Lapis Niger

It is constructed on top of a sacred spot consisting of much older artifacts found about 5 ft (1.5 m) below the present ground level.

Located in the Comitium in front of the Curia Julia, this structure survived for centuries due to a combination of reverential treatment and overbuilding during the era of the early Roman Empire.

The earliest writings referring to this spot regard it as a suggestum where the early kings of Rome would speak to the crowds at the forum and to the Senate.

The Lapis Niger is mentioned in an uncertain and ambiguous way by several writers of the early Imperial period: Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Plutarch, and Festus.

An awning now protects the ancient relics until the covering is repaired, allowing the public to view the original suggestum for the first time in 50 years.

The antiquarian Verrius Flaccus (whose work is preserved only in the epitome of Pompeius Festus), a contemporary of Augustus, described a statue of a resting lion placed on each base, "just as they may be seen today guarding graves".

Archaeological excavations (1899–1905) revealed various dedicatory items from vase fragments, statues and pieces of animal sacrifices around at the site in a layer of deliberately placed gravel.

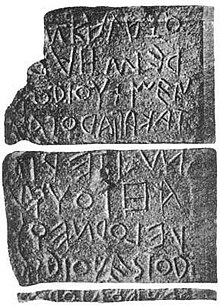

(or qvoi hoi...) sakros:es/ed:sord... ...[..]a[..]as/recei: ic (or io) ...evam/qvos: re... ...m:kalato/rem: hab (or hal) ...tod:iovxmen/ta: kapia:duo:tavr... m: iter[..]... ...m:qvoiha/velod: neqv...

Dumézil's attempt[5] is based on the assumption of a parallelism of some points of the fragmentary text inscribed on the monument and a passage of Cicero's De Divinatione (II 36.

[6] 'They' here denotes the calatores, public slaves whom the augurs and other sacerdotes (priests) had at their service, and who, in the quoted passage, are to execute orders aimed at preventing profane people from spoiling and, by their inadvertent action thereby rendering void, the sacred operation.

Varro in explaining the meaning of the name of the Via Sacra, states that the augurs, advancing along this street after leaving the arx used to inaugurate.

The remaining lines could also be interpreted similarly, in Dumézil's view: iustum and liquidum are technical terms used as qualifying auspices, meaning regular, correctly taken and favourable.

[12] Moreover, the original form of classic Latin aluus, 'abdomen', and also stools, as still attested in Cato Maior was *aulos, that Max Niedermann on the grounds of Lithuanian reconstructs as * au(e)los.

Dumézil then proposes the following interpretation for lines 12–16: ... ne, descensa tunc iunctorum iumentoru]m cui aluo, nequ[eatur (religious operation under course in the passive infinitive) auspici]o iusto liquido.

As for loi(u)quod, it may be an archaic form of a type of which one can cite other instances, as lucidus and Lucius, fluuidus and flŭuius, liuidus and Līuius.

Michael Grant, in his book Roman Forum writes: "The inscription found beneath the black marble ... clearly represents a piece of ritual law ... the opening words are translatable as a warning that a man who damages, defiles or violates the spot will be cursed.

One reconstruction of the text interprets it as referring to the misfortune which could be caused if two yoked draught cattle should happen while passing by to drop excrement simultaneously.

[14] Palmer instead, on the basis of a detailed analysis of every recognisable word, gave the following interpretation of this inscription, which he too considers to be a law: Whosoever (will violate) this (grove), let him be cursed.