Chanson de geste

[12] Critics like Claude Charles Fauriel, François Raynouard and German Romanticists like Jacob Grimm posited the spontaneous creation of lyric poems by the people as a whole at the time of the historic battles, which were later put together to form the epics.

[13] This was the basis for the "cantilena" theory of epic origin, which was elaborated by Gaston Paris, although he maintained that single authors, rather than the multitude, were responsible for the songs.

[14] At the end of the 19th century, Pio Rajna, seeing similarities between the chansons de geste and old Germanic/Merovingian tales, posited a Germanic origin for the French poems.

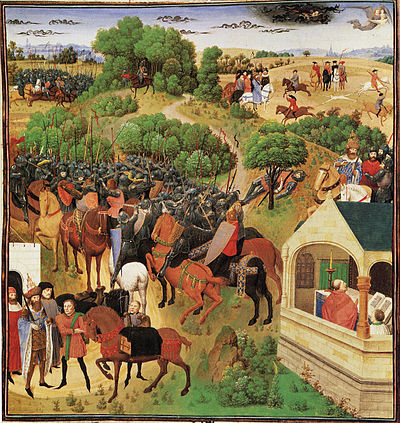

[19] Composed in Old French and apparently intended for oral performance by jongleurs, the chansons de geste narrate legendary incidents (sometimes based on real events) in the history of France during the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries, the age of Charles Martel, Charlemagne and Louis the Pious, with emphasis on their conflicts with the Moors and Saracens, and also disputes between kings and their vassals.

[20] A key theme of the chansons de geste, which set them off from the romances (which tended to explore the role of the "individual"), is their critique and celebration of community/collectivity (their epic heroes are portrayed as figures in the destiny of the nation and Christianity)[21] and their representation of the complexities of feudal relations and service.

[3] Other fantasy and adventure elements, derived from the romances, were gradually added:[3] giants, magic, and monsters increasingly appear among the foes along with Muslims.

Desuz un pin, delez un eglanter Un faldestoed i unt, fait tout d'or mer: La siet li reis ki dulce France tient.

He carried away Brohadas, son of the Sultan of Persia, Who had been killed in the battle by the clean sword Of the brave-spirited good duke Godfrey Right in front of Antioch, down in the meadow.

Similarly, scholars differ greatly on the social condition and literacy of the poets themselves; were they cultured clerics or illiterate jongleurs working within an oral tradition?

As an indication of the role played by orality in the tradition of the chanson de geste, lines and sometimes whole stanzas, especially in the earlier examples, are noticeably formulaic in nature, making it possible both for the poet to construct a poem in performance and for the audience to grasp a new theme with ease.

Several manuscript texts include lines in which the jongleur demands attention, threatens to stop singing, promises to continue the next day, and asks for money or gifts.

By the middle of the 12th century, the corpus of works was being expanded principally by "cyclisation", that is to say by the formation of "cycles" of chansons attached to a character or group of characters—with new chansons being added to the ensemble by singing of the earlier or later adventures of the hero, of his youthful exploits ("enfances"), the great deeds of his ancestors or descendants, or his retreat from the world to a convent ("moniage") – or attached to an event (like the Crusades).

One can be found in the fabliau entitled Des Deux Bordeors Ribauz, a humorous tale of the second half of the 13th century, in which a jongleur lists the stories he knows.

These chansons deal with knights who were typically younger sons, not heirs, who seek land and glory through combat with the Infidel (in practice, Muslim) enemy.

This local cycle of epics of Lorraine traditional history, in the late form in which it is now known, includes details evidently drawn from Huon de Bordeaux and Ogier le Danois.

In medieval Germany, the chansons de geste elicited little interest from the German courtly audience, unlike the romances which were much appreciated.

While The Song of Roland was among the first French epics to be translated into German (by Konrad der Pfaffe as the Rolandslied, c.1170), and the German poet Wolfram von Eschenbach based his (incomplete) 13th century epic Willehalm (consisting of seventy-eight manuscripts) on the Aliscans, a work in the cycle of William of Orange (Eschenbach's work had a great success in Germany), these remained isolated examples.

Other than a few other works translated from the cycle of Charlemagne in the 13th century, the chansons de geste were not adapted into German, and it is believed that this was because the epic poems lacked what the romances specialized in portraying: scenes of idealized knighthood, love and courtly society.

In Italy, there exist several 14th-century texts in verse or prose which recount the feats of Charlemagne in Spain, including a chanson de geste in Franco-Venetian, the Entrée d'Espagne (c.1320)[65] (notable for transforming the character of Roland into a knight errant, similar to heroes from the Arthurian romances[66]), and a similar Italian epic La Spagna (1350–1360) in ottava rima.

The Welsh poet, painter, soldier and engraver David Jones's Modernist poem "In Parenthesis" was described by contemporary critic Herbert Read as having "the heroic ring which we associate with the old chansons de geste".