Leninism

[1] The function of the Leninist vanguard party is to provide the working classes with the political consciousness (education and organisation) and revolutionary leadership necessary to depose capitalism.

As the vanguard party, the Bolsheviks viewed history through the theoretical framework of dialectical materialism, which sanctioned political commitment to the successful overthrow of capitalism, and then to instituting socialism; and, as the revolutionary national government, to realise the socio-economic transition by all means.

[7] In the early 20th century, the socio-economic backwardness of Imperial Russia (1721–1917) — characterized by combined and uneven economic development — facilitated rapid and intensive industrialisation, which produced a united, working-class proletariat in a predominantly agrarian society.

Moreover, because industrialisation was financed chiefly with foreign capital, Imperial Russia did not possess a revolutionary bourgeoisie with political and economic influence upon the workers and the peasants, as had been the case in the French Revolution (1789–1799) in the 18th century.

Such superexploitation allows wealthy countries to maintain a domestic labour aristocracy with a slightly higher standard of living than most workers, ensuring peaceful labour–capital relations in the capitalist homeland.

Despite being a guiding political influence, Lenin did not exercise absolute power and continually debated to have his points of view accepted as a course of revolutionary action.

In Bolshevik Russia, government by direct democracy was realised and effected by the soviets (elected councils of workers), which Lenin said was the "democratic dictatorship of the proletariat" postulated in orthodox Marxism.

"[3] In chapter five of The State and Revolution (1917), Lenin describes the dictatorship of the proletariat as: the organisation of the vanguard of the oppressed as the ruling class for the purpose of crushing the oppressors. ...

[18] In March 1921, the New Economic Policy (NEP, 1921–1929) allowed limited local capitalism (private commerce and internal free trade) and replaced grain requisitions with an agricultural tax managed by state banks.

The NEP was meant to resolve food-shortage riots by the peasantry and allowed limited private enterprise; the profit motive encouraged farmers to produce the crops required to feed town and country; and to economically re-establish the urban working class, who had lost many workers to fight the counter-revolutionary Civil War.

[21][22] The NEP nationalisation of the economy then would facilitate the industrialisation of Russia, politically strengthen the working class, and raise the standards of living for all Russians.

Lenin's socio-economic perspective was supported by the German Revolution of 1918–1919, the Italian insurrection and general strikes of 1920, and worker wage-riots in the UK, France, and the US.

[19][29][page needed] The counter-action against Stalin aligned with Lenin's advocacy of the right of self-determination for the national and ethnic groups of the deposed Tsarist Empire.

[36] After Lenin's death (21 January 1924), Trotsky ideologically battled the influence of Stalin, who formed ruling blocs within the Russian Communist Party (with Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, then with Nikolai Bukharin and then by himself) and so determined soviet government policy from 1924 onwards.

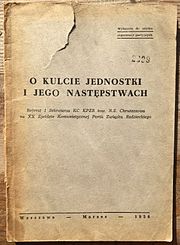

[43] The Trotskyist demands countered Stalin's political dominance of the Communist Party, which was officially characterised by the "cult of Lenin", the rejection of permanent revolution, and advocated the doctrine of socialism in one country.

In both cases, the Left Opposition denounced the regressive nature of Stalin's policy towards the wealthy kulak social class and the brutality of forced industrialisation.

[44] During the 1920s and the 1930s, Stalin fought and defeated the political influence of Trotsky and the Trotskyists in Russia using slander, antisemitism, censorship, expulsions, exile (internal and external), and imprisonment.

The anti-Trotsky campaign culminated in the executions (official and unofficial) of the Moscow Trials (1936–1938), which were part of the Great Purge of Old Bolsheviks who had led the Revolution.

[57] Historian Robert Vincent Daniels also viewed the Stalinist period as a counter-revolution in Soviet cultural life which revived patriotic propaganda, the Tsarist programme of Russification and traditional, military ranks which had been criticized by Lenin as expressions of "Great Russian chauvinism".

Trotsky also argued that he and Lenin had intended to lift the ban on the opposition parties such as the Mensheviks and Socialist Revolutionaries as soon as the economic and social conditions of Soviet Russia had improved.

[70] Other revisionist historians, such as Orlando Figes, whilst critical of the Soviet era, acknowledge that Lenin had actively sought to counter the growing influence of Stalin through a number of actions such as his alliance with Trotsky in 1922–23, opposition to Stalin on foreign trade, the Georgian affair and proposed party reforms which included the democratisation of the Central Committee and recruitment of 50–100 ordinary workers into the lower organs of the party.

Khrushchev contrasted this with the “despotism” of Stalin which require absolute submission to his position and he also highlighted that many of the people who were later annihilated as “enemies of the party", "had worked with Lenin during his life”.

[72] In his memoirs, Khrushchev argued that Stalin's widespread purges of the "most advanced nucleus of people" among the Old Bolsheviks and leading figures in the military and scientific fields had "undoubtedly" weakened the nation.

[73] Some Marxist theoreticians have disputed the view that the Stalinist dictatorship was a natural outgrowth of the Bolsheviks' actions as most of the original central committee members from 1917 were later eliminated by Stalin.

[74] George Novack stressed the initial efforts by the Bolsheviks to form a government with the Left Socialist Revolutionaries and bring other parties such as the Mensheviks into political legality.

[75] Tony Cliff argued the Bolshevik-Left Socialist Revolutionary coalition government dissolved the democratically elected Russian Constituent Assembly due to a number of reasons.

They cited the outdated voter-rolls which did not acknowledge the split among the Socialist Revolutionary party and the assemblies conflict with the Russian Congress of the Soviets as an alternative democratic structure.

[76] A similar analysis is present in more recent works such as those of Graeme Gill, who argues that "[Stalinism was] not a natural flow-on of earlier developments; [it formed a] sharp break resulting from conscious decisions by leading political actors."

"[77] Revisionist historians such as Sheila Fitzpatrick have criticized the focus on the upper levels of society and the use of Cold War concepts such as totalitarianism, obscuring the system's reality.

Proponents of left communism include Amadeo Bordiga, Herman Gorter, Paul Mattick, Sylvia Pankhurst, Antonie Pannekoek and Otto Rühle.