Leishmania

L. aethiopica L. amazonensis L. arabica L. archibaldi (starus species) L. aristedesi (status disputed) L. (Viannia) braziliensis L. chagasi (syn.

Members of an ancient genus of Leishmania-like parasites, Paleoleishmania, have been detected in fossilized sand flies dating back to the early Cretaceous period.

Due to its broad and persistent prevalence throughout antiquity as a mysterious disease of diverse symptomatic outcomes, leishmaniasis has been dubbed with various names ranging from "white leprosy" to "black fever".

Some of these names suggest links to negative cultural beliefs or mythology, which still feed into the social stigmatization of leishmaniasis today.

[12] The causative parasite for the disease was identified in 1901 as a concurrent finding by William Boog Leishman and Charles Donovan.

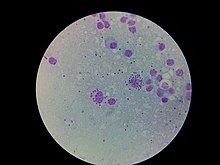

They independently visualised microscopic single-celled parasites (later called Leishman-Donovan bodies) living within the cells of infected human organs.

Leishmania species are unicellular eukaryotes having a well-defined nucleus and other cell organelles including kinetoplasts and flagella.

Depending on the stage of their life cycle, they exist in two structural variants, as:[14][15] The details of the evolution of this genus are debated, but Leishmania apparently evolved from an ancestral trypanosome lineage.

Trypanosoma cruzi groups with trypanosomes from bats, South American mammals, and kangaroos suggest an origin in the Southern Hemisphere.

The four genera Leptomonas, Crithidia, Leishmania, and Endotrypanum form the terminal branches, suggesting a relatively recent origin.

[21] Although it was suggested that Leishmania might have evolved in the Neotropics,[22] this is probably true for species belonging to the subgenera Viannia and Endotrypanum.

The division into the two subgenera (Leishmania and Viannia) was made by Lainson and Shaw in 1987 on the basis of their location within the insect gut.

Subgenus Viannia Lainson & Shaw 1987 The relationships between Leishmania and other genera such as Endotrypanum, Novymonas, Porcisia, and Zelonia is presently unclear as they are closely related.

[37] Transmitted by the sandfly, the protozoan parasites of L. major may switch the strategy of the first immune defense from eating/inflammation/killing to eating/no inflammation/no killing of their host phagocyte and corrupt it for their own benefit.

[citation needed] They use the willingly phagocytosing polymorphonuclear neutrophil granulocytes (PMNs) rigorously as a tricky hideout, where they proliferate unrecognized from the immune system and enter the long-lived macrophages to establish a "hidden" infection.

When the anti-inflammatory signal phosphatidylserine usually found on apoptotic cells, is exposed on the surface of dead parasites, L. major switches off the oxidative burst, thereby preventing killing and degradation of the viable pathogen.

The promastigote forms also release Leishmania chemotactic factor (LCF) to actively recruit neutrophils, but not other leukocytes, for instance monocytes or NK cells.

In addition to that, the production of interferon gamma (IFNγ)-inducible protein 10 (IP10) by PMNs is blocked in attendance of Leishmania, what involves the shut down of inflammatory and protective immune response by NK and Th1 cell recruitment.

[40] To save the integrity of the surrounding tissue from the toxic cell components and proteolytic enzymes contained in neutrophils, the apoptotic PMNs are silently cleared by macrophages.

Dying PMNs expose the "eat me"-signal phosphatidylserine which is transferred to the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane during apoptosis.

By reason of delayed apoptosis, the parasites that persist in PMNs are taken up into macrophages, employing an absolutely physiological and nonphlogistic process.

The strategy of this "silent phagocytosis" has the following advantages for the parasite: However, studies have shown this is unlikely, as the pathogens are seen to leave apoptopic cells and no evidence is known of macrophage uptake by this method.

Characteristics of intracellular digestion include an endosome fusing with a lysosome, releasing acid hydrolases which degrade DNA, RNA, proteins and carbohydrates.

The genomes of four Leishmania species (L. major, L. infantum, L. donovani and L. braziliensis) have been sequenced, revealing more than 8300 protein-coding and 900 RNA genes.

These clusters can be organized in head-to-head (divergent) or tail-to-tail (convergent) fashion, with the latter often separated by tRNA, rRNA and/or snRNA genes.

In addition, an experimental evolution study (EE Approach) was performed on L. donovani amastigotes obtained from clinical cases of hamsters.

An 11kb deletion was detected in the gene coding for Ld1S_360735700, a NIMA-related kinase with key functions in the correct progression of mitosis.

[42] A microbial pathogen's reproductive system is one of the basic biologic processes that condition the microorganism's ecology and disease spread.

[45] The rate of outcrossing between different strains of Leishmania in the sand fly vector depends on the frequency of co-infection.

Thus, meiotic events provide the adaptive advantage of efficient recombinational repair of DNA damages even when they do not lead to outcrossing[48]