Lectio Divina

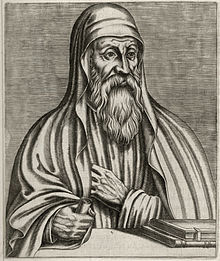

Before the beginning of the Western monastic communities, a key contribution to the foundation of Lectio Divina came from Origen in the 3rd century, with his view of "Scripture as a sacrament".

Origen taught that the reading of Scripture could help move beyond elementary thoughts and discover the higher wisdom hidden in the "Word of God".

[6] Origen's methods were then learned by Ambrose of Milan, who towards the end of the 4th century taught them to Saint Augustine, thereby introducing them into the monastic traditions of the Western Church thereafter.

These early communities gave rise to the tradition of a Christian life of "constant prayer" in a monastic setting.

[13] According to Jean Leclercq, OSB, the founders of the medieval tradition of Lectio Divina were Saint Benedict and Pope Gregory I.

A text that combines these traditions is Romans 10:8–10 where Apostle Paul refers to the presence of God's word in the believer's "mouth or heart".

[17] Early in the 12th century, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux was instrumental in re-emphasizing the importance of Lectio Divina within the Cistercian order.

Bernard considered Lectio Divina and contemplation guided by the Holy Spirit the keys to nourishing Christian spirituality.

[18] Seek in reading and you will find in meditation; knock in prayer and it will be opened to you in contemplation — The four stages of Lectio Divina as taught by John of the Cross.The progression from Bible reading, to meditation, to prayer, to loving regard for God, was first formally described by Guigo II, a Carthusian monk and prior of Grande Chartreuse who died late in the 12th century.

[3] Guigo II's book The Ladder of Monks is subtitled "a letter on the contemplative life" and is considered the first description of methodical prayer in the western mystical tradition.

The fourth stage is when the prayer, in turn, points to the gift of quiet stillness in the presence of God, called contemplation.

[23] In 1965, one of the principal documents of the Second Vatican Council, the dogmatic constitution Dei verbum ("Word of God") emphasized the use of Lectio Divina.

On the 40th anniversary of Dei verbum in 2005, Pope Benedict XVI reaffirmed its importance and stated: I would like in particular to recall and recommend the ancient tradition of Lectio Divina: the diligent reading of Sacred Scripture accompanied by prayer brings about that intimate dialogue in which the person reading hears God who is speaking, and in praying, responds to him with trusting openness of heart [cf.

[24]In his November 6, 2005 Angelus address, Benedict XVI emphasized the role of the Holy Spirit in Lectio Divina:[25] In his annual Lenten addresses to the priests of the Diocese of Rome, Pope Benedict – mainly after the 2008 Synod of Bishops on the Bible – emphasized Lectio Divina's importance, as in 2012, when he used Ephesians 4:1–16 on a speech about certain problems facing the Church.

"[2] An example would be sitting quietly and in silence and reciting a prayer inviting the Holy Spirit to guide the reading of the Scripture that is to follow.

[16] The biblical basis for the preparation goes back to 1 Corinthians 2:9–10 which emphasizes the role of the Holy Spirit in revealing the Word of God.

[2] The biblical basis for the reading goes back to Romans 10:8–10 and the presence of God's word in the believer's "mouth or heart".

Other theological analysis may follow, e.g. the cost at which Jesus the Lamb of God provided peace through his obedience to the will of the Father, etc.

[4] However, these theological analyses are generally avoided in Lectio Divina, where the focus is on Christ as the key that interprets the passage and relates it to the meditator.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church defines contemplative prayer as "the hearing the Word of God" in an attentive mode.

In the 12th century, Saint Bernard of Clairvaux compared the Holy Spirit to a kiss by the Eternal Father which allows the practitioner of contemplative prayer to experience union with God.

[36] From a theological perspective, God's grace is considered a principle, or cause, of contemplation, with its benefits delivered through the gifts of the Holy Spirit.

[39] It is likely that Teresa did not initially know of Guigo II's methods, although she may have been indirectly influenced by those teachings via the works of Francisco de Osuna which she studied in detail.