League of the Islanders

The last documents pertaining to the League date approximately to the second quarter of the century; no nēsiarchos is attested after c. 260 BC, and the number of Ptolemaic offerings to Delos also drops off sharply at the same time.

[3][6][9] It appears that when Ptolemaic control was first interrupted, after Ephesus, the Rhodians stepped into the power vacuum, concluding alliances with some of the islands like Ios.

[10] Ptolemaic control was possibly re-asserted to some degree after the end of the Second Syrian War, and a Ptolemaia festival was once again celebrated in 249 and 246 BC, but the evidence is meager.

At any rate, the Ptolemaic position collapsed completely after Andros, both as a result of the military losses as due to the lack of strategic interest: unlike earlier in the century, when the Cyclades had served as a springboard for interference in the Greek mainland, at this point the Ptolemies had more vital concerns in the Levant and Asia Minor to pursue.

Reger, however, considers that the available epigraphic and other evidence shows few indications of a Rhodian predominance, while the Macedonian kings seem to have limited their interest to the islands closest to the Greek mainland—Macedonian control is attested for Andros and possibly Keos and Kythnos, with some influence, probably temporary, in Amorgos and Paros in the direct aftermath of the Battle of Andros—and the panhellenic sanctuary at Delos.

In order to protect their political and commercial interests, such as the grain trade, where Rhodes held a dominant position, the Rhodians were active against pirates such as Demetrius of Pharos or the Cretan cities and the Aetolian League; both of the latter secretly sponsored by King Philip V of Macedon.

By c. 220 BC, according to Polybius (The Histories, IV.47.1), the Rhodians "were considered the supreme authority in maritime matters" and were called upon by merchants to intervene in cases such as the imposition of tolls by the Byzantines on passage of ships through the Bosporus.

[15][16] The motivations for Rhodes' move are unclear, but the historian Kenneth Sheedy has suggested that they stemmed at least partly from a desire to preempt other powers, whether the Kingdom of Pergamon or the Roman Republic, from establishing control over the area.

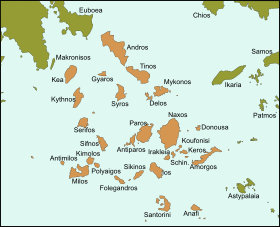

[3] The exact membership of the League can not be determined with accuracy, but it certainly comprised Mykonos, Kythnos, Keos, and probably also Ios under Antigonus, while Naxos, Andros, Amorgos, and Paros are also attested under the Ptolemies.

[27] As the League's sole collective organ, the synedrion was a sort of legislative council with representatives (σύνεδροι, synedroi) appointed by the member states.

[26][27] The synedrion awarded honours and distinctions to benefactors, and levied both regular and extraordinary financial contributions (συντάξεις, syntaxeis or εἰσφοραί, eisphorai) for maintenance of the League's military and for the common festivals.

He wielded executive power and was responsible for carrying out the synedrion's decisions, collect the member states' contributions, command the League military, and safeguard shipping in the Aegean.