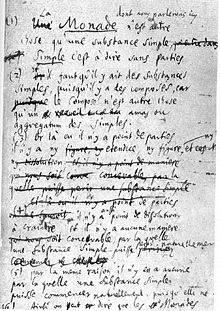

Monadology

During his last stay in Vienna from 1712 to September 1714, Leibniz wrote two short texts in French which were meant as concise expositions of his philosophy.

Christian Wolff and collaborators published translations in German and Latin of the second text which came to be known as The Monadology.

Without having seen the Dutch publication of the Principes they had assumed that it was the French original of the Monadology, which in fact remained unpublished until 1840.

The German translation appeared in 1720 as Lehrsätze über die Monadologie and the following year the Acta Eruditorum printed the Latin version as Principia philosophiae.

[2] Leibniz himself inserted references to the paragraphs of his Théodicée ("Theodicy", i.e. a justification of God), sending the interested reader there for more details.

This is the pre-established harmony which solved the mind-body problem, but at the cost of declaring any interaction between substances a mere appearance.

[5] Relying on the Greek etymology of the word entelechie (§18),[6] Leibniz posits quantitative differences in perfection between monads which leads to a hierarchical ordering.

The degree of perfection in each case corresponds to cognitive abilities and only spirits or reasonable animals are able to grasp the ideas of both the world and its creator.

(III) Composite substances or matter are "actually sub-divided without end" and have the properties of their infinitesimal parts (§65).

So it is with monads; they may seem to cause each other, but rather they are, in a sense, "wound" by God's pre-established harmony, and thus appear to be in synchronicity.

"In other words, in the Leibnizian monadology, simple substances are mind-like entities that do not, strictly speaking, exist in space but that represent the universe from a unique perspective.