Kutubiyya Mosque

[3] The minaret tower, 77 metres (253 ft) in height, is decorated with varying geometric arch motifs and topped by a spire and metal orbs.

[10] To the west and south of the mosque is a notable rose garden, and across Avenue Houmman-el-Fetouaki is the small mausoleum of the Almoravid emir Yusuf ibn Tashfin, one of the great builders of Marrakesh, consisting of a simple crenelated structure.

Also visible today at the northeast corner of these ruins and in other areas around the adjacent plaza are various remains attributed to the palace of Ali ibn Yusuf, built next to the fortress and completed in 1126, before being demolished by the Almohads to make way for their new mosque.

[18] While the Almohads decided to make Marrakesh their capital too, they did not want any trace of religious monuments built by the Almoravids, their staunch enemies, as they considered them heretics.

[6] As a result, Abd al-Mu'min decided to build the new mosque right next to the former Almoravid kasbah, the Ksar el-Hajjar, which became the site of the new Almohad royal palace, located west of the city's main square (what is today the Jemaa el-Fnaa).

[32][33] A more recent (2022) study by scholars Antonio Almagro and Alfonso Jiménez has argued for a reinterpretation of Arabic historical sources and proposes an alternative chronology.

It was closely associated with the ruling Almohad dynasty while also making subtle references to the ancient Umayyad caliphate in Cordoba, whose great mosque was a model for much of subsequent Moroccan and Moorish architecture.

[38] Almagro and Jiménez have argued that the remnants visible today belong to the first Almohad minaret and that it was built over a corner tower of the Almoravid fortress rather than a palace gate.

[3][9] The most popular historical narrative asserts that Abd al-Mu'min discovered, possibly during its construction, that the initial mosque was misaligned with the qibla (presumably according to Almohad criteria).

One historical source, originally written by Ibn Tufayl and reported by al-Maqqari, claims that Abd al-Mu'min began construction on a mosque in May 1158 (Rabi' al-Thani 553 AH) and that it was completed with the inauguration of the first Friday prayers in September (Sha'ban) of the same year.

[3] According to French scholar Gaston Deverdun and some later historians, the most likely scenario is that the minaret was begun before 1158 and largely built by Abd al-Mu'min, or at the very least designed on his commission.

[43] Deverdun, in his 1959 study of Marrakesh, suggested the possibility that the first mosque was only abandoned after Ya'qub al-Mansur built the new Kasbah, or royal citadel, further south.

[30] They suggest that in the second half of the 17th century, when the Saadi dynasty's power collapsed and Marrakesh underwent a period of decline, the mosque was neglected and fell into disrepair.

[30] Based on stylistic grounds, Almagro and Jimnez argue that the mosque's ornate wood ceilings (particularly over the central nave) date to sometime in the 'Alawi period and after the 17th century, most likely during an 18th-century restoration.

[71] The tower's prominence makes it a landmark structure of Marrakesh, which is maintained by an ordinance prohibiting any high rise buildings (above the height of a palm tree) to be built around it.

[72][1] The surface of the tower once featured polychrome decoration that was painted onto a mortar or plaster coating, highlighting some of the blind arches, niches, and spandrels.

[74] Forming a mosaic with a simple geometric pattern, this tilework is cited by Jonathan Bloom as the earliest reliably-dated example of zellij in Morocco.

[78][76] One version of the legend claims that there were at one time only three of them and that the fourth was donated by the wife of Yaqub al-Mansur as penance for breaking her fast for three hours one day during Ramadan.

[12][79] Another version of the legend is that the balls were originally made entirely of gold fashioned from the jewellery of the wife of Saadi Sultan Ahmad al-Mansur.

[82] Some of the surfaces of the walls inside the minaret are also carved with various graffiti in the form of architectural and decorative patterns, possibly left behind by artisans and architects who worked on the mosque over many years.

[83] The Kutubiyya Mosque's original minbar (pulpit) was commissioned by Ali ibn Yusuf, one of the last Almoravid rulers, and created by a workshop in Cordoba, Spain (al-Andalus).

[1][80] Its artistic style and quality was hugely influential and set a standard which was repeatedly imitated, but never surpassed, in subsequent minbars across Morocco and parts of Algeria.

[35] It is believed that the minbar was originally placed in the first Ben Youssef Mosque (named after Ali ibn Yusuf, but entirely rebuilt in later centuries).

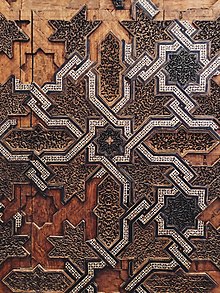

The large triangular faces of the minbar on either side are covered in an elaborate and creative motif centered around eight-pointed stars, from which decorative bands with ivory inlay then interweave and repeat the same pattern across the rest of the surface.

The spaces between these bands form other geometric shapes which are filled with panels of deeply-carved arabesques, made from different coloured woods (boxwood, jujube, and blackwood).

[35] There is a 6 centimetres (2.4 in) wide band of Quranic inscriptions in Kufic script on blackwood and bone running along the top edge of the balustrades.

Notably, the steps of the minbar are decorated with images of an arcade of Moorish (horseshoe) arches inside which are curving plant motifs, all made entirely in marquetry with different colored woods.

[35] Historical accounts describe a mysterious semi-automated mechanism in the Kutubiyya Mosque by which the minbar would emerge, seemingly on its own, from its storage chamber next to the mihrab and move forward into position for the imam's sermon.

[35] This mechanism, which elicited great curiosity and wonder from contemporary observers, was designed by an engineer from Malaga named Hajj al-Ya'ish, who also completed other projects for the caliph.

Modern archaeological excavations carried out on the first Kutubiyya Mosque have found evidence confirming the existence of such a mechanism, though its exact workings are not fully established.