Lemniscate elliptic functions

They were first studied by Giulio Fagnano in 1718 and later by Leonhard Euler and Carl Friedrich Gauss, among others.

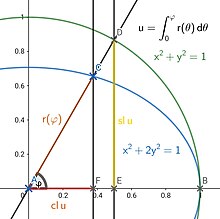

[1] The lemniscate sine and lemniscate cosine functions, usually written with the symbols sl and cl (sometimes the symbols sinlem and coslem or sin lemn and cos lemn are used instead),[2] are analogous to the trigonometric functions sine and cosine.

The lemniscate functions sl and cl can be defined as the solution to the initial value problem:[5] or equivalently as the inverses of an elliptic integral, the Schwarz–Christoffel map from the complex unit disk to a square with corners

[6] Beyond that square, the functions can be analytically continued to the whole complex plane by a series of reflections.

By comparison, the circular sine and cosine can be defined as the solution to the initial value problem: or as inverses of a map from the upper half-plane to a half-infinite strip with real part between

It has simple poles at Gaussian half-integer multiples of ϖ, complex numbers of the form

[15] There are also infinite series reflecting the distribution of the zeros and poles of sl:[16][17] The lemniscate functions satisfy a Pythagorean-like identity: As a result, the parametric equation

the argument sum and difference identities can be expressed as:[20] These resemble their trigonometric analogs: In particular, to compute the complex-valued functions in real components, Gauss discovered that where

is positive and odd,[26] then[27] which can be compared to the cyclotomic analog Just as for the trigonometric functions, values of the lemniscate functions can be computed for divisions of the lemniscate into n parts of equal length, using only basic arithmetic and square roots, if and only if n is of the form

is used solely for the purposes of this article; in references, notation for general Jacobi elliptic functions is used instead.

Analogously to the constructible polygons in the circle, the lemniscate can be divided into n sections of equal arc length using only straightedge and compass if and only if n is of the form

[35] Equivalently, the lemniscate can be divided into n sections of equal arc length using only straightedge and compass if and only if

The inverse lemniscate sine also describes the arc length s relative to the x coordinate of the rectangular elastica.

[36] This curve has y coordinate and arc length: The rectangular elastica solves a problem posed by Jacob Bernoulli, in 1691, to describe the shape of an idealized flexible rod fixed in a vertical orientation at the bottom end, and pulled down by a weight from the far end until it has been bent horizontal.

Bernoulli's proposed solution established Euler–Bernoulli beam theory, further developed by Euler in the 18th century.

Gauss showed that sl has the following product expansion, reflecting the distribution of its zeros and poles:[54] where Here,

Proof by logarithmic differentiation It can be easily seen (using uniform and absolute convergence arguments to justify interchanging of limiting operations) that (where

(this later turned out to be true) and commented that this “is most remarkable and a proof of this property promises the most serious increase in analysis”.

, such as and Thanks to a certain theorem[58] on splitting limits, we are allowed to multiply out the infinite products and collect like powers of

[73] The hyperbolic lemniscate sine (slh) and cosine (clh) can be defined as inverses of elliptic integrals as follows: where in

(sometimes called a squircle) the hyperbolic lemniscate sine and cosine are analogous to the tangent and cotangent functions in a unit circle

The length of the segment that runs perpendicularly from the intersection of this black diagonal with the red vertical axis to the point (1|0) should be called s. And the length of the section of the black diagonal from the coordinate origin point to the point of intersection of this diagonal with the cyan curved line of the superellipse has the following value depending on the slh value: This connection is described by the Pythagorean theorem.

In the case of the superellipse in the picture, half of the area concerned is shown in green.

The green area itself is created as the difference integral of the superellipse function from zero to the relevant height value minus the area of the adjacent triangle: The following transformation applies: And so, according to the chain rule, this derivation holds: This list shows the values of the Hyperbolic Lemniscate Sine accurately.

: These identities follow from the last-mentioned formula: Hence, their 4th powers again equal one, The following formulas for the lemniscatic sine and lemniscatic cosine are closely related: Analogous to the determination of the improper integral in the Gaussian bell curve function, the coordinate transformation of a general cylinder can be used to calculate the integral from 0 to the positive infinity in the function

This is the cylindrical coordinate transformation in the Gaussian bell curve function: And this is the analogous coordinate transformation for the lemniscatory case: In the last line of this elliptically analogous equation chain there is again the original Gauss bell curve integrated with the square function as the inner substitution according to the Chain rule of infinitesimal analytics (analysis).

In both cases, the determinant of the Jacobi matrix is multiplied to the original function in the integration domain.

In fact, the von Staudt–Clausen theorem determines the fractional part of the Bernoulli numbers: (sequence A000146 in the OEIS) where

[86] When lines of constant real or imaginary part are projected onto the complex plane via the hyperbolic lemniscate sine, and thence stereographically projected onto the sphere (see Riemann sphere), the resulting curves are spherical conics, the spherical analog of planar ellipses and hyperbolas.

A conformal map projection from the globe onto the 6 square faces of a cube can also be defined using the lemniscate functions.