John II Komnenos

John II Komnenos or Comnenus (Greek: Ἱωάννης ὁ Κομνηνός, romanized: Iōannēs ho Komnēnos; 13 September 1087 – 8 April 1143) was Byzantine emperor from 1118 to 1143.

John was a pious and dedicated monarch who was determined to undo the damage his empire had suffered following the Battle of Manzikert, half a century earlier.

[1] This view became entrenched due to its espousal by George Ostrogorsky in his influential book History of the Byzantine State, where John is described as a ruler who, "... combined clever prudence with purposeful energy ... and [was] high principled beyond his day.

"[2] In the course of the quarter-century of his reign, John made alliances with the Holy Roman Empire in the west, decisively defeated the Pechenegs, Hungarians and Serbs in the Balkans, and personally led numerous campaigns against the Turks in Asia Minor.

John's campaigns fundamentally changed the balance of power in the east, forcing the Turks onto the defensive; they also led to the recapture of many towns, fortresses and cities across the Anatolian peninsula.

[15][16] In a recent biography of Anna, however, this account of events has been disputed, in particular the involvement of John's sister in any palace coup attempt during the days around Alexios' death, has been questioned.

It has been suggested that references to Axouch's possession of the imperial seal early in the reign of John's successor Manuel I meant that he was, in addition to his military duties, the head of the civil administration of the Empire.

John appointed a number of his father's former officials to senior administrative posts, men such as Eustathios Kamytzes, Michaelitzes Styppeiotes and George Dekanos.

[21] A number of 'new men' were raised to prominence by John II, these included Gregory Taronites who was appointed protovestiarios, Manuel Anemas and Theodore Vatatzes, the latter two also became his sons-in-law.

[27] The increase in military security and economic stability within Byzantine western Anatolia created by John II's campaigns allowed him to begin the establishment of a formal provincial system in these regions.

[34] In the East John attempted, like his father, to exploit the differences between the Seljuq Sultan of Iconium and the Danishmendid dynasty controlling the northeastern, inland, parts of Anatolia.

The Byzantine desire to be seen as holding a level of suzerainty over all of the Crusader states was taken seriously, as evidenced by the alarm shown in the Kingdom of Jerusalem when John informed King Fulk of his plan for an armed pilgrimage to the Holy City (1142).

Only when religion impinged directly on imperial policy, as in relations with the papacy and the possible union of the Greek and Latin churches, did John take an active part.

[37] John, alongside his wife who shared in his religious and charitable works, is known to have undertaken church building on a considerable scale, including construction of the Monastery of Christ Pantokrator (Zeyrek Mosque) in Constantinople.

It had twin domes, and is described in the typikon of the monastery as being in the form of a heroon; this emulates the older mausolea of Constantine and Justinian in the Church of the Holy Apostles.

[43] Though he fought a number of notable pitched battles, the military strategy of John II relied on taking and holding fortified settlements in order to construct defensible frontiers.

John surrounded the Pechenegs as they burst into Thrace, tricked them into believing that he would grant them a favourable treaty, and then launched a devastating surprise attack upon their fortified camp.

The ensuing Battle of Beroia was hard-fought, John was wounded in the leg by an arrow, but by the end of the day the Byzantine army had won a crushing victory.

The decisive moment of the battle was when John led the Varangian Guard, largely composed of Englishmen, to assault defensive Pecheneg wagon laager, employing their famous axes to hack their way in.

But this produced further retaliation, and a Venetian fleet of 72 ships plundered Rhodes, Chios, Samos, Lesbos, Andros and captured Kefalonia in the Ionian Sea.

[50][51][c] John launched a punitive raid against the Serbs, who had dangerously aligned themselves with Hungary, many of whom were rounded up and transported to Nicomedia in Asia Minor to serve as military colonists.

In order to restore the region to Byzantine control, he led a series of well planned and executed campaigns against the Turks, one of which resulted in the reconquest of the ancestral home of the Komnenoi at Kastamonu (Kastra Komnenon); he then left a garrison of 2,000 men at Gangra.

Yet resistance, particularly from the Danishmends of the northeast, was strong, and the difficult nature of holding the new conquests is illustrated by the fact that Kastamonu was recaptured by the Turks even as John was in Constantinople celebrating its return to Byzantine rule.

[35][57][58] In the spring of 1139, the emperor campaigned with success against Turks, probably nomadic Turkomans, who were raiding the regions along the Sangarios River, striking their means of subsistence by driving off their herds.

[66] Although John fought hard for the Christian cause in the campaign in Syria, his allies Prince Raymond of Antioch and Count Joscelin II of Edessa remained in their camp playing dice and feasting instead of helping to press the siege of the city of Shaizar.

Joscelin and Raymond conspired to delay the promised handover of Antioch's citadel to the emperor, stirring up popular unrest in the city directed at John and the local Greek community.

John descended rapidly on northern Syria, forcing Joscelin II of Edessa to render hostages, including his daughter, as a guarantee of his good behaviour.

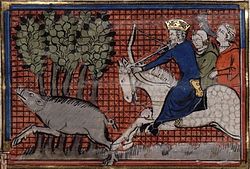

[62] Having prepared his army for a renewed attack on Antioch, John amused himself by hunting wild boar on Mount Taurus in Cilicia, where he accidentally cut himself on the hand with a poisoned arrow.

[73] It has been suggested that John was assassinated by a conspiracy within the units of his army of Latin origins who were unhappy at fighting their co-religionists of Antioch, and who wanted to place his pro-western son Manuel on the throne.

[79] Also, though it was relatively easy to extract submission and admissions of vassalage from the Anatolian Turks, Serbs and Crusader States of the Levant, converting these relationships into concrete gains for the security of the Empire had proven elusive.