Constantinople

In East and South Slavic languages, including in Kievan Rus', Constantinople has been referred to as Tsargrad (Царьград) or Carigrad, 'City of the Caesar (Emperor)', from the Slavonic words tsar ('Caesar' or 'King') and grad ('city').

Constantinople was founded by the Roman emperor Constantine I (272–337) in 324[6] on the site of an already-existing city, Byzantium, which was settled in the early days of Greek colonial expansion, in around 657 BC, by colonists of the city-state of Megara.

Hesychius of Miletus wrote that some "claim that people from Megara, who derived their descent from Nisos, sailed to this place under their leader Byzas, and invent the fable that his name was attached to the city".

Hesychius also gives alternate versions of the city's founding legend, which he attributed to old poets and writers:[32] It is said that the first Argives, after having received this prophecy from Pythia, Blessed are those who will inhabit that holy city, a narrow strip of the Thracian shore at the mouth of the Pontos, where two pups drink of the gray sea, where fish and stag graze on the same pasture, set up their dwellings at the place where the rivers Kydaros and Barbyses have their estuaries, one flowing from the north, the other from the west, and merging with the sea at the altar of the nymph called Semestre" The city maintained independence as a city-state until it was annexed by Darius I in 512 BC into the Persian Empire, who saw the site as the optimal location to construct a pontoon bridge crossing into Europe as Byzantium was situated at the narrowest point in the Bosphorus strait.

[36] It was a move greatly criticized by the contemporary consul and historian Cassius Dio who said that Severus had destroyed "a strong Roman outpost and a base of operations against the barbarians from Pontus and Asia".

The emperor stimulated private building by promising householders gifts of land from the imperial estates in Asiana and Pontica and on 18 May 332 he announced that, as in Rome, free distributions of food would be made to the citizens.

After the shock of the Battle of Adrianople in 378, in which Valens and the flower of the Roman armies were destroyed by the Visigoths within a few days' march, the city looked to its defences, and in 413–414 Theodosius II built the 18-metre (60-foot)-tall triple-wall fortifications, which were not to be breached until the coming of gunpowder.

Uldin, a prince of the Huns, appeared on the Danube about this time and advanced into Thrace, but he was deserted by many of his followers, who joined with the Romans in driving their king back north of the river.

Throughout the late Roman and early Byzantine periods, Christianity was resolving fundamental questions of identity, and the dispute between the orthodox and the monophysites became the cause of serious disorder, expressed through allegiance to the chariot-racing parties of the Blues and the Greens.

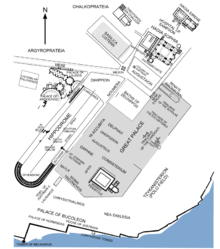

This was the great cathedral of the city, whose dome was said to be held aloft by God alone, and which was directly connected to the palace so that the imperial family could attend services without passing through the streets.

Justinian was also concerned with other aspects of the city's built environment, legislating against the abuse of laws prohibiting building within 100 ft (30 m) of the sea front, in order to protect the view.

[57] In the 730s Leo III carried out extensive repairs of the Theodosian walls, which had been damaged by frequent and violent attacks; this work was financed by a special tax on all the subjects of the Empire.

[58] Theodora, widow of the Emperor Theophilus (died 842), acted as regent during the minority of her son Michael III, who was said to have been introduced to dissolute habits by her brother Bardas.

[59] In 860, an attack was made on the city by a new principality set up a few years earlier at Kiev by Askold and Dir, two Varangian chiefs: Two hundred small vessels passed through the Bosporus and plundered the monasteries and other properties on the suburban Princes' Islands.

Oryphas, the admiral of the Byzantine fleet, alerted the emperor Michael, who promptly put the invaders to flight; but the suddenness and savagery of the onslaught made a deep impression on the citizens.

It is said that, in 1038, they were dispersed in winter quarters in the Thracesian Theme when one of their number attempted to violate a countrywoman, but in the struggle she seized his sword and killed him; instead of taking revenge, however, his comrades applauded her conduct, compensated her with all his possessions, and exposed his body without burial as if he had committed suicide.

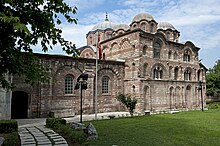

The emperor Leo III issued a decree in 726 against images, and ordered the destruction of a statue of Christ over one of the doors of the Chalke, an act that was fiercely resisted by the citizens.

On his release, however, Romanus found that enemies had placed their own candidate on the throne in his absence; he surrendered to them and suffered death by torture, and the new ruler, Michael VII Ducas, refused to honour the treaty.

The Crusaders occupied Galata, broke the defensive chain protecting the Golden Horn, and entered the harbour, where on 27 July they breached the sea walls: Alexios III fled.

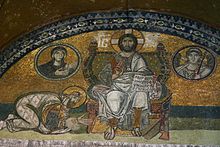

In Hagia Sophia itself, drunken soldiers could be seen tearing down the silken hangings and pulling the great silver iconostasis to pieces, while sacred books and icons were trampled under foot.

Alice-Mary Talbot cites an estimated population for Constantinople of 400,000 inhabitants; after the destruction wrought by the Crusaders on the city, about one third were homeless, and numerous courtiers, nobility, and higher clergy, followed various leading personages into exile.

"[81] Buildings were not the only targets of officials looking to raise funds for the impoverished Latin Empire: the monumental sculptures which adorned the Hippodrome and fora of the city were pulled down and melted for coinage.

In 1261, Constantinople was captured from its last Latin ruler, Baldwin II, by the forces of the Nicaean emperor Michael VIII Palaiologos under the command of Caesar Alexios Strategopoulos.

[86] Military defeats, civil wars, earthquakes and natural disasters were joined by the Black Death, which in 1347 spread to Constantinople, exacerbated the people's sense that they were doomed by God.

[87][88] Castilian traveler and writer Ruy González de Clavijo, who saw Constantinople in 1403, wrote that the area within the city walls included small neighborhoods separated by orchards and fields.

In addition there were volunteers from outside, the "Genoese, Venetians and those who came secretly from Galata to help the defense", who numbered "hardly as many as three thousand", amounting to something under 8,000 men in total to defend a perimeter wall of twelve miles.

[100][101] It was especially important for preserving in its libraries manuscripts of Greek and Latin authors throughout a period when instability and disorder caused their mass-destruction in western Europe and north Africa: On the city's fall, thousands of these were brought by refugees to Italy, and played a key part in stimulating the Renaissance, and the transition to the modern world.

Its city walls were much imitated (for example, see Caernarfon Castle) and its urban infrastructure was moreover a marvel throughout the Middle Ages, keeping alive the art, skill and technical expertise of the Roman Empire.

The 18-meter-tall walls built by Theodosius II were, in essence, impregnable to the barbarians coming from south of the Danube river, who found easier targets to the west rather than the richer provinces to the east in Asia.

[110] Constantinople's fame was such that it was described even in contemporary Chinese histories, the Old and New Book of Tang, which mentioned its massive walls and gates as well as a purported clepsydra mounted with a golden statue of a man.