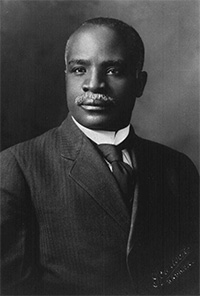

Lafayette M. Hershaw

He was a leader of the intellectual social groups in the capital such as Bethel Literary and Historical Society and the Pen and Pencil Club.

[4][page needed] He had three daughters, Rosa Cecile (who married James T. W. Granady, Howard alum and Harlem, New York doctor), Alice May, and Fay M.[1] Charlotte died on October 26, 1930.

[5] Hershaw died September 2, 1945, in the Freedmen's Hospital in Washington D.C. His funeral was at the Plymouth Congregational Church and he was buried in Lincoln Memorial Cemetery.

While this bill was supported by some black leaders, including AME bishop Henry McNeal Turner, Hershaw was very vocal against it.

This speech offended Colonel W. S. Thompson and Judge William Roberson Hammond of the Board of Education in the City of Atlanta, and the pair had Hershaw fired.

[10] He responded that he did support the president and the Republican Party, and believed Roosevelt stood for justice, civil equality, and fair play.

[11] While not campaigning for Roosevelt, he did travel the country with fellow federal employee Judson Whitlocke Lyons to speak at republican events in October 1904.

In 1925, Hershaw was promoted to Assistant Law Examiner, the highest position held up to that time by a black man in the Land Office.

This outlined Washington's conservative approach and came to represent a compromise in the South of black education and due process in exchange for white political rule.

[17] Other government workers: A. E. Clark (society president and clerk at the Pension Office), Jesse Lawson (also a clerk at the Pension Office and editor of The Colored American, Washington, D.C., and John Wesley Cromwell also endorsed the speech while non-government workers condemned it; leading to criticism of supporters of Washington for apparent willingness to support compromise so that they do not put their jobs at risk.

In an editorial reply, Charles Remond Douglass saw the argument as similar to those of Booker T. Washington that black people must show through their achievements that they deserve their position in civilization.

[20] After a few more editorials, Douglass recognized that the remainder of Miller's address clarified the issue and the real problem lay in the excerpt by the newspaper, The Washington Post, which only included the offensive paragraph that minimized the value of blacks.

In 1892 he spoke in front of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society, giving a talk on January 12 on, "Protection and its relation to the American Negro".

[24] He became a regular attendee of meetings and, as mentioned above, played an important dissenting role in criticism of Booker T. Washington by the group in 1895.

[22] Hershaw also led the society to support calls for civil service reform made by Robert H. Terrell, who presented on the subject in June 1897.

[31] In 1902, Hershaw stepped down as president in favor of Henry P. Slaughter who was followed by Arthur S. Gray but continued to be a prominent member and a prolific speaker at the clubs events.

Du Bois famous line that "the problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line" before presenting an argument that hews closely to the ideas of Du Bois: the equality of blacks and whites, the importance of political and civil equality rather than simply industrial opportunity, the illegitimacy of "Jim Crow Cars", and against compromise.

[34] As a prominent member of D.C. literary and activist circles, Hershaw frequently presented papers and speeches regarding the sociology, economics, and history of Blacks.

[35] On the last night of the conference, Hershaw delivered a speech written by Du Bois called, "Address to the Country", which was extremely well received.

The meeting was welcomed by Storer College president Henry T. McDonald and was marked by reports by Niagara Movement state secretaries.

Hershaw's speech, as well as that of C. E. Bently, George W. Mitchell, Byron Gunner, O. M. Waller, and C. G. Morgan were noted as especially strong.

[4] The journal was published from 1907 to 1910; Murray was printer and Du Bois and Hershaw were co-editors[14] W. M. Sinclair and William Monroe Trotter were noted as other key players in the movement and involved in the magazine.

[51] Hershaw played a key role in Waldron's removal[52] and the smooth transition of the branch to the presidency of Archibald Grimké, who held the position until 1925.

Branch Executive Committee under president Archibald Grimké and worked in support of the cause of Sergeant Edgar Caldwell, who shot a white man in self-defense in Anniston, Alabama.

[53] In 1919, NAACP head Walter Francis White asked James A. Cobb to work to prevent the execution of Caldwell.

Cobb arranged a meeting with Assistant Attorney General Harry Steward and brought with him Emmett Jay Scott, Caldwell's lawyer Charles Kline, Hershaw, and William Houston.

[51] Also in 1919, Hershaw along with Henry Lassiter, Walter J. Singleton, Archibald Grimké, and Robert H. Terrell was a prime mover in the introduction by Congressman Martin B. Madden of a law to abolish the "Jim Crow" car.

The Bee writer criticized Henshaw for taking such a large federal salary[57] and as a member of the Bethel Literary and Historical Society for being elitist.

[68] In 1907 he was elected head of the newspaper bureau of the National Afro-American Council[69] which quickly disappeared as members joined the Niagara Movement.