Jurisprudence

From the early Roman Empire to the 3rd century, a relevant body of literature was produced by groups of scholars, including the Proculians and Sabinians.

It was during the Eastern Roman Empire (5th century) that legal studies were once again undertaken in depth, and it is from this cultural movement that Justinian's Corpus Juris Civilis was born.

Another approach to natural-law jurisprudence generally asserts that human law must be in response to compelling reasons for action.

[19] His longest discussion of his theory of justice occurs in Nicomachean Ethics and begins by asking what sort of mean a just act is.

[27] Thomas Aquinas is the foremost classical proponent of natural theology, and the father of the Thomistic school of philosophy, for a long time the primary philosophical approach of the Roman Catholic Church.

Francisco de Vitoria was perhaps the first to develop a theory of ius gentium (law of nations), and thus is an important figure in the transition to modernity.

Some scholars have upset the standard account of the origins of International law, which emphasises the seminal text De iure belli ac pacis by Hugo Grotius, and argued for Vitoria and, later, Suárez's importance as forerunners and, potentially, founders of the field.

[30] Others, such as Koskenniemi, have argued that none of these humanist and scholastic thinkers can be understood to have founded international law in the modern sense, instead placing its origins in the post-1870 period.

Writing after World War II, Lon L. Fuller defended a secular and procedural form of natural law.

[1] Analytic, or clarificatory, jurisprudence takes a neutral point of view and uses descriptive language when referring to various aspects of legal systems.

[34] David Hume argued, in A Treatise of Human Nature,[35] that people invariably slip from describing what the world is to asserting that we therefore ought to follow a particular course of action.

In Germany, Austria and France, the work of the "free law" theorists (e.g. Ernst Fuchs, Hermann Kantorowicz, Eugen Ehrlich and François Gény) encouraged the use of sociological insights in the development of legal and juristic theory.

The most internationally influential advocacy for a "sociological jurisprudence" occurred in the United States, where, throughout the first half of the twentieth century, Roscoe Pound, for many years the Dean of Harvard Law School, used this term to characterise his legal philosophy.

In the second half of the twentieth century, sociological jurisprudence as a distinct movement declined as jurisprudence came more strongly under the influence of analytical legal philosophy; but with increasing criticism of dominant orientations of legal philosophy in English-speaking countries in the present century, it has attracted renewed interest.

Exclusive legal positivists, notably Joseph Raz, go further than the standard thesis and deny that it is possible for morality to be a part of law at all.

In Leviathan, Hobbes argues that without an ordered society life would be "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short.

Austin explained the descriptive focus for legal positivism by saying, "The existence of law is one thing; its merit and demerit another.

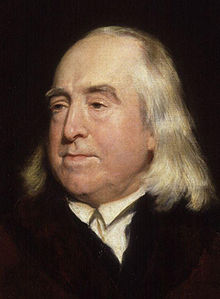

Along with Hume, Bentham was an early and staunch supporter of the utilitarian concept, and was an avid prison reformer, advocate for democracy, and firm atheist.

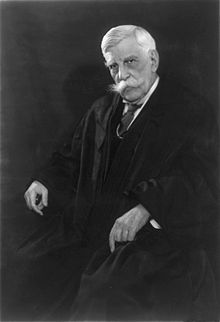

[45] H. L. A. Hart criticized Austin and Bentham's early legal positivism because the command theory failed to account for individual's compliance with the law.

Hans Kelsen is considered one of the preeminent jurists of the 20th century and has been highly influential in Europe and Latin America, although less so in common law countries.

In the English-speaking world, the most influential legal positivist of the twentieth century was H. L. A. Hart, professor of jurisprudence at Oxford University.

The validity of a legal system comes from the "rule of recognition", which is a customary practice of officials (especially barristers and judges) who identify certain acts and decisions as sources of law.

Joseph Raz's theory of legal positivism argues against the incorporation of moral values to explain law's validity.

"[50] Raz argues that law's authority is identifiable purely through social sources, without reference to moral reasoning.

[52] Some philosophers used to contend that positivism was the theory that held that there was "no necessary connection" between law and morality; but influential contemporary positivists—including Joseph Raz, John Gardner, and Leslie Green—reject that view.

Legal realism is the view that a theory of law should be descriptive and account for the reasons why judges decide cases as they do.

Karl Llewellyn, another founder of the U.S. legal realism movement, similarly believed that the law is little more than putty in the hands of judges who are able to shape the outcome of cases based on their personal values or policy choices.

John Stuart Mill was a pupil of Bentham's and was the torch bearer for utilitarian philosophy throughout the late nineteenth century.

[69] In contemporary legal theory, the utilitarian approach is frequently championed by scholars who work in the law and economics tradition.

Rawls argued from this "original position" that we would choose exactly the same political liberties for everyone, like freedom of speech, the right to vote, and so on.