Lectionary

A lectionary (Latin: lectionarium) is a book or listing that contains a collection of scripture readings appointed for Christian or Jewish worship on a given day or occasion.

Typically, a lectionary will go through the scriptures in a logical pattern, and also include selections which were chosen by the religious community for their appropriateness to particular occasions.

[4] Within Christianity, the use of pre-assigned, scheduled readings from the scriptures can be traced back to the early church, and seems to have developed out of the practices of the second temple period.

The earliest documentary record of a special book of readings is a reference by Gennadius of Massilia to a work produced by Musaeus of Marseilles at the request of Bishop Venerius of Marseilles, who died in 452, though there are 3rd-century references to liturgical readers as a special role in the clergy.

The reason for these limited selections was to maintain consistency,[citation needed] as was a true feature in the Roman Rite.

After the Second Vatican Council of 1962–1965, the Holy See, even before producing an actual lectionary (in Latin), promulgated the Ordo Lectionum Missae (Order of the Readings for Mass), giving indications of the revised structure and the references to the passages chosen for inclusion in the new official lectionary of the Roman Rite of Mass.

This revised Mass Lectionary, covering much more of the Bible than the readings in the Tridentine Roman Missal, which recurred after a single year, has been translated into the many languages in which the Roman Rite Mass is now celebrated, incorporating existing or specially prepared translations of the Bible and with readings for national celebrations added either as an appendix or, in some cases, incorporated into the main part of the lectionary.

Like the Mass lectionary, they generally organize the readings for worship services on Sundays in a three-year cycle, with four elements on each Sunday, and three elements during daily Mass: The lectionaries (both Catholic and RCL versions) are organized into three-year cycles of readings.

The Gospel of John is read throughout Easter, and is used for other liturgical seasons including Advent, Christmas, and Lent where appropriate.

Other known witnesses of the Christian Jerusalem-Rite Lectionary are those preserved in Georgian, Caucasian Albanian language, and Armenian translations (6th to 8th centuries CE).

Those churches (Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic) which follow the Rite of Constantinople, provide an epistle and Gospel reading for most days of the year, to be read at the Divine Liturgy; however, during Great Lent there is no celebration of the liturgy on weekdays (Monday through Friday), so no epistle and Gospel are appointed for those days.

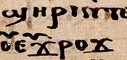

As a historical note, the Greek lectionaries are a primary source for the Byzantine text-type used in the scholarly field of textual criticism.

In the Byzantine practice, the readings are in the form of pericopes (selections from scripture containing only the portion actually chanted during the service), and are arranged according to the order in which they occur in the church year, beginning with the Sunday of Pascha (Easter), and continuing throughout the entire year, concluding with Holy Week.

The Lukan Jump is related to the chronological proximity of the Elevation of the Cross to the Conception of the Forerunner (St. John the Baptist), celebrated on 23 September.

The reasoning is theological and is based on a vision of Salvation History: the Conception of the Forerunner constitutes the first step of the New Economy, as mentioned in the stikhera of the matins of this feast.

If there is a weekday Liturgy celebrated on a non-feast day, the custom is to read the Pauline epistle only, followed by the Gospel.