Surname

English surnames began to be formed with reference to a certain aspect of that individual, such as their trade, father's name, location of birth, or physical features, and were not necessarily inherited.

850 AD) was known by the nisbah "al-'Ibadi", a federation of Arab Christian tribes that lived in Mesopotamia prior to the advent of Islam.

For example, Alexander the Great was known as Heracleides, as a supposed descendant of Heracles, and by the dynastic name Karanos/Caranus, which referred to the founder of the dynasty to which he belonged.

They would not significantly reappear again in Eastern Roman society until the 10th century, apparently influenced by the familial affiliations of the Armenian military aristocracy.

Other sources of surnames are personal appearance or habit, e.g. Delgado ("thin") and Moreno ("dark"); geographic location or ethnicity, e.g. Alemán ("German"); and occupations, e.g. Molinero ("miller"), Zapatero ("shoe-maker") and Guerrero ("warrior"), although occupational names are much more often found in a shortened form referring to the trade itself, e.g. Molina ("mill"), Guerra ("war"), or Zapata (archaic form of zapato, "shoe").

[16] In England the introduction of family names is generally attributed to the preparation of the Domesday Book in 1086, following the Norman Conquest.

[17] A four-year study led by the University of the West of England, which concluded in 2016, analysed sources dating from the 11th to the 19th century to explain the origins of the surnames in the British Isles.

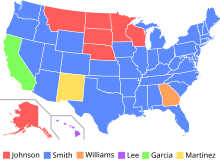

[18] The study found that over 90% of the 45,602 surnames in the dictionary are native to Britain and Ireland, with the most common in the UK being Smith, Jones, Williams, Brown, Taylor, Davies, and Wilson.

[19] The findings have been published in the Oxford English Dictionary of Family Names in Britain and Ireland, with project leader Richard Coates calling the study "more detailed and accurate" than those before.

[21] During the modern era many cultures around the world adopted family names, particularly for administrative reasons, especially during the age of European expansion and particularly since 1600.

[26] After arriving in the United States, European Jews who fled Nazi persecution sometimes anglicized their surnames to avoid discrimination.

Some such children were given surnames that reflected their condition, like (Italian) Esposito, Innocenti, Della Casagrande, Trovato, Abbandonata, or (Dutch) Vondeling, Verlaeten, Bijstand.

This is thought to be due to the tendency in Europe during the Middle Ages for migration to chiefly be from smaller communities to the cities and the need for new arrivals to choose a defining surname.

The latter is often called the Eastern naming order because Europeans are most familiar with the examples from the East Asian cultural sphere, specifically, Greater China, Korea (both North and South), Japan, and Vietnam.

In Telugu-speaking families in south India, surname is placed before personal / first name and in most cases it is only shown as an initial (for example 'S.'

[56][57] In France, Italy, Spain, Belgium and Latin America, administrative usage is to put the surname before the first on official documents.

Some Slavic cultures originally distinguished the surnames of married and unmarried women by different suffixes, but this distinction is no longer widely observed.

Wends or Lusatians), Sorbian used different female forms for unmarried daughters (Jordanojc, Nowcyc, Kubašec, Markulic), and for wives (Nowakowa, Budarka, Nowcyna, Markulina).

These suffixes are also used for foreign names, exclusively for grammar; Welby, the surname of the present Archbishop of Canterbury for example, becomes Velbis in Lithuanian, while his wife is Velbienė, and his unmarried daughter, Velbaitė.

[citation needed] King Henry VIII of England (reigned 1509–1547) ordered that marital births be recorded under the surname of the father.

[citation needed] The United States followed the naming customs and practices of English common law and traditions until recent times.

Beginning in the latter half of the 20th century, traditional naming practices (writes one commentator) were recognized as "com[ing] into conflict with current sensitivities about children's and women's rights".

[74] It is rare but not unknown for an English-speaking man to take his wife's family name, whether for personal reasons or as a matter of tradition (such as among matrilineal Canadian aboriginal groups, such as the Haida and Gitxsan).

Upon marriage to a woman, men in the United States can change their surnames to that of their wives, or adopt a combination of both names with the federal government, through the Social Security Administration.

[87][88] In Spain, especially Catalonia, the paternal and maternal surnames are often combined using the conjunction y ("and" in Spanish) or i ("and" in Catalan), see for example the economist Xavier Sala-i-Martin or painter Salvador Dalí i Domènech.

This custom, begun in medieval times, is decaying and only has legal validity [citation needed] in Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Nicaragua, Honduras, Peru, Panama, and to a certain extent in Mexico (where it is optional but becoming obsolete), but is frowned upon by people in Spain, Cuba, and elsewhere.

[citation needed] Some Hispanic people, after leaving their country, drop their maternal surname, even if not formally, so as to better fit into the non-Hispanic society they live or work in.

[citation needed] In many places, such as villages in Catalonia, Galicia, and Asturias and in Cuba, people are often informally known by the name of their dwelling or collective family nickname rather than by their surnames.

Some common nicknames are "Rubiu" (blond or red hair), "Roju" (reddish, referring to their red hair), "Chiqui" (small), "Jinchu" (big), and a bunch of names about certain characteristics, family relationship or geographical origin (pasiegu, masoniegu, sobanu, llebaniegu, tresmeranu, pejinu, naveru, merachu, tresneru, troule, mallavia, marotias, llamoso, lipa, ñecu, tarugu, trapajeru, lichón, andarível).

From the 1960s onwards, this usage spread to the common people, again under French influence, this time, however, due to the forceful legal adoption of their husbands' surname which was imposed onto Portuguese immigrant women in France.