Legendary horses of Pas-de-Calais

Ech goblin and the qu'vau blanc from Saint-Pol-sur-Ternoise, which wore a collar with bells to attract its victims, play the same role, as does ch'blanc qu'vo from Maisnil, or the animal from Vaudricourt, a white horse or gray donkey that carried off twenty children and eventually drowned them.

[citation needed] The Nord-Pas-de-Calais region abounds in legends, whether attached to trees, stones, mountains, ghosts, the devil, giants, saints or fantastic animals.

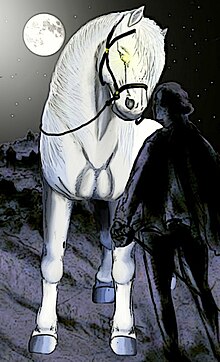

These legends share many common features in the vision of these pale horses, with their negative symbolism, their lengthening backs and all ending up rid of their riders, usually by throwing them into the water.

It is recorded by the Celtic Academy:"Finally, my dear friend, I went to visit the Tombelles, guided by a peasant woman who told me, without my asking, that this place was the cemetery of a foreign army that had occupied the area around Questreque a long time ago.

The Mont de Blanque-Jument, according to the tradition of the inhabitants of Samer, is so named because a white mare of perfect beauty, belonging to no master, was once seen on its summit, approaching passers-by and offering her rump to be ridden.

[11] Ch'blanc qu'vo is mentioned by elficologist Pierre Dubois in his Encyclopédie des fées as a fabulous horse specific to Maisnil, whose mane is trimmed with bells.

[12] Mlle Leroy reports in Henri Dontenville's La France mythologique that, according to a folklorist from Artesia, ch 'blanc qu'vose is confused with ech goblin "which was used to threaten unbearable children".

In his Evangiles du Diable, Claude Seignolle tells of a gray donkey that appeared in the square at Vaudricourt during midnight mass and obediently allowed itself to be ridden by the children fleeing the church, stretching out its back so that twenty of them could sit on it.

[14] Pierre Dubois mentions the same story in his Encyclopédie des fées, but this time it concerns a "magnificent white horse" that drowns its young riders in a bottomless pond, and disappears into a chasm after each of its reappearances on Christmas Day.

The story is often very similar, featuring a beautiful pale horse appearing in the middle of the night, who gently lets himself be ridden, before escaping the control of his rider(s).

[20] Many also see it as an archetype of the horses of death, the blanque mare sharing the same symbolism as the Bian cheval des Vosges or the German Schimmelreiter,[21][22] an animal of marine catastrophe that breaks dikes during storms, and of which it is a negative and sinister "close relative".

The Celtic Academy asserts that the blanque mare of Boulonnais is the manifestation of a spirit,[5] and Claude Seignolle likens the gray donkey of Vaudricourt to a transformation of the Devil into an animal.

[14] Édouard Brasey sees the blanque mare and the Schimmel Reiter as lutins or bogeymen charged with frightening disobedient children, as opposed to the Mallet horse, which is said to be a form of the Devil himself.

[27] The Japanese author Yanagida sees this as a ritual transformation of the horse into the liquid element, and notes that as far back as the Neolithic period, water genies have been associated with equines.