Leap year

[1] Since astronomical events and seasons do not repeat in a whole number of days, calendars having a constant number of days each year will unavoidably drift over time with respect to the event that the year is supposed to track, such as seasons.

In the Solar Hijri and Bahá'í calendars, a leap day is added when needed to ensure that the following year begins on the March equinox.

[2][3] For example, since 1 March was a Friday in 2024, it will be a Saturday in 2025, a Sunday in 2026, and a Monday in 2027, but will then "leap" over Tuesday to fall on a Wednesday in 2028.

The length of a day is also occasionally corrected by inserting a leap second into Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) because of variations in Earth's rotation period.

On 1 January 45 BC, by edict, Julius Caesar reformed the historic Roman calendar to make it a consistent solar calendar (rather than one which was neither strictly lunar nor strictly solar), thus removing the need for frequent intercalary months.

Prior to Caesar's creation of what would be the Julian calendar, February was already the shortest month of the year for Romans.

The Gregorian calendar was designed to keep the vernal equinox on or close to 21 March, so that the date of Easter (celebrated on the Sunday after the ecclesiastical full moon that falls on or after 21 March) remains close to the vernal equinox.

In a leap year in the original Julian calendar, there were indeed two days both numbered 24 February.

This practice continued for another fifteen to seventeen centuries, even after most countries had adopted the Gregorian calendar.

It was regarded as in force in the time of the famous lawyer Sir Edward Coke (1552–1634) because he cites it in his Institutes of the Lawes of England.

However, Coke merely quotes the Act with a short translation and does not give practical examples.

... and by (b) the statute de anno bissextili, it is provided, quod computentur dies ille excrescens et dies proxime præcedens pro unico dii, so as in computation that day excrescent is not accounted.

[14] It was not until the passage of the Calendar (New Style) Act 1750 that 29 February was formally recognised in British law.

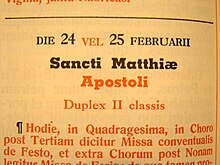

[26] Until 1970, the Roman Catholic Church always celebrated the feast of Saint Matthias on a. d. VI Kal.

This shift did not take place in pre-Reformation Norway and Iceland; Pope Alexander III ruled that either practice was lawful.

The feast of St. Matthias is celebrated in August, so leap years do not affect his commemoration, and, while the feast of the First and Second Findings of the Head of John the Baptist is celebrated on 24 February, the Orthodox church calculates days from the beginning of the current month, rather than counting down days to the Kalends of the following month, this is not affected.

In Ireland and Britain, it is a tradition that women may propose marriage only in leap years.

[28] Supposedly, a 1288 law by Queen Margaret of Scotland (then age five and living in Norway), required that fines be levied if a marriage proposal was refused by the man; compensation was deemed to be a pair of leather gloves, a single rose, £1, and a kiss.

[citation needed] According to Felten: "A play from the turn of the 17th century, 'The Maydes Metamorphosis,' has it that 'this is leape year/women wear breeches.'

A few hundred years later, breeches wouldn't do at all: Women looking to take advantage of their opportunity to pitch woo were expected to wear a scarlet petticoat – fair warning, if you will.

"[30] In Finland, the tradition is that if a man refuses a woman's proposal on leap day, he should buy her the fabrics for a skirt.

[31] In France, since 1980, a satirical newspaper titled La Bougie du Sapeur is published only on leap year, on 29 February.

[33] One in five engaged couples in Greece will plan to avoid getting married in a leap year.

[34] In February 1988 the town of Anthony, Texas, declared itself the "leap year capital of the world", and an international leapling birthday club was started.

This phenomenon may be exploited for dramatic effect when a person is declared to be only a quarter of their actual age, by counting their leap-year birthday anniversaries only.

This is a very good approximation to the mean tropical year, but because the vernal equinox year is slightly longer, the Revised Julian calendar, for the time being, does not do as good a job as the Gregorian calendar at keeping the vernal equinox on or close to 21 March.

These postponement rules reduce the number of different combinations of year length and starting days of the week from 28 to 14, and regulate the location of certain religious holidays in relation to the Sabbath.

A second reason is that Hoshana Rabbah, the 21st day of the Hebrew year, will never be on Saturday.

These rules for the Feasts do not apply to the years from the Creation to the deliverance of the Hebrews from Egypt under Moses.

13-month years follow the same pattern, with the addition of the 30-day Adar Alef, giving them between 383 and 385 days.