Language acquisition

The capacity to successfully use language requires human beings to acquire a range of tools, including phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, and an extensive vocabulary.

Chomsky claimed the pattern is difficult to attribute to Skinner's idea of operant conditioning as the primary way that children acquire language.

Nativists such as Chomsky have focused on the hugely complex nature of human grammars, the finiteness and ambiguity of the input that children receive, and the relatively limited cognitive abilities of an infant.

Otherwise, they argue, it is extremely difficult to explain how children, within the first five years of life, routinely master the complex, largely tacit grammatical rules of their native language.

[citation needed] Emergentist theories, such as Brian MacWhinney's competition model, posit that language acquisition is a cognitive process that emerges from the interaction of biological pressures and the environment.

[31] On the other hand, cognitive-functional theorists use this anthropological data to show how human beings have evolved the capacity for grammar and syntax to meet our demand for linguistic symbols.

)[citation needed] Further, the generative theory has several constructs (such as movement, empty categories, complex underlying structures, and strict binary branching) that cannot possibly be acquired from any amount of linguistic input.

[citation needed] In recent years, the debate surrounding the nativist position has centered on whether the inborn capabilities are language-specific or domain-general, such as those that enable the infant to visually make sense of the world in terms of objects and actions.

[44] In a series of connectionist model simulations, Franklin Chang has demonstrated that such a domain general statistical learning mechanism could explain a wide range of language structure acquisition phenomena.

The central idea of these theories is that language development occurs through the incremental acquisition of meaningful chunks of elementary constituents, which can be words, phonemes, or syllables.

[52] The relational frame theory (RFT) (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes, Roche, 2001), provides a wholly selectionist/learning account of the origin and development of language competence and complexity.

RFT theorists introduced the concept of functional contextualism in language learning, which emphasizes the importance of predicting and influencing psychological events, such as thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, by focusing on manipulable variables in their own context.

RFT distinguishes itself from Skinner's work by identifying and defining a particular type of operant conditioning known as derived relational responding, a learning process that, to date, appears to occur only in humans possessing a capacity for language.

It is based largely on the socio-cultural theories of Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky, and was made prominent in the Western world by Jerome Bruner.

It differs substantially, though, in that it posits the existence of a social-cognitive model and other mental structures within children (a sharp contrast to the "black box" approach of classical behaviorism).

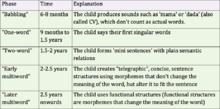

[15] A child will use short expressions such as Bye-bye Mummy or All-gone milk, which actually are combinations of individual nouns and an operator,[57] before they begin to produce gradually more complex sentences.

In the 1990s, within the principles and parameters framework, this hypothesis was extended into a maturation-based structure building model of child language regarding the acquisition of functional categories.

In terms of a merge-based theory of language acquisition,[61] complements and specifiers are simply notations for first-merge (= "complement-of" [head-complement]), and later second-merge (= "specifier-of" [specifier-head], with merge always forming to a head.

[63] As a consequence, at the "external/first-merge-only" stage, young children would show an inability to interpret readings from a given ordered pair, since they would only have access to the mental parsing of a non-recursive set.

[64] In addition to word-order violations, other more ubiquitous results of a first-merge stage would show that children's initial utterances lack the recursive properties of inflectional morphology, yielding a strict Non-inflectional stage-1, consistent with an incremental Structure-building model of child language.

[dubious – discuss][67][68] Yet, barring situations of medical abnormality or extreme privation, all children in a given speech-community converge on very much the same grammar by the age of about five years.

[69][70] Considerations such as those have led Chomsky, Jerry Fodor, Eric Lenneberg and others to argue that the types of grammar the child needs to consider must be narrowly constrained by human biology (the nativist position).

Research on the acquisition of the Romance and Scandinavian languages used aspects of the comparative method, but did not produce detailed comparisons across different levels of grammar.

Some researchers in the field of developmental neuroscience argue that fetal auditory learning mechanisms result solely from discrimination of prosodic elements.

This ability to sequence specific vowels gives newborn infants some of the fundamental mechanisms needed in order to learn the complex organization of a language.

From a neuroscientific perspective, neural correlates have been found that demonstrate human fetal learning of speech-like auditory stimuli that most other studies have been analyzing[clarification needed] (Partanen et al., 2013).

If a child knows fifty or fewer words by the age of 24 months, he or she is classified as a late-talker, and future language development, like vocabulary expansion and the organization of grammar, is likely to be slower and stunted.

For instance, a child may broaden the use of mummy and dada in order to indicate anything that belongs to its mother or father, or perhaps every person who resembles its own parents; another example might be to say rain while meaning I don't want to go out.

Some evidence suggests that speech processing occurs at a more rapid pace in some prelingually deaf children with cochlear implants than those with traditional hearing aids.

In June 2024, a cross-sectional study that the notable academic journal Scientific Reports published cautioned that "children with CIs exhibit significant variability in speech and language development": both "with too many recipients demonstrating suboptimal outcomes" and also with the investigations of those individuals broadly being "not well defined for prelingually deafened children with CIs, for whom language development is ongoing."