Kosher animals

These dietary laws ultimately derive from various passages in the Torah with various modifications, additions and clarifications added to these rules by halakha.

Leviticus 11:3–8 and Deuteronomy 14:4–8 both give the same general set of rules for identifying which land animals (Hebrew: בהמות Behemoth) are ritually clean.

Both documents explicitly list four animals as being ritually impure: While camels possess a single stomach, and are thus not true ruminants, they do chew cud; additionally, camels do not have hooves at all, but rather separate toes on individual toe pads, with hoof-like toenails.

Although not ruminants, hyraxes have complex, multichambered stomachs that allow symbiotic bacteria to break-down tough plant materials, though they do not regurgitate it for re-chewing.

[8] Further clarification of this classification has been attempted by various authors, most recently by Rabbi Natan Slifkin, in a book, entitled The Camel, the Hare, and the Hyrax.

[9] Unlike Leviticus 11:3-8, Deuteronomy 14:4-8 also explicitly names 10 animals considered ritually clean: The Deuteronomic passages mention no further land beasts as being clean or unclean, seemingly suggesting that the status of the remaining land beasts can be extrapolated from the given rules.

By contrast, the Levitical rules later go on to add that all quadrupeds with paws should be considered ritually unclean,[15] something not explicitly stated by the Deuteronomic passages.

The Leviticus passages thus cover all the large land animals that naturally live in Canaan, except for primates, and equids (horses, zebras, etc.

[19] Due to comparatively recent discoveries about the cultures adjacent to the Israelites, it has become possible to investigate whether such principles could underlie some of the food laws.

Egyptian priests would only eat the meat of even-toed ungulates (swine, camelids, and ruminants), and rhinoceros.

If one believes that religious customs are at least partly explained by the ecological conditions in which a religion evolves, then this too could account for the origin of these rules.

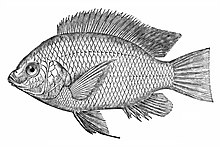

[35] These rules restrict permissible seafood to stereotypical fish, prohibiting the unusual forms such as the eel, lamprey, hagfish, and lancelet.

In addition, they exclude non-fish marine creatures, such as crustaceans (lobster, crab, prawn, shrimp, barnacle, etc.

A minor controversy arises from the fact that the appearance of the scales of swordfish is heavily affected by the ageing process—their young satisfy Nachmanides' rule, but when they reach adulthood they do not.

Nevertheless, Aaron Chorin, a prominent 19th-century rabbi and reformer, declared that the sturgeon was actually ritually pure, and hence permissible to eat.

[40] Nachmanides believed that the restrictions against certain fish also addressed health concerns, arguing that fish with fins and scales (and hence ritually clean) typically live in shallower waters than those without fins or scales (i.e., those that were ritually impure), and consequently the latter were much colder and more humid, qualities he believed made their flesh toxic.

In the Shulchan Aruch, 3 signs are given to kosher birds: the presence of a crop, an extra finger, and a gizzard that can be peeled.

Rather than vulture (gyps), the Vulgate has "milvus", meaning "red kite", which historically has been called the "glede", on account of its gliding flight; similarly, the Syriac Peshitta has "owl" rather than "ibis".

The conclusion of modern scholars is that, generally, ritually unclean birds were those clearly observed to eat other animals.

The first indication of this view can be found in the 1st century BC Letter of Aristeas, which argues that this prohibition is a lesson to teach justice, and is also about not injuring others.

[87] Such allegorical explanations were abandoned by most Jewish and Christian theologians after a few centuries, and later writers instead sought to find medical explanations for the rules; Nachmanides, for example, claimed that the black and thickened blood of birds of prey would cause psychological damage, making people much more inclined to cruelty.

Pigeons and doves are known to be kosher[91] based on their permissible status as sacrificial offerings in the Temple of Jerusalem.