Surface tension

The net effect is the liquid behaves as if its surface were covered with a stretched elastic membrane.

This creates some internal pressure and forces liquid surfaces to contract to the minimum area.

[2] There is also a tension parallel to the surface at the liquid-air interface which will resist an external force, due to the cohesive nature of water molecules.

The balance between the cohesion of the liquid and its adhesion to the material of the container determines the degree of wetting, the contact angle, and the shape of meniscus.

Although easily deformed, droplets of water tend to be pulled into a spherical shape by the imbalance in cohesive forces of the surface layer.

The spherical shape minimizes the necessary "wall tension" of the surface layer according to Laplace's law.

Surface tension, represented by the symbol γ (alternatively σ or T), is measured in force per unit length.

where: The quantity in parentheses on the right hand side is in fact (twice) the mean curvature of the surface (depending on normalisation).

The table below shows how the internal pressure of a water droplet increases with decreasing radius.

Yet by fashioning the frame out of wire and dipping it in soap-solution, a locally minimal surface will appear in the resulting soap-film within seconds.

In the diagram, both the vertical and horizontal forces must cancel exactly at the contact point, known as equilibrium.

The vertical component of fla must exactly cancel the difference of the forces along the solid surface, fls − fsa.

Observe that in the special case of a water–silver interface where the contact angle is equal to 90°, the liquid–solid/solid–air surface tension difference is exactly zero.

That decrease is enough to compensate for the increased potential energy associated with lifting the fluid near the walls of the container.

where Pouring mercury onto a horizontal flat sheet of glass results in a puddle that has a perceptible thickness.

where In reality, the thicknesses of the puddles will be slightly less than what is predicted by the above formula because very few surfaces have a contact angle of 180° with any liquid.

The formula also predicts that when the contact angle is 0°, the liquid will spread out into a micro-thin layer over the surface.

This is due to a phenomenon called the Plateau–Rayleigh instability,[11] which is entirely a consequence of the effects of surface tension.

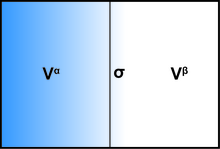

Gibbs developed the thermodynamic theory of capillarity based on the idea of surfaces of discontinuity.

[14] Gibbs considered the case of a sharp mathematical surface being placed somewhere within the microscopically fuzzy physical interface that exists between two homogeneous substances.

) and remained perfectly homogeneous right up to the mathematical boundary, without any surface effects, the total grand potential of this volume would be simply

As stated above, this implies the mechanical work needed to increase a surface area A is dW = γ dA, assuming the volumes on each side do not change.

Thermodynamics requires that for systems held at constant chemical potential and temperature, all spontaneous changes of state are accompanied by a decrease in this free energy

, that is, an increase in total entropy taking into account the possible movement of energy and particles from the surface into the surrounding fluids.

From this it is easy to understand why decreasing the surface area of a mass of liquid is always spontaneous, provided it is not coupled to any other energy changes.

van der Waals developed the theory of capillarity effects based on the hypothesis of a continuous variation of density.

[18][19] The van der Waals capillarity energy is now widely used in the phase field models of multiphase flows.

[20] The pressure inside an ideal spherical bubble can be derived from thermodynamic free energy considerations.

That is to say that when a liquid is forming small droplets, the equilibrium concentration of its vapor in its surroundings is greater.

[26] The effect can be viewed in terms of the average number of molecular neighbors of surface molecules (see diagram).