Lattice (order)

It consists of a partially ordered set in which every pair of elements has a unique supremum (also called a least upper bound or join) and a unique infimum (also called a greatest lower bound or meet).

A lattice can be defined either order-theoretically as a partially ordered set, or as an algebraic structure.

With additional assumptions, further conclusions may be possible; see Completeness (order theory) for more discussion of this subject.

That article also discusses how one may rephrase the above definition in terms of the existence of suitable Galois connections between related partially ordered sets—an approach of special interest for the category theoretic approach to lattices, and for formal concept analysis.

In addition to this extrinsic definition as a subset of some other algebraic structure (a lattice), a partial lattice can also be intrinsically defined as a set with two partial binary operations satisfying certain axioms.

The absorption laws can be viewed as a requirement that the meet and join semilattices define the same partial order.

Since the commutative, associative and absorption laws can easily be verified for these operations, they make

introduced in this way defines a partial ordering within which binary meets and joins are given through the original operations

Furthermore, every non-empty finite lattice is bounded, by taking the join (respectively, meet) of all elements, denoted by

A bounded lattice can also be thought of as a commutative rig without the distributive axiom.

By commutativity, associativity and idempotence one can think of join and meet as operations on non-empty finite sets, rather than on pairs of elements.

In a bounded lattice the join and meet of the empty set can also be defined (as

The appropriate notion of a morphism between two lattices flows easily from the above algebraic definition.

In the order-theoretic formulation, these conditions just state that a homomorphism of lattices is a function preserving binary meets and joins.

Any homomorphism of lattices is necessarily monotone with respect to the associated ordering relation; see Limit preserving function.

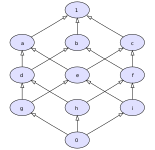

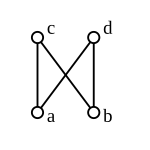

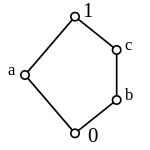

The converse is not true: monotonicity by no means implies the required preservation of meets and joins (see Pic.

We now introduce a number of important properties that lead to interesting special classes of lattices.

A poset is called a complete lattice if all its subsets have both a join and a meet.

While bounded lattice homomorphisms in general preserve only finite joins and meets, complete lattice homomorphisms are required to preserve arbitrary joins and meets.

Such lattices provide the most direct generalization of the completeness axiom of the real numbers.

[4][5] Since lattices come with two binary operations, it is natural to ask whether one of them distributes over the other, that is, whether one or the other of the following dual laws holds for every three elements

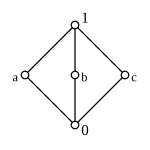

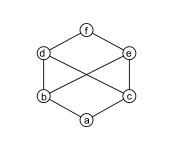

The only non-distributive lattices with fewer than 6 elements are called M3 and N5;[6] they are shown in Pictures 10 and 11, respectively.

The set of first-order terms with the ordering "is more specific than" is a non-modular lattice used in automated reasoning.

For a graded lattice, (upper) semimodularity is equivalent to the following condition on the rank function

For example, continuous lattices can be characterized as algebraic structures (with infinitary operations) satisfying certain identities.

While such a characterization is not known for algebraic lattices, they can be described "syntactically" via Scott information systems.

called complementation, introduces an analogue of logical negation into lattice theory.

Heyting algebras are an example of distributive lattices where some members might be lacking complements.

is called: However, many sources and mathematical communities use the term "atomic" to mean "atomistic" as defined above.

Note that in many applications the sets are only partial lattices: not every pair of elements has a meet or join.

The labelled elements also violate the distributivity equation but satisfy its dual