L'Africaine

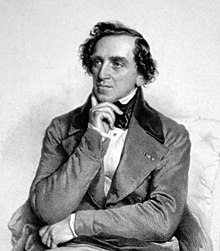

L'Africaine (The African Woman) is an 1865 French grand opéra in five acts with music by Giacomo Meyerbeer and a libretto by Eugène Scribe.

The opera was premiered the following year by the Paris Opéra in a version made by François-Joseph Fétis, who restored the earlier title, L'Africaine.

The starting point for the story was "Le Mancenillier", a poem by Charles Hubert Millevoye, in which a girl sits under a tree releasing poisonous vapors but is saved by her lover.

[1] The plot is also based on an unidentified German tale and a 1770 play by Antoine Lemierre, La Veuve de Malabar, in which a Hindu maiden loves a Portuguese navigator, a theme already treated by the composer Louis Spohr in his opera Jessonda.

The loss of Falcon and reservations about the libretto caused Meyerbeer to set the project aside in the summer of 1838, when he shifted his focus to the preparation of Le Prophète.

While sailing for Mexico in Act 3, his ships are forced to seek shelter on the coast of Sélika's kingdom in Africa on the Niger River.

Meyerbeer had read a French translation of Camoens's The Lusiads, an epic poem that celebrates the discovery of a sea route to India by Vasco da Gama.

[9] The music historian Robert Letellier has written that Fétis "on the whole reached an acceptable compromise between the presumed artistic wishes of Meyerbeer and the practical necessities of performance", but "retaining the historical figure of Vasco, as well as the Hindu religion depicted in Act 4, led to almost irreparable absurdity in the action because of the change in locations given for Acts 4 and 5 on the printed libretto in the vocal score (an island on the east coast of Africa) and in the full score (an island in the Indian archipelago).

[10][11] Tim Ashley of The Guardian wrote: Fétis's alterations consisted largely of cuts and re-orderings, the aim of which, ostensibly, was to bring the opera within manageable length, and to improve narrative clarity, though the plot, by operatic standards, isn't that difficult.

[12]The opera was premiered on 28 April 1865 by the Opéra at the Salle Le Peletier in Paris under the title L'Africaine in the performing edition undertaken by Fétis.

[13] Because of the long-running and unprecedented advance publicity, including countless reports in the domestic and international press, the production was a social and artistic sensation.

The first night, attended by Emperor Napoleon III and Empress Eugénie, "provided Second Empire society with its most exalted self-presentation in terms of an opera premiere.

A bust of the composer, newly executed by Jean-Pierre Dantan, was revealed on the stage at the conclusion of the performance, and with only a few exceptions critics declared the production brilliant and the opera, Meyerbeer's masterpiece.

In its first year it brought in 11,000 to 12,000 francs per performance (roughly twice what was earned by other programs) and reached its 100th presentation at the Salle Le Peletier on 9 March 1866.

It was given there 225 times before its first performance in a new production at the new Paris opera house, the Palais Garnier, on 17 December 1877, and reached 484 representations before it was dropped from the repertoire on 8 November 1902.

Plácido Domingo has sung it in at least two productions: a revival at the War Memorial Opera House in San Francisco that premiered on November 13, 1973, with Shirley Verrett; and in 1977 at the Liceu in Barcelona, with Montserrat Caballé.

[20] This edition was also used for a production at the Deutsche Oper in October 2015, with Roberto Alagna as Vasco de Gama and Sophie Koch as Sélika.

It also restores much of the original material that Fétis and his collaborators had altered in preparation both for the first performance and for the first publication of the work by G. Brandus & S. Dufour (1865).

The prison Sélika, who is in fact queen of the undiscovered land, saves de Gama, whom she loves, from being murdered by Nélusko, a member of her entourage.

Possibly because of advance publicity and high expectations, the Shipwreck Scene of act 3, executed by numerous stagehands, was deemed by the press to be somewhat disappointing.

[34] Lynn René Bayley, writing in Fanfare commented on this recording: "I was so angered by this performance I could almost spit nails, because neither the conductor nor the cast understand Meyerbeer style in the slightest.