La Silva Curiosa

The 1608 edition holds significance for Cervantes collectors and scholars as it features an early printing of his Novela del Curioso Impertinente, a narrative later recounted in Don Quixote and first published in 1605.

Queen Margaret, as attested by Pierre de Bourdeille, Lord of Brantôme, possessed a proficiency in Spanish and Italian as if she had been nurtured and immersed in Italy and Spain throughout her life.

[3] In the beginning of La Silva Curiosa, Medrano addresses the reader directly with two octaves: Here, the keen mind may find a way to lighten the heaviest, dreariest hours, to pass the time in joy and in play, in this garden of sweet and delightful flowers.

Here one may behold divine things, indeed, a keen, lofty style, grave and resounding, words of love, in folly and reason, and twenty thousand secrets of nature surrounding.

[1] According to Mercedes Alcalá Galán (1998: 10-11): [La Silva Curiosa] embodies all the generic principles applicable to miscellanies and is particularly notable for its wholly literary and fictional content.

The use of the garden metaphor, with its diverse flowers symbolizing a miscellany, reflects an intent for entertainment and a certain freedom in composition, suggesting an improvisational approach to writing.

ABOUT THE CURIOUS FOREST OF DE MEDRANE: Let whoever wishes boast about Apelles, Zeuxis, Lisippus, and those closer to our time, Raphael, Michelangelo, and so many experts in their proportions, shading, and variegation.

[3] It cites well-known authors and others who are not so much so: "Antonio Miraldo, Alifarnes, Avicenna, Aristotle, Aeliano, Amato Lusitano, Andrea Matheolo, Fray Alonso del Castillo, St. Augustine, Democritus, Dioscorides, Galen, Plutarch, Peter Messiah, Ptolemy, St. Thomas, but not in others because he is usually a liar, Albert the Great in certain steps, but not in all because he says so much nonsense and lies, Sant Cristobal Navarre, great philosopher and astrologer, the Hermit of Salamanca, very rare in secrets and experiences, above all the friars and hermits of his time, and in the Secrets of Nature very speculative, curious and excellent.

Notable instances include the accounts of the witch Orcavella and a hermitage famulus who divulges forbidden book secrets and the manipulation of a magic mirror.

Woven into the broader narrative, the protagonist Julián Íñiguez de Medrano ("Julio") embarks on a journey from Roncesvalles to the Indies, albeit the details of this segment remain untold.

The journey encompasses pilgrimages to Santiago de Compostela and Finisterre, Medrano intricately interlaces tales and compositions, presenting them to Queen Margarita and the inquisitive reader.

[3] The first book of La Silva curiosa ("The Curious Forest"), the only one still readable, is a set of letters, mottoes, sayings, proverbs, moral sentences, verses...

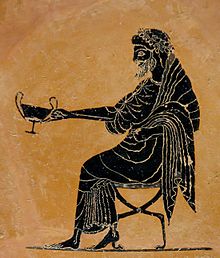

Palindromes, such as "To the only Rome, Love to los solos sola," enigmas like the intricate one involving a eunuch striking a bat on an elder tree with a rough stone, and goliardic parodies, including a humorous prayer to Bacchus ("Potemus.

The peculiar dining ritual involves breaking the trout into pieces, and each participant, in their pursuit of a portion, must recite a Bible passage related to the chosen part.

Julián Íñiguez de Medrano explains himself that he is "returning to women, and desiring that they may know the great reverence with which I hold the name of woman, and that, leaving the path of ungrateful and harmful slanderers, I strive to elevate and praise this creature to the highest heaven (since nature in its generation made her so noble, and among all creatures, she emerged so perfect) in return for the many obligations we men owe them, as we are born of them, die without them, live in them, and we couldn't preserve or endure without them.

[21] The National Library of Paris holds a small work in whose exact title is as follows: "RELATION OF THE DISCOVERY OF THE TOMB OF THE ENCHANTRESS ORCAVELLE WITH THE TRAGIC HISTORY OF HER LOVES.

[22] Lara Alberola argues that De Castera's Relation transforms Orcavella into a Gothic antihero and heightens horror elements, making her a supernatural figure depicted through her own voice.

Alberola believes that the adaptation shifts from Medrano’s detached storytelling in the Silva Curiosa, where Orcavella’s tale was relayed by a Galician shepherd, to an introspective Gothic style.

She asserts that by claiming to translate a “lost manuscript,” De Castera may have used a narrative device to add mystery and authenticity, positioning the Relation as a precursor to Gothic fiction.

[22] Furthermore, he provides interesting but difficult-to-verify information about Medrano's works: "He has two books to his name, with the titles 'Verger fertile' and 'Fóret curieuse,' both of which have had various editions, followed by general acclaim both in France and Spain".

The following clarification by de Castera states: "The latter has never been printed; I found the manuscript written by Médrane himself in the illustrious Abbey of Châtillon, where, in the intervals of leisure that more serious studies allowed me, I amused myself by adapting it in a French manner.

[22] Castera becomes the narrator of the events that happened to Medrano, who is thus described in the third person: Jule Iniguez de Médrano, a Navarrese gentleman, illustrious for his knowledge and celebrated for his travels throughout almost the entire world, recounts that one day, while sitting near Mount Caucasus on a grassy hill, he felt that the grass beneath him was sinking.

This manuscript, which according to De Castera, Medrano claims to have found in a tomb, and contains a confession, in the first person, of a witch named Orcavella, who, after briefly evoking her life as a fat collector, ogress, and vampire, relates the sad story of her love.

From there, it could be a faithful translation of Medrano's text, as what precedes clearly corresponds to an account attributable to De Castera, drawing inspiration from the manuscript found in the Abbey of Châtillon and elements from the second part of the Silva Curiosa.

[22] It was Queen Margaret of Valois, eager to read texts in Spanish that commissioned Medrano to write La silva curiosa, the work that she would pass on to posterity.

Just as the good gardener, after patiently enduring the cruel cold of winter (and often toiling amidst the snow and harsh ice, consoled only by the hope that one day he will savor the flowers and delicious fruit promised by nature in reward for his tireless labor in tending to his garden), and one day, at the beginning of spring, while digging and tilling among thorns and vexing weeds, uncovers in a corner a blooming rose, he receives such a stroke of good fortune and immense joy that, forgetting past toils, he tosses his spade to the ground, rushes to seize it, and, with great delight, kisses it and blesses the Lord who created it.

In a similar way, I, Most High and Serene Lady (being a native of Navarre and recognizing that the greater part of the honor, being, and fortune I possess, next to God, springs and proceeds from Your Majesty as the true source of my happiness and life), have found this first and tender flower of my labors among the thorns of my sorrows and toils.

Though this gift may be small, the giver's spirit is great, and I will strive in the future to create something of greater value than this work, which I have divided into seven books due to their diverse subject matter.

If in this first book Your Majesty enjoys the flowers, in the subsequent ones, you will savor the delicious fruit of the rarest and most curious secrets of nature that I have been able to learn and gather from Spain, the Indies, and my interactions with Italians and Portuguese.

For I recognize that my language is inept, my style coarse, and my intellect feeble and extremely weak to praise a soul as beautiful and divine (enclosed in a body endowed with so many gifts of nature) as Your Majesty.