Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz

21 June] – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat who is credited, alongside Sir Isaac Newton, with the creation of calculus in addition to many other branches of mathematics, such as binary arithmetic and statistics.

Leibniz has been called the "last universal genius" due to his vast expertise across fields, which became a rarity after his lifetime with the coming of the Industrial Revolution and the spread of specialized labor.

Leibniz also made major contributions to physics and technology, and anticipated notions that surfaced much later in probability theory, biology, medicine, geology, psychology, linguistics and computer science.

The work of Leibniz anticipated modern logic and still influences contemporary analytic philosophy, such as its adopted use of the term "possible world" to define modal notions.

In December 1664 he published and defended a dissertation Specimen Quaestionum Philosophicarum ex Jure collectarum (An Essay of Collected Philosophical Problems of Right),[35] arguing for both a theoretical and a pedagogical relationship between philosophy and law.

[35][37] De Arte Combinatoria was inspired by Ramon Llull's Ars Magna and contained a proof of the existence of God, cast in geometrical form, and based on the argument from motion.

The main force in European geopolitics during Leibniz's adult life was the ambition of Louis XIV of France, backed by French military and economic might.

Leibniz proposed to protect German-speaking Europe by distracting Louis as follows: France would be invited to take Egypt as a stepping stone towards an eventual conquest of the Dutch East Indies.

Napoleon's failed invasion of Egypt in 1798 can be seen as an unwitting, late implementation of Leibniz's plan, after the Eastern hemisphere colonial supremacy in Europe had already passed from the Dutch to the British.

With Huygens as his mentor, he began a program of self-study that soon pushed him to making major contributions to both subjects, including discovering his version of the differential and integral calculus.

Leibniz managed to delay his arrival in Hanover until the end of 1676 after making one more short journey to London, where Newton accused him of having seen his unpublished work on calculus in advance.

The British Act of Settlement 1701 designated the Electress Sophia and her descent as the royal family of England, once both King William III and his sister-in-law and successor, Queen Anne, were dead.

The Elector Ernest Augustus commissioned Leibniz to write a history of the House of Brunswick, going back to the time of Charlemagne or earlier, hoping that the resulting book would advance his dynastic ambitions.

They never knew that he had in fact carried out a fair part of his assigned task: when the material Leibniz had written and collected for his history of the House of Brunswick was finally published in the 19th century, it filled three volumes.

A formal investigation by the Royal Society (in which Newton was an unacknowledged participant), undertaken in response to Leibniz's demand for a retraction, upheld Keill's charge.

Despite the intercession of the Princess of Wales, Caroline of Ansbach, George I forbade Leibniz to join him in London until he completed at least one volume of the history of the Brunswick family his father had commissioned nearly 30 years earlier.

Moreover, for George I to include Leibniz in his London court would have been deemed insulting to Newton, who was seen as having won the calculus priority dispute and whose standing in British official circles could not have been higher.

Leibniz was deeply interested in the new methods and conclusions of Descartes, Huygens, Newton, and Boyle, but the established philosophical ideas in which he was educated influenced his view of their work.

[134] Until the discovery of subatomic particles and the quantum mechanics governing them, many of Leibniz's speculative ideas about aspects of nature not reducible to statics and dynamics made little sense.

His vis viva was seen as rivaling the conservation of momentum championed by Newton in England and by Descartes and Voltaire in France; hence academics in those countries tended to neglect Leibniz's idea.

[140] In medicine, he exhorted the physicians of his time—with some results—to ground their theories in detailed comparative observations and verified experiments, and to distinguish firmly scientific and metaphysical points of view.

He also devised postulates and principles that apply to psychology: the continuum of the unnoticed petites perceptions to the distinct, self-aware apperception, and psychophysical parallelism from the point of view of causality and of purpose: "Souls act according to the laws of final causes, through aspirations, ends and means.

His characteristica universalis, calculus ratiocinator, and a "community of minds"—intended, among other things, to bring political and religious unity to Europe—can be seen as distant unwitting anticipations of artificial languages (e.g., Esperanto and its rivals), symbolic logic, even the World Wide Web.

[183] In the late 1660s the enlightened Prince-Bishop of Mainz Johann Philipp von Schönborn announced a review of the legal system and made available a position to support his current law commissioner.

Leibniz devoted considerable intellectual and diplomatic effort to what would now be called an ecumenical endeavor, seeking to reconcile the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches.

In this respect, he followed the example of his early patrons, Baron von Boyneburg and the Duke John Frederick—both cradle Lutherans who converted to Catholicism as adults—who did what they could to encourage the reunion of the two faiths, and who warmly welcomed such endeavors by others.

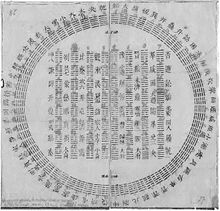

He noted how the I Ching hexagrams correspond to the binary numbers from 000000 to 111111, and concluded that this mapping was evidence of major Chinese accomplishments in the sort of philosophical mathematics he admired.

Hughes suggests that Leibniz's ideas of "simple substance" and "pre-established harmony" were directly influenced by Confucianism, pointing to the fact that they were conceived during the period when he was reading Confucius Sinarum Philosophus.

The amount, variety, and disorder of Leibniz's writings are a predictable result of a situation he described in a letter as follows: I cannot tell you how extraordinarily distracted and spread out I am.

Since then the branches in Potsdam, Münster, Hanover and Berlin have jointly published 57 volumes of the critical edition, with an average of 870 pages, and prepared index and concordance works.