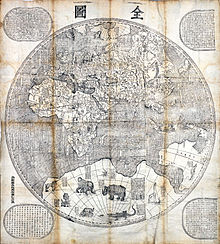

Kunyu Wanguo Quantu

The map's mirror image originally was carved on six large blocks of wood and then printed in brownish ink on six mulberry paper panels, similar to the making of a folding screen.

[2] Diane Neimann, a trustee of the James Ford Bell Trust, notes that: "There is some distortion, but what's on the map is the result of commerce, trade and exploration, so one has a good sense of what was known then.

"[2] Ti Bin Zhang, first secretary for cultural affairs at the Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., said in 2009: "The map represents the momentous first meeting of East and West" and was the "catalyst for commerce".

The brief description of North America mentions "humped oxen" or bison (駝峰牛 tuófēngníu), feral horses (野馬, yěmǎ), and names Canada (加拿大, Jiānádà).

Several Central and South American places are named, including Guatemala (哇的麻剌, Wādemálá), Yucatan (宇革堂, Yǔgétáng), and Chile (智里, Zhīlǐ).

"In olden days, nobody had ever known that there were such places as North and South America or Magellanica (using a name that early mapmakers gave to a supposed continent including Australia, Antarctica, and Tierra del Fuego), but a hundred years ago, Europeans came sailing in their ships to parts of the sea coast, and so discovered them.

During restoration and mounting, a central panel—a part of the Doppio Emisfero delle Stelle by the German mathematician and astronomer Johann Adam Schall von Bell—was inserted between the two sections by mistake.

[6] In 1938, an exhaustive work by Pasquale d'Elia, edited by the Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, was published with comments, notes, and translation of the whole map.

[7] The maps carry plentiful instructions for use and detailed illustrations of the instruments that went into their production, as well as explanations regarding conceptions of "systems of the terrestrial and celestial world".

D'Elia's translation reads: "Once I thought learning was a multifold experience and I would not refuse to travel [even] ten thousand Li to be able to question wise men and visit celebrated countries.

At the bottom left, in the Southern Hemisphere, is the name of the Chinese publisher of the map and the date: one day of the first month of autumn in the year 1602.

[9] Ricci had a small Italian wall map in his possession and created Chinese versions of it at the request of the governor of Zhaoqing at the time, Wang Pan, who wanted the document to serve as a resource for explorers and scholars.

[10] On January 24, 1601, Ricci was the first Jesuit - and one of the first Westerners - to enter the Ming capital Beijing,[6] bringing atlases of Europe and the West that were unknown to his hosts.

In 1602, at the request of the Wanli Emperor, Ricci collaborated with Mandarin Zhong Wentao, a technical translator, Li Zhizao,[9] and other Chinese scholars in Beijing to create what was his third and largest world map, the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu.

"According to John D. Day,[11] Matteo Ricci prepared four editions of Chinese world maps during his mission in China before 1603: Several prints of the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu were made in 1602.

The Vatican's 1602 copy was reproduced by Pasquale d'Elia in the beautifully arranged book, Il mappamondo cinese del P Matteo Ricci, S.I.

An unattributed and very detailed two page coloured edition of the map, known in Japanese as Konyo Bankoku Zenzu, was made in Japan circa 1604.

The Gonyeomangukjeondo (Hangul: 곤여만국전도) is a Korean hand-copied reproduction print by Painter Kim Jin-yeo in 1708, the 34th year of King Sukjong's rule of Joseon.

In the margins outside the ellipse, there are images of the northern and southern hemispheres, the Aristotelian geocentric world system, and the orbits of the Sun and Moon.

The map was then exhibited briefly at the Minneapolis Institute of Arts, before moving to its permanent home at the James Ford Bell Library at the University of Minnesota, where it has been on display since September 15, 2010.

[6] Hong Weilian,[13] earlier established a list of twelve total Ricci maps, which differs considerably from Day's findings.

(Descriptions of Foreign Land) His 1623 preface states that another Jesuit, Diego de Pantoja (1571–1618), on the command of the emperor, had translated a different European map, also following Ricci's model, but there is no other knowledge of that work.