Zellij

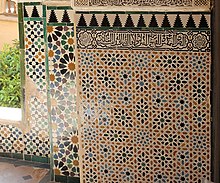

Zellij (Arabic: زليج, romanized: zillīj), also spelled zillij or zellige, is a style of mosaic tilework made from individually hand-chiseled tile pieces.

[10][11] In Spain, the mosaic tile technique used in historical Islamic monuments like the Alhambra is also referred to as alicatado, a Spanish word deriving from the Arabic verb qata'a (ﻗَﻄَﻊَ) meaning "to cut".

[12][3]: 166 Zellij fragments from al-Mansuriyya (Sabra) in Tunisia, possibly dating from either the mid-10th century Fatimid foundation or from the mid-11th Zirid occupation, suggest that the technique may have developed in the western Islamic world around this period.

[5] Georges Marçais argued that these fragments, along with similar decoration found at Mahdia, indicate that the technique likely originated in Ifriqiya and was subsequently exported further west.

[4][6]: 28 By the 11th century, the zellij technique had reached a sophisticated level in the western Islamic world, as attested in the elaborate pavements found at the Hammadid capital, Qal'at Bani Hammad, in Algeria.

Found in palaces built between 1068 and 1091, these might be attributable to Ifriqiyan craftsmen who fled the Banu Hilal invasions to the east and sought refuge with the Hammadids around this time,[13] though the lustre tiles may have been imported from elsewhere.

[1]: 231 Jonathan Bloom cites the glazed tiles on the minaret of the Kutubiyya Mosque, dating from the mid-12th century, as the earliest reliably-dated example of zellij in Morocco.

Each piece was pierced with a small hole prior to being baked so that the tiles could be affixed by nails to a wooden frame set into a mortar surface on this part of the minaret.

[15]: 326–333 The more complex zellij style that we know today became widespread during the first half of the 14th century under the Marinid, Zayyanid, and Nasrid dynastic periods in Morocco, Algeria, and al-Andalus.

[1]: 335–336 [16] Due to the significant cultural unity and relations between al-Andalus and the western Maghreb, the forms of zellij under Marinid, Nasrid, and Zayyanid patronage are extremely similar.

[3]: 188–189 In Ifriqiya (Tunisia), under the Hafsid dynasty, zellij tiling largely fell out of style during this same period and was replaced by a preference for stone and marble paneling.

It is also found in some Christian Spanish palaces of the same period who employed Muslim or Mudéjar craftsmen, most notably the Alcazar of Seville, whose 14th-century sections are contemporary with the Alhambra and contain zellij tilework in the same style, although of slightly lesser sophistication.

[20]: 178 Today, the archaeological museum of Tlemcen contains many remains of panels and fragments of zellij from various medieval monuments dating back to the Zayyanid dynasty.

[21] The epigraphic friezes in Marinid tilework, which typically topped the main mosaic dadoes, were made through a different technique known more widely as sgraffito (from the Italian word for "scratched"[22]).

In Algeria, the indigenous zellij style was mostly supplanted by small square tiles imported from Europe – especially from Italy, Spain, and Delft – and sometimes from Tunis.

[8]: 102 Towards the late 15th and early 16th centuries Seville became an important production center for a type of tile known as cuenca ("hollow") or arista ("ridge").

[17]: 64–65 [8]: 102 [26] The motifs on these tiles imitated earlier Islamic and Mudéjar designs from the zellij mosaic tradition or blended them with contemporary European influences such as Gothic or Italian Renaissance.

[1]: 415 Over the centuries since the Saadi period, the sgraffito technique previously used for Marinid epigraphic friezes came into more general usage in Morocco as a simpler and more economic alternative to mosaics.

[31] The exception to this is the city of Tétouan (in northern Morocco), which since the 19th century has hosted its own mosaic zellij industry employing a technique differing from that of Fez.

[2]: 41 Zellij tiles are first fabricated in glazed squares, typically 10 cm per side, then cut by hand with a small adze-like hammer into a variety of pre-established shapes (usually memorized by rote learning) necessary to form the overall pattern.

[2]: 41–43 The small shapes (cut according to a precise radius gauge) of different colours are then assembled in a geometrical structure as in a puzzle to form the completed mosaic.

This results in a harder enamel that lasts longer, but the colours are not as bright and the tile pieces generally do not fit together as tightly as those produced in other cities like Fez.

[15]: 563 [6]: 33 In the case of the Almohad tilework on the minarets of the Kutubiyya and Kasbah Mosque in Marrakesh, the tiles were nailed to a wooden framework set into the surface of the wall behind them.

[5] Geometric patterns were created on the basis of tessellation: the method of covering a surface with the use of forms that can be repeated and fitted together without overlapping or leaving empty spaces between them.

[5][34][35] In western Islamic art, under the Nasrid and Marinid dynasties, a great variety of geometric patterns were created for architectural decoration.

[33]: 110 Some exceptional examples of this pattern from the Marinid period are found in the zellij tilework of the al-Attarine and Bou Inania madrasas in Fez, where greater visual diversity was once again achieved by using large repeating units.

[6] Yet another motif consists of one repeating curvilinear form resembling a double-headed axe, which is found in the Alhambra and is also common in the zellij of Tétouan in Morocco, where it is known in Arabic as the "four hammers" (arba'a matariq).

[36]Islamic decoration and craftsmanship had a significant influence on Western art when Venetian merchants brought goods of many types back to Italy from the 14th century onwards.

[41][additional citation(s) needed] In Morocco, Fez is still a production center for zellīj tiles due in part to the Miocene grey clay found in the area.

[42] A study by Meriam El Ouahabi, L. Daoudi, and Nathalie Fagel states that: From the other sites (Meknes, Fes, Salé and Safi), the clay mineral composition shows besides kaolinite the presence of illite, chlorite, smectite and traces of mixed layer illite/chlorite.