Languages of Italy

Some local languages do not stem from Latin, however, but belong to other Indo-European branches, such as Cimbrian (Germanic), Arbëresh (Albanian), Slavomolisano (Slavic) and Griko (Greek).

Of the indigenous languages, twelve are officially recognized as spoken by linguistic minorities:[7] Albanian,[8][9] Catalan, German, Greek, Slovene, Croatian, French, Franco-Provençal, Friulian, Ladin, Occitan and Sardinian;[7] at the present moment, Sardinian is regarded as the largest of such groups, with approximately one million speakers, even though the Sardophone community is overall declining.

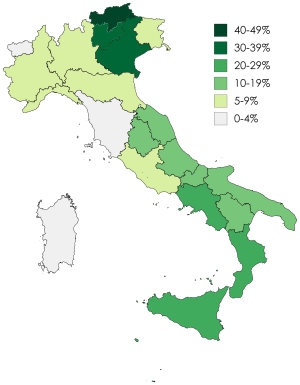

[10][11][12][13][14][15] However, full bilingualism (bilinguismo perfetto) is legally granted only to the three national minorities whose mother tongue is German, Slovene or French, and enacted in the regions of Trentino-Alto Adige, Friuli-Venezia Giulia and the Aosta Valley, respectively.

[24] Italian was first declared to be Italy's official language during the Fascist period, more specifically through the R.D.l., adopted on 15 October 1925, with the name of Sull'Obbligo della lingua italiana in tutti gli uffici giudiziari del Regno, salvo le eccezioni stabilite nei trattati internazionali per la città di Fiume.

Since the constitution was penned, there have been some laws and articles written on the procedures of criminal cases passed that explicitly state that Italian should be used: The Republic safeguards linguistic minorities by means of appropriate measures.Art.

[29][30][31] Since 1934, Minister Francesco Ercole had excluded in fact from the school curriculum any language other than Italian, in accordance with the policy of linguistic nationalism.

[7] According to the linguist Tullio De Mauro, the Italian delay of over 50 years in implementing Article 6 was caused by "decades of hostility to multilingualism" and "opaque ignorance".

The nominated people were Tullio de Mauro, Giovan Battista Pellegrini and Alessandro Pizzorusso, three notable figures who distinguished themselves with their life-long activity of research in the field of both linguistics and legal theory.

Based on linguistic, historical as well as anthropological considerations, the experts eventually selected thirteen groups, corresponding to the currently recognized twelve with the further addition of the Sinti and Romani-speaking populations.

The bill was met with resistance by all the subsequent legislatures, being reluctant to challenge the widely-held myth of "Italian linguistic homogeneity",[34] and only in 1999 did it eventually pass, becoming a law.

[44] In fact, the discrimination lay in the urgent need to award the highest degree of protection only to the French-speaking minority in the Aosta Valley and the German one in South Tyrol, owing to international treaties.

[46] A bill proposed by former prime minister Mario Monti's cabinet formally introduced a differential treatment between the twelve historical linguistic minorities, distinguishing between those with a "foreign mother tongue" (the groups protected by agreements with Austria, France and Slovenia) and those with a "peculiar dialect" (all the others).

[49] The Charter does not, however, establish at what point differences in expression result in a separate language, deeming it an "often controversial issue", and citing the necessity to take into account, other than purely linguistic criteria, also "psychological, sociological and political considerations".

The following five linguistic areas can be identified:[76] The following classification is proposed by Maiden:[78] The Northern Italian languages are conventionally defined as those Romance languages spoken north of the La Spezia–Rimini Line, which runs through the northern Apennine Mountains just to the north of Tuscany; however, the dialects of Occitan and Franco-Provençal spoken in the extreme northwest of Italy (e.g. the Valdôtain in the Aosta Valley) are generally excluded.