Kraken

This description was followed in 1734 by an account from Dano-Norwegian missionary and explorer Hans Egede, who described the kraken in detail and equated it with the hafgufa of medieval lore.

[9] With time, "krake" have come to mean any severed tree stem or trunk with crooked outgrowths, in turn giving name to objects and tools based on such, notably for the subject matter, primitive anchors and drags (grapnel anchors) made from severed spruce tops or branchy bush trunks outfitted with a stone sinker,[8][9] known as krake, but also krabbe in Norwegian or krabba in Swedish (lit. 'crab').

[13] Swedish SAOB gives the translations of Icelandic kraki as "thin rod with hook on it", "wooden drag with stone sinker" and "dry spruce trunk with the crooked, stripped branches still attached".

[17] One of the earliest possible descriptions of the kraken, based on its iconography, is found on Swedish writer Olaus Magnus' famous map of Scandinavia from 1539, the Carta marina, featuring various illustrated sea-monsters.

[37][38] The Carta marina describes the two monsters as follows: B monstra duo marina maxima vnum dentibus truculentum, alterum cornibus et visu flammeo horrendum / Cuius oculi circumferentia XVI vel XX pedum mensuram continet[35] B two enormous sea monsters, one with ferocious teeth, the other with horns and a horrendous flaming gaze / The circumference of whose eye measures 16 or 20 feet What measurement Magnus referenced is unknown.

The first description of the kraken by name, then as "sciu-crak" (compare Norwegian: sjø-krake, [ʂøː-²kɾɑː.kə], "sea-krake"), was given by Italian writer Negri in Viaggio settentrionale (Padua, 1700), a travelogue about Scandinavia.

[49] Erik Pontoppidan (1753), who popularized the kraken to the world, noted that it was multiple-armed according to lore, and conjectured it to be a giant sea-crab, starfish or a polypus (octopus).

[55] Denys-Montfort (1801) published on two giants, the "colossal octopus" with the enduring image of it attacking a ship, and the "kraken octopod", deemed to be the largest organism in zoology.

[58][59] According to his Norwegian informants, the kraken's body measured many miles in length, and when it surfaced it seemed to cover the whole sea, further described as "having many heads and a number of claws".

[24][62][l][citation needed] Egede also made the aforementioned identification of krake as being the same as the hafgufa of the Icelanders,[20][48] though he seemed to have obtained the information indirectly from the medieval Norwegian treatise, the Speculum Regale (or King's Mirror, c. 1250).

[49] The King's Mirror does somewhat extensively reference maritime animal life, including: twenty-one whale species; six seal varieties; description of the walrus; ‘sea-hedges’; as well as the legendary likes of the merman, mermaid, and kraken.

[90] Pontoppidan wrote of a possible specimen of the krake, "perhaps a young and careless one", which washed ashore and died in 1680 near Alstahaug Church on the island of Alsta, Norway.

[citation needed] Pontoppidan did tentatively identify the kraken to be a sort of giant crab, stating that the alias krabben best describes its characteristics.

[106] Pontoppidan then declared the kraken to be a type of polypus (=octopus)[109] or "starfish", particularly the kind Gessner called Stella Arborescens, later identifiable as one of the northerly ophiurids[110] or possibly more specifically as one of the Gorgonocephalids or even the genus Gorgonocephalus (though no longer regarded as family/genus under order Ophiurida, but under Phrynophiurida in current taxonomy).

[114][117] This ancient arbor (admixed rota and thus made eight-armed) seems like an octopus at first blush[118] but with additional data, the ophiurid starfish now appears bishop's preferential choice.

[124][r][126][129] In the end though, Pontoppidan again appears ambivalent, stating "Polype, or Star-fish [belongs to] the whole genus of Kors-Trold ['cross troll'], ... some that are much larger, .. even the very largest ... of the ocean", and concluding that "this Krake must be of the Polypus kind".

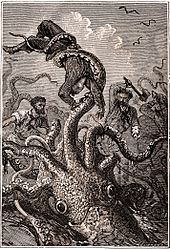

[105][131][s] In 1802, the French malacologist Pierre Denys de Montfort recognized the existence of two "species" of giant octopuses in Histoire Naturelle Générale et Particulière des Mollusques, an encyclopedic description of mollusks.

[146][143] It is in his chapter on the "colossal octopus" that Montfort provides the contemporary eyewitness example of a group of sailors who encounter the giant off the coast of Angola, who afterwards deposited a pictorial commemoration of the event as a votive offering at St. Thomas's chapel in Saint-Malo, France.

[158] The famous Swedish 18th-century naturalist Carl Linnaeus in his Systema Naturae (1735) described a fabulous genus Microcosmus a "body covered with various heterogeneous [other bits]" (Latin: Corpus variis heterogeneis tectum).

[145][159][160][t] Linnaeus cited four sources under Microcosmus, namely:[u][145][162] Thomas Bartholin's cetus (≈whale) type hafgufa;[164] Paullin's monstrum marinum aforementioned;[144] and Francesco Redi's giant tunicate (Ascidia[145]) in Italian and Latin.

[168][169][v][w] Also, the Frenchman Louis Figuier in 1860 misstated that Linnaeus included in his classification a cephalopod called "Sepia microcosmus"[x] in his first edition of Systema Naturae (1735).

Also, there was an alleged two-headed and horned monster that beached ashore in Dingle, County Kerry, Ireland, thought to be a giant cephalopod, of which there was a picture/painting made by the discoverer.

[citation needed] Ashton's Curious Creatures (1890) drew significantly from Olaus' work[190] and even quoted the Swede's description of the horned whale.

[200] This "Fortunate Island" was a destination on St. Brendan's Voyage, one of whose adventures was the landing of the crew on an island-sized monstrous fish,[ab] as depicted in a 17th-century engraving (cf.

As they fished, they saw some large mass floating before them, and upon further investigation, they discovered that the creature had a beak the size of a “six gallon keg”, tentacles greater in height than the two men, and the ability to spew ink when threatened.

It was not until Pierre Denys de Montfort's research on molluscs in the early 19th century that the octopus became established in Western culture as an archetype for the kraken.

[214][215][216][217] The French novelist Victor Hugo's Les Travailleurs de la mer (1866, "Toilers of the Sea") discusses the man-eating octopus, the kraken of legend, called pieuvre by the locals of the Channel Islands (in the Guernsey dialect, etc.).

[229] Kraken, also called the crab-fish, which is not that huge, for heads and tails counted, he is reckoned not to overtake the length of our Öland off Kalmar [i.e., 85 mi or 137 kilometres] ...

He stays at the sea floor, constantly surrounded by innumerable small fishes, who serve as his food and are fed by him in return: for his meal, (if I remember correctly what E. Pontoppidan writes,) lasts no longer than three months, and another three are then needed to digest it.

His excrements nurture in the following an army of lesser fish, and for this reason, fishermen plumb after his resting place ... Gradually, Kraken ascends to the surface, and when he is at ten to twelve fathoms [18 to 22 m; 60 to 72 ft] below, the boats had better move out of his vicinity, as he will shortly thereafter burst up, like a floating island, gushing out currnts like at Trollhättan [Trollhätteströmmar], his dreadful nostrils and making an ever-expanding ring of whirlpool, reaching many miles around.