Great Railroad Strike of 1877

Because of economic problems and pressure on wages by the railroads, workers in numerous other states, from New York, Pennsylvania and Maryland, into Illinois and Missouri, also went out on strike.

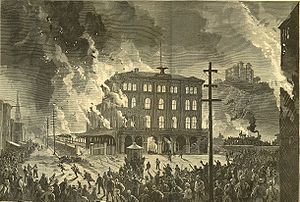

In Martinsburg, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia and other cities, workers burned down and destroyed both physical facilities and the rolling stock of the railroads—engines and railroad cars.

Fearing future social disruption, many cities built armories to support local National Guard units; these defensive buildings still stand as symbols of the effort to suppress the labor unrest of this period.

With public attention on workers' wages and conditions, the B&O in 1880 founded an Employee Relief Association to provide death benefits and some health care.

By 1877, 10 percent wage cuts, distrust of capitalists and poor working conditions led to workers conducting numerous railroad strikes that prevented the trains from moving, with spiraling effects in other parts of the economy.

But by the late 19th century, the Knights of Labor (KOL), a national and predominately European and Catholic organization, had 700,000 members seeking to represent all workers.

[9] The strike began when Baltimore & Ohio (B&O) Railroad president John W. Garrett cut wages by ten per cent to increase dividends by the same percentage.

The Sixth assembled at its armory at East Fayette and North Front Streets (by the old Phoenix Shot Tower) in the Old Town /Jonestown area and headed to Camden.

It was a horrible scene reminiscent of the worst of the bloody "Pratt Street Riots" of the Civil War era in April 1861, over 15 years earlier.

Some protestors acted out of solidarity with the strikers, but many more vented militant displeasure against dangerous railroad traffic that crisscrossed urban centers in that area.

Thomas Alexander Scott of the Pennsylvania Railroad, described as one of the first robber barons, suggested that the strikers should be given "a rifle diet for a few days and see how they like that kind of bread".

Strikers set fires that razed 39 buildings and destroyed rolling stock, including 104 locomotives and 1,245 freight and passenger cars.

After more than a month of rioting and bloodshed in Pittsburgh, President Rutherford B. Hayes sent in federal troops as in West Virginia and Maryland to end the strikes.

Three hundred miles to the east, Philadelphia strikers battled local National Guard units and set fire to much of downtown before Pennsylvania Governor John Hartranft gained assistance and federal troops from President Hayes to put down the uprising.

Preludes to the massacre included fresh work stoppage by all classes of the railroad's local workforce, mass marches, blocking of rail traffic, and trainyard arson.

Workers burned down the only railroad bridge offering connections to the west, in order to prevent local National Guard companies from being mustered to actions in the state capital of Harrisburg or Pittsburgh.

[19] On July 25, 1,000 men and boys, many of them coal miners, marched to the Reading Railroad Depot in Shamokin, east of Sunbury along the Susquehanna River valley.

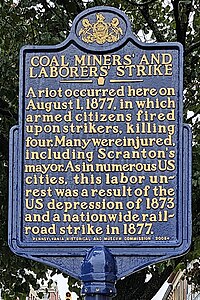

[21][22] Pennsylvania Governor Hartranft declared Scranton to be under martial law; it was occupied by state and federal troops armed with Gatling guns.

Judge Thomas Drummond of the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit, who was overseeing numerous railroads that had declared bankruptcy in the wake of the earlier financial Panic of 1873, ruled that, "A strike or other unlawful interference with the trains will be a violation of the United States law, and the court will be bound to take notice of it and enforce the penalty".

Marshals to protect the railroads and asked for federal troops to enforce his decision; he subsequently had strikers arrested and tried them for contempt of court.

An estimated 20 men and boys died, none of whom were law enforcement or troops; scores more were wounded, and the loss of property was valued in the millions of dollars.

On July 21, workers in the industrial rail hub of East St. Louis, Illinois, halted all freight traffic, with the city remaining in the control of the strikers for almost a week.

The St. Louis Workingman's Party led a group of approximately 500 men across the Missouri River in an act of solidarity with the nearly 1,000 workers on strike.

[25] The strike on both sides of the river was ended after the governor appealed for help and gained the intervention of some 3,000 federal troops and 5,000 deputized special police.

When news of the strikes reached the west coast, the Central Pacific Railroad rescinded its 10 percent wage cut, but this did not prevent the type of worker unrest seen in the east.

Despite attempts by the organizers to focus the crowd's energy against the railroad monopolies, the rally soon turned to a riot against the local Chinese population.

Despite the strike not resulting in an immediate acceptance of worker demands, over the next several years many railroads restored all or part of the initial pay cuts and were reluctant to put further pressure on wages.

[36][37]: 118 After the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, union organizers planned for their next battles while politicians and business leaders took steps to prevent a repetition of this chaos.

[citation needed] In response to the Great Strike, West Virginia Governor Henry M. Mathews was the first state commander-in-chief to call up militia units to restore peace.

[42] Attempts to utilize the National Guard to quell violent outbreaks in 1877 highlighted its ineffectiveness, and in some cases its propensity to side with strikers and rioters.