LZ 127 Graf Zeppelin

It was built using funds raised by public subscription and from the German government, and its operating costs were offset by the sale of special postage stamps to collectors, the support of the newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst, and cargo and passenger receipts.

[5] In 1917, the German LZ 104 (L 59) was the first airship to make an intercontinental flight, from Jambol in Bulgaria to Khartoum and back, a nonstop journey of 6,800 kilometres (4,200 mi; 3,700 nmi).

Eckener saw an opportunity to start an intercontinental air passenger service,[12] and began lobbying the government for funds and permission to build a new civil airship.

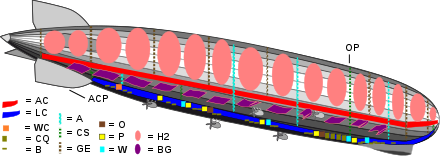

[33] Graf Zeppelin was powered by five Maybach VL II 12-cylinder 410 kW (550 hp) engines, each of 33.251 L (2,029.1 cu in) capacity, mounted in individual streamlined nacelles[nb 5] arranged so that each was in an undisturbed airflow.

[51][52][nb 8] The ship flew in with its nose trimmed slightly down, made its final approach into the wind descending at 30 m (100 ft) per minute, then used reverse thrust to stop over the landing flag, where it dropped ropes to the ground.

Two 8.9 kW (12 hp) Wanderer car engines adapted to burn Blau gas, only one of which operated at a time, drove two Siemens & Halske dynamos each.

[74] Two ram air turbines attached to the main gondola on swinging arms provided electrical power for the radio room, internal lighting, and the galley.

Passengers paid premium fares to fly on the Graf Zeppelin (1,500 ℛ︁ℳ︁ from Germany to Rio de Janeiro in 1934, equal to $590 then,[79] or $13,000 in 2018 dollars[15]), and fees collected for valuable freight and air mail also provided income.

[83] He took complete responsibility for the ship, from technical matters, to finance, to arranging where it would fly next on its years-long public relations campaign, in which he promoted "zeppelin fever".

[86] Eckener cultivated the press, and was gratified when the British journalist Lady Grace Drummond-Hay wrote, and millions read, that: The Graf Zeppelin is a ship with a soul.

[90] On one visit to Rio de Janeiro people released hundreds of small toy petrol-burning hot air balloons near the flammable craft.

[92] On visits to England, it photographed Royal Air Force bases, the Blackburn aircraft factory in Yorkshire, and the Portsmouth naval dockyard; it is likely that this was espionage at the behest of the German government.

Graf Zeppelin carried Oskar von Miller, head of the Deutsches Museum; Charles E. Rosendahl, commander of USS Los Angeles; and the British airshipmen Ralph Sleigh Booth and George Herbert Scott.

It flew from Friedrichshafen to Ulm, via Cologne and across the Netherlands to Lowestoft in England, then home via Bremen, Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig and Dresden, a total of 3,140 kilometres (1,950 mi; 1,700 nmi) in 34 hours and 30 minutes.

[94] On the fifth flight, Eckener caused a minor controversy by flying close to Huis Doorn in the Netherlands, which some interpreted as a gesture of support for the former Kaiser Wilhelm II who was living in exile there.

[95][96] In October 1928, Graf Zeppelin made its first intercontinental trip, to Lakehurst Naval Air Station, New Jersey, US, with Eckener in command and Lehmann as first officer.

[120][121] American newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst's media empire paid half the cost of the project to fly Graf Zeppelin around the world,[122] with four staff on the flight: Lady Hay Drummond-Hay, Karl von Wiegand, Australian explorer Hubert Wilkins, and cameraman Robert Hartmann.

After five days at a former German airship shed that had been removed from Jüterbog and rebuilt at Kasumigaura Naval Air Station,[129][130] Graf Zeppelin continued across the Pacific to California.

[126] On 26 April 1930, Graf Zeppelin flew low over the FA Cup Final at Wembley Stadium in England, dipping in salute to King George V, then briefly moored alongside the larger R100 at Cardington.

[146][147] The Europe-Pan American flight was largely funded by the sale of special stamps issued by Spain, Brazil, and the US for franking mail carried on the trip.

Graf Zeppelin crossed the Mediterranean to Benghazi in Libya, then flew via Alexandria, to Cairo in Egypt, where it saluted King Fuad at the Qubbah Palace, then visited the Great Pyramid of Giza and hovered 20 m (66 ft) above the top of the monument.

The costs of the expedition were met largely by the sale of special postage stamps issued by Germany and the Soviet Union to frank the mail carried on the flight.

[174] Graf Zeppelin made 64 round trips to Brazil, on the first regular intercontinental commercial air passenger service,[176] and it continued until the loss of the Hindenburg in May 1937.

[177][178] When the Nazis gained power in 1933, Joseph Goebbels (Reich Minister of Propaganda) and Hermann Göring (Commander-in-chief of the Luftwaffe) sidelined Eckener by putting the more sympathetic Lehmann in charge of a new airline, Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei (DZR), which operated German airships.

[181] They toured the country for four days and three nights, dropping propaganda leaflets, playing martial music and slogans from large loudspeakers, and broadcasting political speeches from a makeshift radio studio on Hindenburg.

[182] The crew heard of the Hindenburg disaster by radio on 6 May 1937 while in the air, returning from Brazil to Germany; they delayed telling the passengers until after landing on 8 May so as not to alarm them.

[183][184] The disaster, in which Lehmann and 35 others were killed, destroyed public faith in the safety of hydrogen-filled airships, making continued passenger operations impossible unless they could convert to non-flammable helium.

[178][190] President Roosevelt supported exporting enough helium for the Hindenburg-class LZ 130 Graf Zeppelin II to resume commercial transatlantic passenger service by 1939,[191] but by early 1938, the opposition of Interior Secretary Harold Ickes, who was concerned that Germany was likely to use the airship in war, made that impossible.

"[192][193] Graf Zeppelin II made 30 test, promotional, propaganda and military surveillance flights around Europe using hydrogen between September 1938 and August 1939; it never entered commercial passenger service.

[78] By the time the two Graf Zeppelins were recycled, they were the last rigid airships in the world,[199] and heavier-than-air long-distance passenger transport, using aircraft like the Focke-Wulf Condor and the Boeing 307 Stratoliner, was already in its ascendancy.