale and ware house.

[17] As Waddell led a group to disband and drive out the elected government of the city, a white mob, armed with shotguns, attacked black people throughout Wilmington, but primarily in Brooklyn, the majority-black neighborhood.

Governor Russell authorized Walker Taylor to lead Wilmington Light Infantry troops, just returned from the Spanish–American War, and units of the federal Naval Reserves into Brooklyn to quell the "riot".

All colored men at the cotton press and oil mills were ordered not to leave their labor but stop there, while their wives and children were shrieking and crying in the midst of the flying balls and in sight of the cannons and Gatling gun.

[140][141] Despite vowing to "choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses", and the fact that some members of the white mob posed for a photograph in front of the charred remnants of The Daily Record, in the article Waddell painted himself as a reluctant, non-violent leader – or accidental hero – "called upon" to lead under "intolerable conditions".

Charles S. Morris, told his account of the event before the International Association of Colored Clergymen in January 1899: Nine Negroes massacred outright; a score wounded and hunted like partridges on the mountain; one man, brave enough to fight against such odds would be hailed as a hero anywhere else, was given the privilege of running the gauntlet up a broad street, where he sank ankle deep in the sand, while crowds of men lined the sidewalks and riddled him with a pint of bullets as he ran bleeding past their doors; another Negro shot twenty times in the back as he scrambled empty handed over a fence; thousands of women and children fleeing in terror from their humble homes in the darkness of the night ... crouched in terror from the vengeance of those who, in the name of civilization, and with the benediction of the ministers of the Prince of Peace, inaugurated the reformation of the city of Wilmington the day after the election by driving out one set of white office holders and filling their places with another set of white office holders – the one being Republican and the other Democrat.

All this happened, not in Turkey, nor in Russia, nor in Spain, not in the gardens of Nero, nor in the dungeons of Torquemada, but within three hundred miles of the White House, in the best State in the South, within a year of the twentieth century, while the nation was on its knees thanking God for having enabled it to break the Spanish yoke from the neck of Cuba.

[149] The branding of the event as a "riot", "insurrection", "rebellion", "revolution", or "conflict", largely remained until the late 20th century due to the accounts of black survivors being minimized, ignored and omitted – as with The Daily Record destroyed, there were no media outlets to provide recorded accounts of blacks – and due to the South's adoption of Jubal Early's literary and cultural point of view of The Lost Cause, in which violence perpetuated by whites, across American Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Jim Crow era, evolved into a language of vindication and renewal.

[157] By the early 1990s, different groups in the city told and understood different histories of the events, sparking interest to discuss and commemorate the coup, following efforts to recognize similar atrocities in which white-led mobs destroyed the black communities, such as in Rosewood and Tulsa, respectively.

[158][159] In 1995, informal conversations began among the African-American community, UNC-Wilmington's university faculty, and civil rights activists in order to educate residents about what really happened on that day, and to agree on a monument to memorialize the event.

The Commission produced a lengthy report on the event, authored by state archivist, LeRae Umfleet, finding that the violence was "part of a statewide effort to put white supremacist Democrats in office and stem the political advances of black citizens".

What is "sometimes labeled a race riot or rebellion" was actually the actions of law-abiding white Democrats rescuing the city from Republican and carpetbagger corruption, compounded by ignorant, misled negroes who were in no way capable of voting intelligently.

[citation needed] Several commemorations of the event have taken place: We apologize to the black citizens and their descendants whose rights and interests we disregarded and to all North Carolinians, whose trust we betrayed by our failure to fairly report the news and stand firm against injustice.

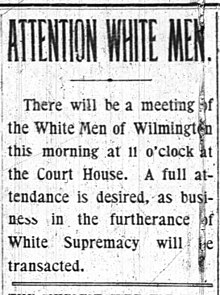

Illustration by Norman Jennett.

September 27, 1898.

November 3, 1898.