Landscape ecology

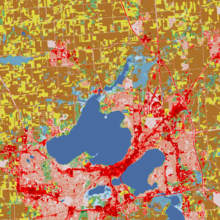

Landscapes are spatially heterogeneous geographic areas characterized by diverse interacting patches or ecosystems, ranging from relatively natural terrestrial and aquatic systems such as forests, grasslands, and lakes to human-dominated environments including agricultural and urban settings.

This includes studying the influence of pattern, or the internal order of a landscape, on process, or the continuous operation of functions of organisms.

This work considered the biodiversity on islands as the result of competing forces of colonization from a mainland stock and stochastic extinction.

This generalization spurred the growth of landscape ecology by providing conservation biologists a new tool to assess how habitat fragmentation affects population viability.

Recent growth of landscape ecology owes much to the development of geographic information systems (GIS)[14] and the availability of large-extent habitat data (e.g. remotely sensed datasets).

Landmark book publications defined the scope and goals of the discipline, including Naveh and Lieberman[16] and Forman and Godron.

[17][18] Forman[6] wrote that although study of "the ecology of spatial configuration at the human scale" was barely a decade old, there was strong potential for theory development and application of the conceptual framework.

[5] An example would be determining the amount of carbon present in the soil based on landform over a landscape, derived from GIS maps, vegetation types, and rainfall data for a region.

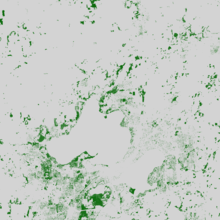

Remote sensing work has been used to extend landscape ecology to the field of predictive vegetation mapping, for instance by Janet Franklin.

For example:[19] Carl Troll conceives of landscape not as a mental construct but as an objectively given 'organic entity', a harmonic individuum of space.

John A. Wiens[24][25] opposes the traditional view expounded by Carl Troll, Isaak S. Zonneveld, Zev Naveh, Richard T. T. Forman/Michel Godron and others that landscapes are arenas in which humans interact with their environments on a kilometre-wide scale; instead, he defines 'landscape'—regardless of scale—as "the template on which spatial patterns influence ecological processes".

[37] Patch, a term fundamental to landscape ecology, is defined as a relatively homogeneous area that differs from its surroundings.

In a continuous landscape, such as a forest giving way to open woodland, the exact edge location is fuzzy and is sometimes determined by a local gradient exceeding a threshold, such as the point where the tree cover falls below thirty-five percent.

[38] An ecocline is another type of landscape boundary, but it is a gradual and continuous change in environmental conditions of an ecosystem or community.

[39] An ecotope is a spatial term representing the smallest ecologically distinct unit in mapping and classification of landscapes.

They are useful for the measurement and mapping of landscape structure, function, and change over time, and to examine the effects of disturbance and fragmentation.

An important consequence of repeated, random clearing (whether by natural disturbance or human activity) is that contiguous cover can break down into isolated patches.

[17] This principle is a major contribution to general ecological theories which highlight the importance of relationships among the various components of the landscape.

Integrity of landscape components helps maintain resistance to external threats, including development and land transformation by human activity.

[5] Analysis of land use change has included a strongly geographical approach which has led to the acceptance of the idea of multifunctional properties of landscapes.

[18] There are still calls for a more unified theory of landscape ecology due to differences in professional opinion among ecologists and its interdisciplinary approach (Bastian 2001).

Gradient analysis is another way to determine the vegetation structure across a landscape or to help delineate critical wetland habitat for conservation or mitigation purposes (Choesin and Boerner 2002).

[38] Research in northern regions has examined landscape ecological processes, such as the accumulation of snow, melting, freeze-thaw action, percolation, soil moisture variation, and temperature regimes through long-term measurements in Norway.

[43] The study analyzes gradients across space and time between ecosystems of the central high mountains to determine relationships between distribution patterns of animals in their environment.

Land change models are used in urban planning, geography, GIS, and other disciplines to gain a clear understanding of the course of a landscape.

Another recent development has been the more explicit consideration of spatial concepts and principles applied to the study of lakes, streams, and wetlands in the field of landscape limnology.

For example, a recent study assessed sustainable urbanization across Europe using evaluation indices, country-landscapes, and landscape ecology tools and methods.