Law of France

[11][3] As such, the binding circulaires règlementaires are reviewed like other administrative acts, and can be found illegal if they contravene a parliamentary statute.

[24][5] French judicial decisions, especially in its highest courts, are written in a highly laconic and formalist style, incomprehensible to non-lawyers.

[27] This has led scholars to criticize the courts for being overly formalistic and even disingenuous, for maintaining the facade of judges only interpreting legal rules and arriving at deductive results.

[28] In theory, codes should go beyond the compilation of discrete statues, and instead state the law in a coherent and comprehensive piece of legislation, sometimes introducing major reforms or starting anew.

[30] Historians tend to be attracted by the large regional or urban customs, rather than local judicial norms and practices.

[30] Beginning in the 12th century, Roman law emerged as a scholarly discipline, initially with professors from Bologna starting to teach the Justinian Code in southern France[31] and in Paris.

[32] Historians now tend to think that Roman law was more influential on the customs of southern France due to its medieval revival.

[33][32] In the North, private and unofficial compilations of local customs in different regions began to emerge in the 13th and 14th centuries.

[32] After the Hundred Years War, French kings began to assert authority over the kingdom in a quest of institutional centralization.

[32] Through the creation of a centralized absolute monarchy, an administrative and judicial system under the king also emerged by the second half of the fifteenth century.

[32] The Ordinance of Montils-les-Tours (1454) [fr] was an important juncture in this period, as it ordered the official recording and homologation of customary law.

[32] At the time, the wholesale adoption of Roman law and the ius commune would be unrealistic, as the king’s authority was insufficient to impose a unified legal system in all French provinces.

[32][34] Jean-Baptiste Colbert, the Minister of Finance and later also Secretary of the Navy in charge of the colonial empire and trade, was main architect of the codes.

[32] Ordinances would later be drawn up on Donations (1731), Wills (1735), Falsifications (1737), and Trustees (1747), but a unified code of private law would not be passed until 1804, under Napoleon and after the French Revolution.

[37][32] Judges sided with the local parliaments (judicial bodies in France) and the landed aristocracy, undermining royal authority and legislation.

[28][5] In addition, they introduced many classically liberal reforms, such as abolishing remaining feudal institutions and establishing rights of personality, property and contract for all male French citizens.

The major private law codes include: France follows an inquisitorial model, where the judge leads the proceedings and the gathering of evidence, acting in the public interest to bring out the truth of a case.

[42] This is contrasted with the adversarial model often seen in common law countries, where parties in the case play a primary role in the judicial process.

[42] In French civil cases, one party has the burden of proof, according to law, but both sides and the judge together gather and provide evidence.

[42] The prosecutor (procureur) or, in some serious cases, the juge d’instruction then control or supervise the police investigation and decide whether to prosecute.

However, the most serious cases tried by the cour d’assises (a branch of the Court of Appeal) involve three judges and nine jurors who jointly determine the verdict and sentencing.

[56][57] Such acts include the President to launch nuclear tests, sever financial aid to Iraq, dissolve Parliament, award honors, or to grant amnesty.

[42] To begin a case, an individual only need to write a letter to describe his identity, the grounds of challenging the decision, and the relief sought, and provide a copy of the administrative action; legal arguments are unnecessary in the initial stage.

[42] Although merely being a taxpayer is insufficient, those affected in a "special, certain and direct" manner (including moral interests) will have standing.

[48] Judges are typically professional civil servants, mostly recruited through exams and trained at the École Nationale de la Magistrature.

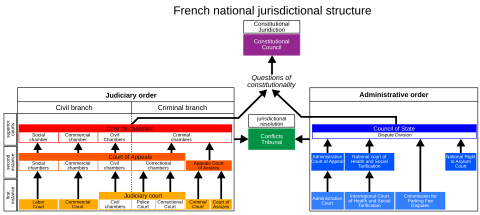

[48] The Council of State (Conseil d’État) is the highest court in administrative law and also the legal advisor of the executive branch.

[3] It originated from the King’s Privy Council, which adjudicated disputes with the state, which is exempt from other courts because of sovereign immunity.

[48] It also decides at first instance the validity of legislative or administrative decisions of the President, the Prime Minister, and certain senior civil servants.

A chambre mixte (a large panel of senior judges) or plenary session (Assemblée plénière) can convoke to resolve conflicts or hear important cases.

[48] The cour d’appel deals with questions of fact and law based on files from lower courts, and has the power to order additional investigations.