Lake ecosystem

Over long periods of time, lakes, or bays within them, may gradually become enriched by nutrients and slowly fill in with organic sediments, a process called succession.

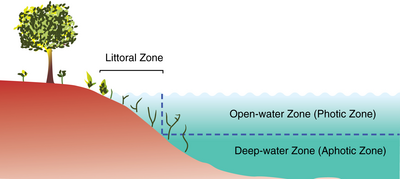

[3][7] Lakes are divided into photic and aphotic regions, the prior receiving sunlight and latter being below the depths of light penetration, making it void of photosynthetic capacity.

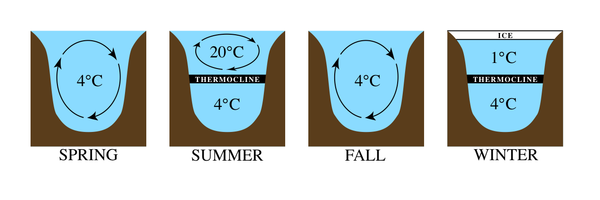

In temperate regions, for example, as air temperatures increase, the icy layer formed on the surface of the lake breaks up, leaving the water at approximately 4 °C.

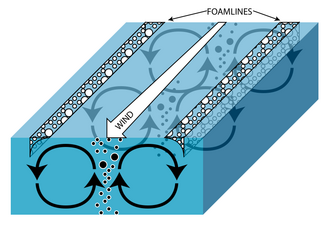

[2][3] This turbulence circulates nutrients in the water column, making it crucial for many pelagic species, however its effect on benthic and profundal organisms is minimal to non-existent, respectively.

[3] The degree of nutrient circulation is system specific, as it depends upon such factors as wind strength and duration, as well as lake or pool depth and productivity.

[1] In shallow, plant-rich pools there may be great fluctuations of oxygen, with extremely high concentrations occurring during the day due to photosynthesis and very low values at night when respiration is the dominant process of primary producers.

[2] Sediments are generally richer in phosphorus than lake water, however, indicating that this nutrient may have a long residency time there before it is remineralized and re-introduced to the system.

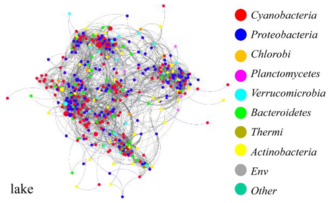

Free-living forms are associated with decomposing organic material, biofilm on the surfaces of rocks and plants, suspended in the water column, and in the sediments of the benthic and profundal zones.

To combat this, phytoplankton have developed density-changing mechanisms, by forming vacuoles and gas vesicles, or by changing their shapes to induce drag, thus slowing their descent.

[9] A very sophisticated adaptation utilized by a small number of species is a tail-like flagellum that can adjust vertical position, and allow movement in any direction.

Like phytoplankton, these species have developed mechanisms that keep them from sinking to deeper waters, including drag-inducing body forms, and the active flicking of appendages (such as antennae or spines).

In response, some species, especially Daphnia sp., make daily vertical migrations in the water column by passively sinking to the darker lower depths during the day, and actively moving towards the surface during the night.

These resting eggs have a diapause, or dormancy period, that should allow the zooplankton to encounter conditions that are more favorable to survival when they finally hatch.

[11] The invertebrates that inhabit the benthic zone are numerically dominated by small species, and are species-rich compared to the zooplankton of the open water.

The structurally diverse macrophyte beds are important sites for the accumulation of organic matter, and provide an ideal area for colonization.

[12] This autochthonous process involves the combination of carbon dioxide, water, and solar energy to produce carbohydrates and dissolved oxygen.

In the pelagic zone, dead fish and the occasional allochthonous input of litterfall are examples of coarse particulate organic matter (CPOM>1 mm).

Elements other than carbon, particularly phosphorus and nitrogen, are regenerated when protozoa feed on bacterial prey [15] and this way, nutrients become once more available for use in the water column.

[2] The decomposition of organic materials can continue in the benthic and profundal zones if the matter falls through the water column before being completely digested by the pelagic bacteria.

[2][17] The profundal zone is home to a unique group of filter feeders that use small body movements to draw a current through burrows that they have created in the sediment.

[17] Fish size, mobility, and sensory capabilities allow them to exploit a broad prey base, covering multiple zonation regions.

[19] Additional factors, including temperature regime, pH, nutrient availability, habitat complexity, speciation rates, competition, and predation, have been linked to the number of species present within systems.

[2][10] Phytoplankton and zooplankton communities in lake systems undergo seasonal succession in relation to nutrient availability, predation, and competition.

Sommer et al.[20] described these patterns as part of the Plankton Ecology Group (PEG) model, with 24 statements constructed from the analysis of numerous systems.

The following includes a subset of these statements, as explained by Brönmark and Hansson[2] illustrating succession through a single seasonal cycle: Winter 1.

A clear water phase occurs, as phytoplankton populations become depleted due to increased predation by growing numbers of zooplankton.

[2] There is a well-documented global pattern that correlates decreasing plant and animal diversity with increasing latitude, that is to say, there are fewer species as one moves towards the poles.

[21] This may be related to size, as Hillebrand and Azovsky[22] found that smaller organisms (protozoa and plankton) did not follow the expected trend strongly, while larger species (vertebrates) did.

[3] At a pH of 5–6 algal species diversity and biomass decrease considerably, leading to an increase in water transparency – a characteristic feature of acidified lakes.

[2][3] Acid rain has been especially harmful to lakes in Scandinavia, western Scotland, west Wales and the north eastern United States.